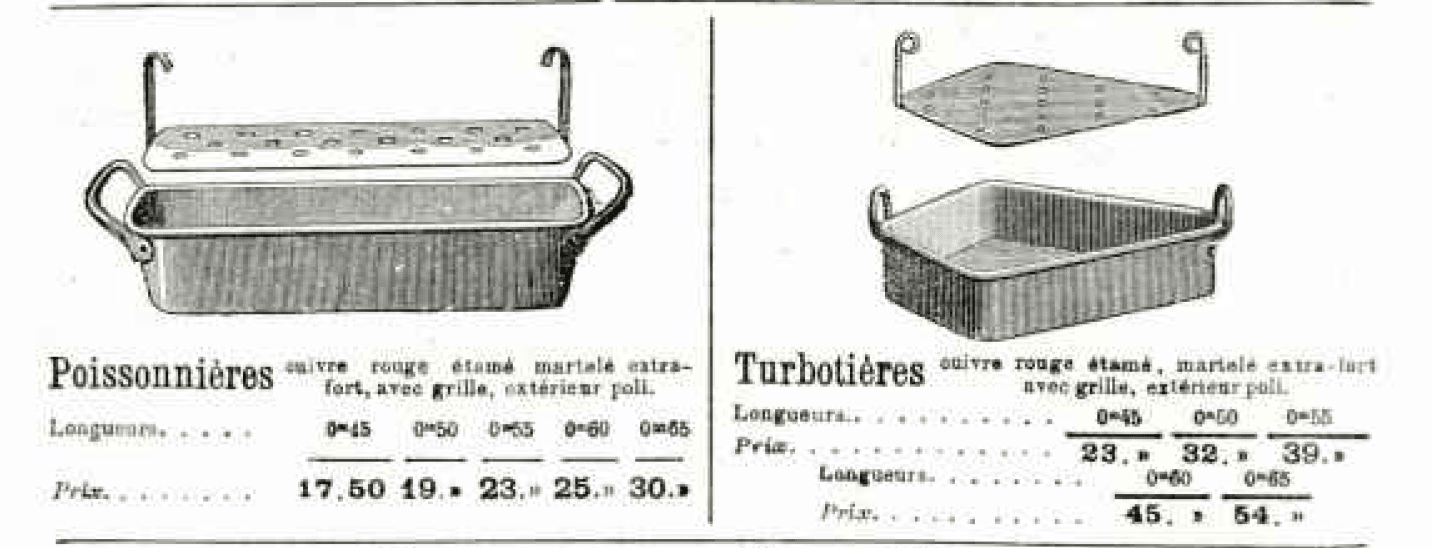

These kite-shaped fish poachers are perhaps the most eye-catching piece in the classic French batterie de cuisine.

- Type: Tin-lined turbotière with brass handles attached with three copper rivets

- French description: Turbotière étamée avec poignées on laiton munies de trois rivets en cuivre

- Dimensions: 50cm long by 40cm wide by 11cm tall (19.7 by 15.8 by 4.3 inches)

- Weight: Approximately 6000g (13.2 lbs)

- Stampings: None

- Maker and age estimate: Unknown, likely French; 1880s to 1930s?

- Owner: Roger W.

French cuisine has a reverence for whole poached fish, and antique French cookbooks have extensive recipes with a range of sauces. Crucial to the enterprise is the presentation: the fish must be laid across the plate, tender filets intact, head attached and fins unfurled, draped with herbs and sliced lemon and enrobed with a delicate sauce to delight the eye as well as the palate. What greater challenge — and triumph! — could there be than the mighty turbot, Scophthalmus maximus, a large kite-shaped “important food fish” found in the Atlantic and Mediterranean waters of Europe.

According to the redoubtable Auguste Escoffier writing in Le guide culinaire in 1903, turbot may be cooked by court-bouillon (literally “brief boiling,” but colloquially referring to poaching in broth) whole or by service de detail (pre-cut filets). Of the six broth formulas A through F that he provides, he recommends “Court-bouillon D”: per each liter of water add 12 grams of salt, one deciliter of milk, and a slice of lemon peel. Place the fish in the broth at room temperature and bring it gently to a boil; once at boiling, reduce the heat to just under the boil and allow 12 minutes of cooking time per kilo of fish. (He advises that if one is cooking the whole fish one must take special care to restrain the head of the turbot to prevent detachment.) If the fish is not to be sauced, the simplest presentation is to spread a bit of butter over it pour en donner du brillant (to make it shine) and then garnish with parsley.

(M. Escoffier suggests that it is also possible to braise turbot in an oven, but notes darkly that this method is only for use qu’accidentellement, et dans des circonstances spéciales [accidentally, and under special circumstances]. Should the situation arise — unspecified but almost certainly unspeakably dire — in which the chef must grimly apply himself to this bizarre and non-traditional preparation, M. Escoffier provides clear and calm guidance: start the fish from room temperature; place it on a well-buttered pan so that it may be slid off easily; keep the fish covered at all times and take care to baste it frequently to keep it from drying out; and above all, do not overcook it. Never let it be said that French cuisine cannot be adapted to hardship!)

Given the prevalence of fish in French cuisine, the attention to maintaining the physical integrity of the fish, and the aversion to deviating from the timing of the proper court-bouillon procedure, it should come as little surprise that fish poaching pans of a range of dimensions were relatively commonplace objects in the French batterie of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The crucial feature of this pan is its perforated lifting platform that enables the fish to be promptly raised from the broth when the time comes. Interestingly, catalogs from the late 19th century and into the 1910s show them without lids; I suspect the addition of a lid came later, perhaps the 1930s and thereafter.

Roger W. owns a classic example. Note the kite shape: it is asymmetrical, longer on one end than than other to accommodate the irregular shape of a turbot. At 50 centimeters (20 inches) in length, this is only a medium-sized turbotière — the fish can grow up to twice as long.

As you can see in the photos, this pan is dovetailed with a line of yellow brass marking the seam where the base and side pieces of copper were joined. There is only a single vertical seam under one of the handles, indicating that the sides of the pan are formed of a single long strip of copper.

The pan has a rolled rim, and that’s appropriate for a thin-walled vessel like this one. Fish pans are intended for poaching in liquid cooking and not for sautéing proteins or vegetables, and so they do not need to be made of thick copper. To provide structural reinforcement, a piece of thick iron wire is run around the rim and the copper is curled over it and tucked under. This hidden iron ring helps the pan keep its shape.

Note that this pan has no damage to the rolled rim. The rolling process thins the copper and can weaken it, particularly over a dovetailed seam. As you can see below, this pan has no rim damage at that location.

The handles and rivets are beautiful. The internal rivets are set flush to the inner surface. The handles are made of brass and have a lovely design that curves around the rolled rim to rise straight up. Note the pronounced ribs where the handgrips join the baseplate — this is a design I have not seen on other pans.

You will note that this turbotière is in an unrestored state. It has minute traces of tin remaining and would need to be retinned for use. It is also missing its lifter platform. Says Roger,

Not all fish kettles had lids and I see no sign this one ever did, however the lifter/platform is missing. It could be remade and not much of a challenge in terms of coppersmithing. I picked it up from a charity shop in very tarnished condition, and had to use paint stripper to remove old lacquer. It seems improbable that the tin could have been worn away so completely; I think it must have passed through the antiques trade a few decades ago and been buffed up as interior decoration. It is too big for me to tin with the tools I have and since I am most unlikely to poach a whole turbot it is hard to justify the cost of professional tinning. It is therefore going to remain a shelf queen.

It’s difficult to estimate this pan’s age. Turbotières are still made today with the same pieced construction; the only change was from dovetailing to welding, likely during the 1930s and later. This particular item could have been made any time from the 1880s or so to the 1930s.

While turbotières and poissonières are by no means confined to French cuisine — English cookbooks from the mid-19th century refer to them as fish kettles, just as Roger does above — I do think this particular pan is French based on the design of the handles. I’ve spent some time looking at photos of known English antique fish kettles and the handles tend to have split baseplates, whereas this one has a solid baseplate with a curved underpoint like other known French turbotières. But I have yet to find an example with the exact same handle as this one with its distinctive vertical-set handgrips and projecting ribs. Here are a few French and English examples for you to look at — what do you think?

While turbotières and poissonières are by no means confined to French cuisine — English cookbooks from the mid-19th century refer to them as fish kettles, just as Roger does above — I do think this particular pan is French based on the design of the handles. I’ve spent some time looking at photos of known English antique fish kettles and the handles tend to have split baseplates, whereas this one has a solid baseplate with a curved underpoint like other known French turbotières. But I have yet to find an example with the exact same handle as this one with its distinctive vertical-set handgrips and projecting ribs. Here are a few French and English examples for you to look at — what do you think?

My thanks to Roger W. for sharing these photos. These pieces are rare and it is a real pleasure to get the chance to look at one up close.

References

Escoffier, Auguste. “Le guide culinaire.” Paris, 1903.