These two big pots are a master class in 20th century Gaillard coppercrafting.

| Type | Two tin-lined saucepans in hammered finish with iron handles and brass helper handles fastened with three copper rivets |

|

| French description | Deux sauciers étames et martelés avec queue de fer et poignée ancillaire en laiton munies de trois rivets en cuivre |

|

| Dimensions | 36cm diameter by 21.5cm tall (14.2 by 8.5 inches) |

34cm diameter by 30cm tall (13.4 by 11.8 inches) |

| Thickness | 3.6mm at rim | 2.5mm at rim |

| Weight | 14350g (31.6 lbs) |

11508g (25.4 lbs) |

| Stampings | “J.E. Gaillard 81. Faubourg Saint-Denis Paris”; “36”; “E.M” | “Jules Gaillard 81 Faubg St Denis Paris”; “34” |

| Maker and age estimate | Gaillard; 1903-1920s |

Jules Gaillard; 1920s-1930s |

| Source | Private sale | Etsy |

I love these giant pots with an irrational passion. There’s something marvelous and a little unreal about how big they are. I’m convinced that the helper handle is there just to help carry them around empty; fill them up with an additional 40 or 50 pounds of liquid and nobody would be silly enough actually to try to lift them. I think the handles would just snap off. These pots are not for the faint of heart or weak of upper body.

What they are for is serious restaurant cooking as Gaillard intended. These were made during the first decades of the 20th century; restaurants and hotels and cafés were filled with people who wanted a taste — a literal taste — of the exquisite spirit of the city of lights. And the chaudronnerie Gaillard made the copper pots and pans for the grand hotels to cook for them, thick sturdy pieces that could be relied on to keep every last ladleful from scorching.

And I think they are gorgeous.

The J.E. is made from a single piece of seamless copper. It was shaped from a flat sheet by a machine with a piston that forced the metal into a cup shape, most likely over a series of steps. When the finished item is deeper than it is wide — like this pot — the process is called deep drawing, or emboutissage in French. This pot is quite a bit thicker than the Jules — 3.6mm at the rim, versus the 2.5mm of the other pot.

The Jules, by comparison, is a dovetailed pot, pieced together by cutting “teeth” into one piece of copper, interleaving it with the other, and hammering them together. The seam was then sealed with melted brass, producing the jagged yellow lines on the surface. That yellow seam runs around the perimeter of the base and up the side of the pot under the iron handle; you can see the overlap of the copper at the rim.

The cast iron handles are both of the pillowy French style of this period with a bulbous mass in the baseplate that adds length and perhaps additional strength to the copper rivets that hold it to the pot. Each baseplate is about 18cm wide, but the handle on the Jules is slightly shorter, measuring 34cm from pot to tip versus 38cm on the J.E. The Jules handle is also mounted sightly higher, appropriate to its greater height. But in other respects the iron handles appear identical, made of iron with the same pewter-like sheen and set with the same rake.

The exterior rivets have a markedly different appearance, but I think this may be due to repair and tightening. On the J.E. they have a button-like uniformity, while on the Jules pan they look to have been flattened with a hammer.

The interior rivets for each main handle are as large as one would expect for big heavy pots like these.

Unlike the iron handles, the brass helper handles are set at the same height. The handles themselves are virtually identical, but the younger J.E.’s is about 1cm narrower.

Erik Undiks at Rocky Mountain Retinning did the restoration and, yes, repair of both pieces, as they both had damage that needed fixing. First and foremost, the 36cm J.E.’s helper handle was snapped off during shipping. This is always a risk with shipping big pieces internationally, and particularly when the packages weigh 30 pounds or more, and it’s why I implore sellers to wrap things carefully.

Erik reassured me that he could re-attach the handle prongs with some silver solder that would be stronger than the original brittle brass. I think he did a wonderful job with it, as I had to look closely to see any sign of repair. Thank you, Erik!

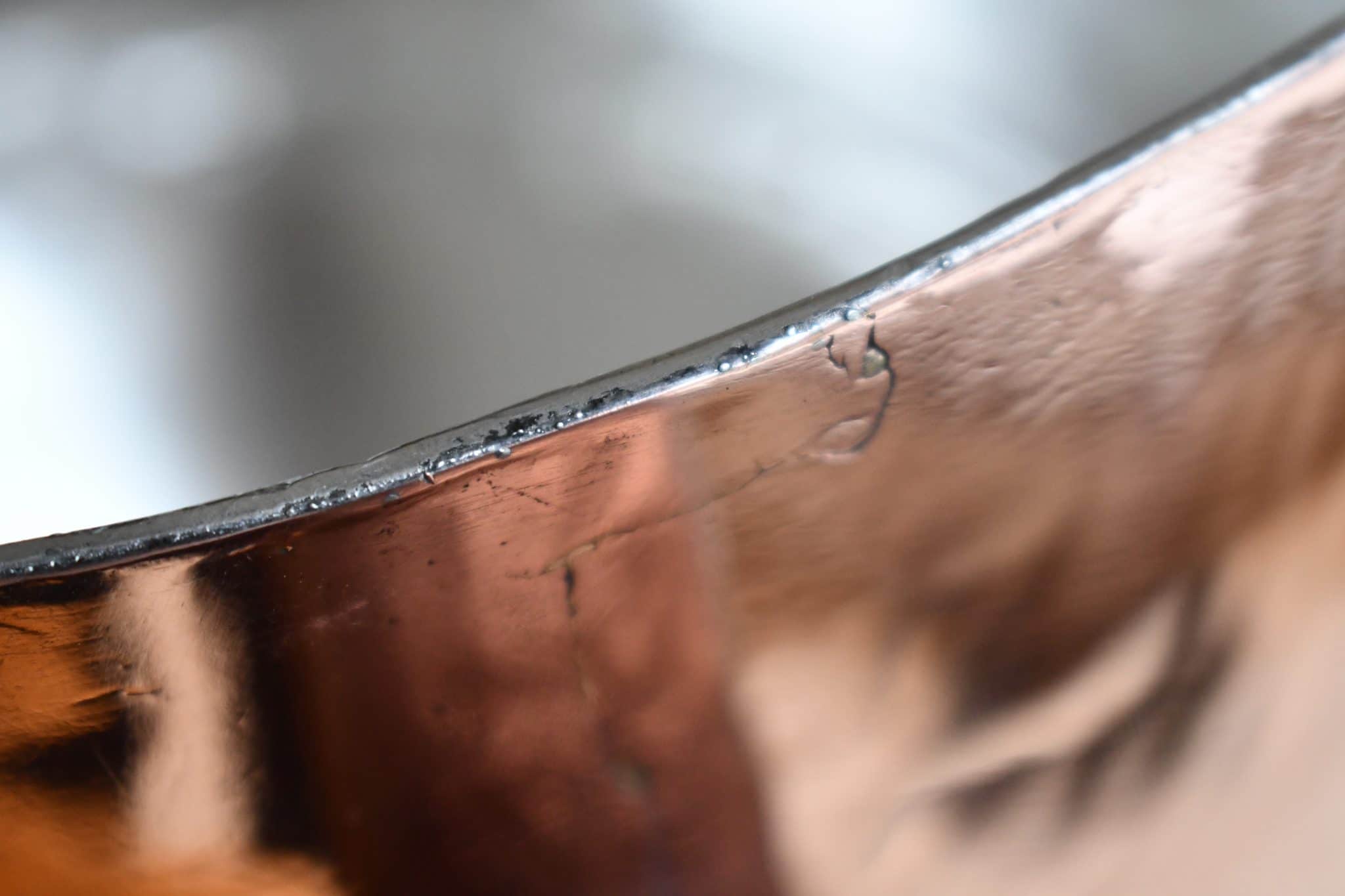

But both pots needed repairs to cracks in the same spot: that vulnerable front edge, the point of the base of the pan opposite the main handle. Both pots have some flattening here and the copper has cracked. Below is the before and after for the Jules repair; I don’t have a before photo for the J.E., but you can see that the finished repair is lovely.

I’d like to wrap up with a good look at the stamps.

These pots are both the work of the house of Gaillard, a storied Paris chaudronnier that spans 1795 to the 1980s. It’s a prized mark on antique and vintage copper for good reason: its pieces are of high quality so they’re resilient and useful in the kitchen, and they’re also sought after by collectors like me. These two pots carry different styles of Gaillard stamps that I believe are quite close in time — from 1903 to about 1919, and then from about 1920 to the 1930s.

I’ve called the 36cm pot “J.E.” because its “J. E. Gaillard” stamp dates it to the family chaudronnerie after 1903 when Jules and Émile Gaillard — brothers or cousins, I am not sure — joined forces. They operated the family firm together until the First World War. That helps to pinpoint the 36cm saucepan to 1903 or later. The Jules stamp followed in the 1920s when he was operating the business under his own name.

Each pot is stamped with its diameter in centimeters, and the 36cm Gaillard carries an additional “E.M”, an owner’s mark.

I know my affection for these pots is a bit irrational. It’s unlikely I’ll use them for their intended purpose — I’m not called upon to cook for a crowd that would require, say, twenty-eight quarts of chili. I love these pots not necessarily for what they are but for what they represent to me (and isn’t that the central psychosis of the collector right there). I love the expanse of copper on their broad flanks; I love the burly bulbous baseplate of the iron handle; I love the elegant brass handle with its delicate curves. And I love their countless nicks and chips and, yes, cracks and scars, too.

Note: This post has been revised in October 2021 based on updated information about the timing of the Jules Gaillard stamp.

Wow! Just lovely. They were restored beautifully. Enjoy them

Very nice! Your posts are always a welcomed distraction.

For you and me both, Mike. It looks like I’ll have more free time than usual over the next few weeks 🙂 so the pace of new posts may increase. Thanks for your kind words.

What great additions to your Gaillard collection! You don’t often find such large saucepans as these for sale. Like you, I doubt if I will be using the extra large commercial grade pans I have in my collection to prepare food but I enjoy just being able to look upon these culinary works of art and thinking of how they have been used in past times to prepare crowd-sized meals.

Awesome pans. Everyone who enjoys this website probably has more pots than you really need to cook. Of course I do too. Love is always a little irrational. How desolate a perfectly rational world would be. Cheers to love!

I don’t think the photobucket images above worked so let me try again:

https://s1053.photobucket.com/user/swhalen10/media/Copper%20Gaillard%20catalog%201_zpsqbqd4wqk.jpg.html

https://s1053.photobucket.com/user/swhalen10/media/copper%201925%20Jacquotot%20catalog_zps5gn4oyrt.jpg.html

Sorry, my last comment applied to another post but from the image of the Gaillard catalog it looks like the 34cm Jules Gaillard pan would be classified as a casserole a jus and may have been available in a tremendous 42cm size!