This beautiful piece puts me in mind of the story of why I started cooking with copper.

- Type: Tin-lined stewpot in hammered finish with brass handles fastened with three copper rivets; fitted lid with brass handle fastened with two copper rivets on each bracket

- French description: Bassine à ragoût étamée et martelée avec poignées en laiton munies de trois rivets en cuivre; couvercle emboîté avec poignée en laiton munie de deux rivets sur chaque support

- Dimensions: 34cm diameter by 18cm tall (13.4 inches by 7.1 inches)

- Thickness: 3mm at rim

- Weight: 8404g (18.5 lbs) without lid; 10694g (23.6 lbs) with lid

- Stampings: “H. POMMIER BRUXELLES”; “ML”; 34

- Maker and age estimate: H. Pommier; 1920-1940

- Source: lazylou2002 (eBay)

I’d like to start this post with a story about myself; click here if you’d rather skip to the discussion of this pot.

The story

A few years ago I was planning to host a family dinner party and I decided to make Marcella Hazan’s Bolognese sauce from her wonderful cookbook “The Essentials of Italian Cooking.” The focus of a Bolognese sauce is ground meat that has been infused with flavor over hours of simmering, and Marcella’s recipe accomplishes this by browning the meat and then adding and reducing first milk and then white wine. To this rich mixture are added the crushed tomatoes, and then begins the most important step: “Cook, uncovered, for 3 hours or more, stirring from time to time.” It’s the kind of recipe that fills the house with savory smells and I couldn’t imagine anything more wonderful to surprise and delight my guests.

On the appointed day I set to work with great eagerness. I had the perfect Staub enameled cast iron Dutch oven for the job, and I started early to allow for a six hour simmer to improve upon the minimum of three. Everything was going swimmingly until the step to set the sauce up for its long simmer: “When the tomatoes begin to bubble, turn the heat down so that the sauce cooks at the laziest of simmers, with just an intermittent bubble breaking through to the surface.”

I have a fancy but somewhat elderly Thermador gas cooktop. All its burners are the same size, but two have a simmer function that cycles the low flame on and off at intervals. In order to achieve “the laziest of simmers” for six hours, my plan was to park the pot over one of these simmer burners, take a few minutes to dial in the right interval, and let it sit.

But things went haywire. If I left the sauce alone even for a few minutes, I’d come back to find that the sauce’s placid surface was concealing a furious chaos of scorching down below. The level of heat it took to get “an intermittent bubble breaking through to the surface” was somehow producing a layer of superheated sauce at the base of the pot. If I turned the heat down to stop the scorching, the sauce would cool to below 145°F (63°C) despite the flame clicking ineffectually off and on beneath it, entering the “danger zone” at which bacteria can grow.

Reader, I sat by the stove for six hours, nudging the heat up and down, checking its temperature, and stirring. In order to get anything else done — setting the table for 12, taking a shower, making the rest of the meal — I had to dash away, rush through the task, and then hurry back to see what had befallen my sauce. Had it gone tepid and turned into a soup of poisonous bacteria that would kill everyone? Had the bottom inch caramelized into a burnt mass? The good news is that none of that happened — the sauce was fine and my guests loved it. The bad news is that rather than the gracious and relaxed hostess I wanted to be, I felt harried and exhausted.

But worst of all, I felt stupid. Why couldn’t I get that pot of sauce stable at a low simmer?

I’ve had plenty of time to think about what was going on and I think it was an unfortunate confluence of circumstances. The heat cycling system of the Thermador applies flame in short bursts to a narrow ring on the underside of the pot. Iron is not a very conductive material, and so those brief flashes of heat were not spreading horizontally across the broad base of the pot. The only heat getting into the sauce was in that narrow ring where the flame actually contacted the iron, and the sauce was so thick that it wasn’t convecting heat anywhere else very well. In other words, any heat that was getting into the sauce was staying right where it was unless I stirred it.

(I should note that when I told this tale of woe to my mother, she suggested kindly that perhaps I could have just set the oven for 160°F or so and put the pot in there. This is the kind of thing that experienced cooks who are not panicking would know to do, but it did not occur to me because I am not an experienced cook and I was panicking.)

So what to do?

This was the moment when I first thought seriously about cookware materials. Everybody says that an enameled cast iron Dutch oven is the perfect cooking vessel and yet it did not work very well on my stovetop. Was it worth tearing out my stovetop to make a cast iron pot work better? Of course not. But did a different type of pot exist that would be more effective on the stovetop I have?

The stewpot

A thick copper stewpot is ideal for long slow cooking of stews and braises because this is a situation where copper’s best qualities really shine (no pun intended). Unlike soups, stews can scorch: water’s convective currents normally spread heat throughout the pot, but a stew’s solids interrupt that circulation. The result can be pockets of liquid that heat up beyond 212°F (100°C) and can’t escape — the liquid becomes steam and scorches the solids around it until you stir the pot and let the hot steam out. A good conductive stewpot can help avoid this by spreading the heat out around the body of the pot to help compensate for the limited convective currents of a thick stew. The stew receives that heat more evenly and is less likely to superheat in spots.

And this stewpot has plenty of copper to make that happen. It’s 34 centimeters (just over 13 inches) in diameter and 3mm thick; the body of the pot without its lid weighs 8404g, or about 18.5 pounds.

It is an absolute unit.

Its handles and rivets are beautiful. That brass handle with the graceful point on the underside is very similar to what I see on French work. The interior rivets are flat and flush-set, which I associate with 19th century custom-made rivets before the mass-produced round-headed rivets came into use around World War I. However, this is Belgian work and not French, and I am not as confident about the timing of the transition from hand-made to machine-made rivets.

It carries three stamps: “H. POMMIER BRUXELLES” for its maker; “34” for its diameter in centimeters; and “ML” for its owner.

The lid of this pan is a beautiful piece of work in its own right. It weighs 2290g, just over five pounds.

The lid handles are fastened with two copper rivets on each side. The brackets have a rounded and sort of puffy appearance that is distinct from the French style. Compare the Pommier handle on the left to a J. Gaillard handle of roughly the same era. The Gaillard bracket is flatter and has a more pronounced point.

This lid has another unusual feature: a dot in the geometric center under the handle. My understanding is that this divot is a sign of hand craftsmanship because it marks the center of the piece of copper that was hand-cut into a circle.

This pan looks to me to have been made with a mixture of modern and hand techniques. Take a look at these seams: they are welded, not dovetailed. Acetylene torches were invented in France in 1901 (and continue to be used to this day by Mauviel and others), so welded seams like this are most certainly a sign of 20th century manufacture.

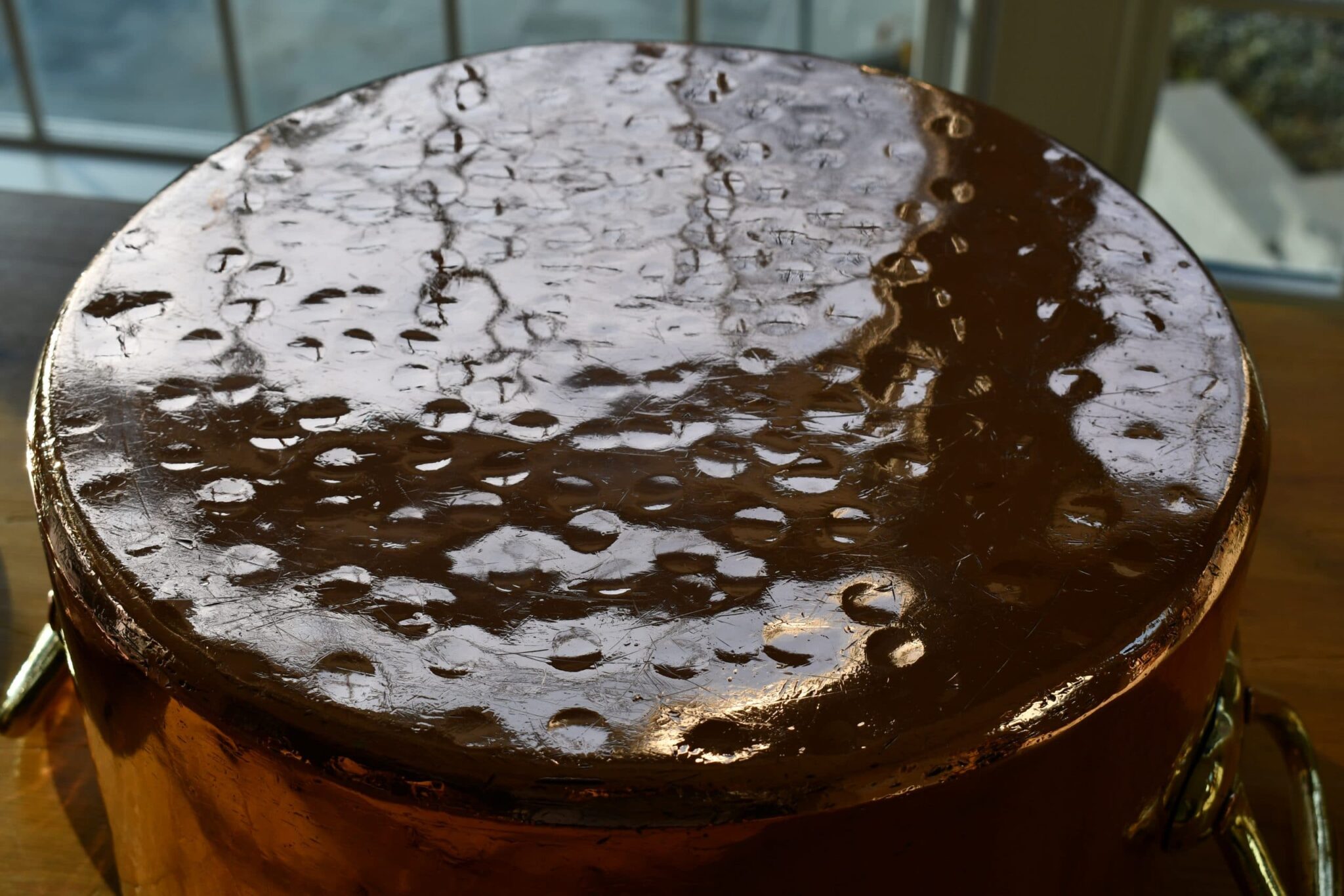

The base of the pan has some unusual hammering on it. The strikes are shallow and while they’re fairly evenly distributed over the surface, the pattern is irregular. My working theory at the moment is that this is hand-hammered.

Given the mixture of machine- and hand-craftsmanship of this pan, it’s difficult to pinpoint its age. H. Pommier began producing copper pans under his name around 1899 (initially stamped Van Neuss-Pommier) and continued working into the 1940s. This pan was welded but not machine pressed and the lid was cut by hand, and my best age estimate is that it was made in the 1910s to 1920s or so.

This pot came to me from lazylou2002 in pretty good shape. I actually liked the patina it had — you can see in particular the contours of the hammered base — but the timing lining was worn through in spots. I don’t mind elderly tin if it’s in decent condition but I decided that the spots of exposed copper needed to be addressed.

I sent it to Erik Undiks at Rocky Mountain Retinning for restoration and he did beautiful work.

If you’re just getting into vintage copper or looking to expand your batterie de cuisine, I suggest you consider a 3mm stewpot. This one is pretty big at 34cm, but you might look for one at 28cm (11 inches) or thereabouts. I fairly frequently see 28cm stewpots on eBay and Etsy at 3mm thick, both antiques like this one or vintage Mauviel from the 1970s and 1980s. The tall sides mean they can be more expensive than other pots with less mass of copper in them, but then again, that mass is exactly what you want!

Epilogue to my story

I’ve come a long way since that day that I hovered over the stove for six hours, unable to get my quirky stovetop and stolid cast iron Dutch oven to work together to stabilize my Bolognese sauce. I have learned a lot about cooking, how to diagnose problems with a dish as I’m making it, and what to do to rescue it.

But I also started buying thick vintage copper and discovered that it makes cooking easier and more pleasant for me. I think of my copper pots and pans as allies as we work through a meal together; if I do my part to use my head as I cook, my copper is right there with me to help make my food just as I want it to be.

I haven’t used this stewpot yet, but I think I’ll try the Bolognese again. I’ll let you know how it goes.

voulez vous me le vendre? [email protected]

Oh Alain, je suis vraiment désolé, mais je ne vends pas mes pots en cuivre! J’ai acheté celui-ci de lazylou2002 sur eBay en Angleterre. Il y a aussi FrenchAntiquity sur Etsy en France qui accepte les demandes de recherche de pièces spécifiques. Je liste mes vendeurs recommandés sur cette page – https://www.vintagefrenchcopper.com/buyers-guide/where-i-buy-copper/

Bonne chance à toi!