These mid-20th century Gaillard pans still have 19th-century craftsmanship.

| Type | Two tin-lined sautés in hammered finish with iron handles fastened with three copper rivets | |

| French descriptions | Deux sauteuses étamées et martelées avec queue de fer munie de trois rivets en cuivre | |

| Dimensions | 20cm diameter by 6.5cm tall (7.9 by 2.6 inches) |

24cm diameter by 7cm tall (9.4 by 2.8 inches) |

| Thickness | 2.5mm at rim, thicker in base | 2.5mm at rim, thicker in base |

| Weight | 2360g (5.2 lbs) |

2922g (6.4 lbs) |

| Stampings | GAILLARD PARIS | GAILLARD PARIS; EURO |

| Maker and age estimate | Gaillard; 1930s-1940s(?) | |

| Source | FrenchAntiquity (Etsy) | barttof (eBay) |

| Owner | VFC | Martin |

Reader and copper aficionado Martin is a talented photographer. He’s contributed several guest showcase posts and the photos he’s taken of his copper are just beautiful. His post about photographing copper is a wonderful discussion of light and texture and how copper is both a challenging and rewarding subject. When he shared with me some photos of his 24cm Gaillard sauté pan with the same stamp as my own 20cm sauté, I felt that a tandem post was in order not only to reunite these pieces (if only virtually!).

I believe these pans were made in the late 1930s or 1940s, the period of time after the death of Jules Gaillard, but I don’t know much about the firm’s fortunes during this time. My field guide to Gaillard covers as much of the history as I have been able to substantiate from online sources but as one might imagine this wartime period is sparsely documented. The latest reference I can find to Jules in life is in 1933 at which point he would have been making copper for more than forty years (assuming of course he is one and the same as the Jules Gaillard of the 1890s). The company kept the name “Jules Gaillard” until at least 1938 but by the 1950s was known as Établissements Jules Gaillard et fils (equivalent to an LLC). I suspect the name change occurred sometime in the late 1930s to early 1940s and it was then that they adopted a simple “Gaillard Paris” stamp. From that point until Gaillard’s closure in the early 1980s the firm used four different “Gaillard Paris” stamps; the stamp that these two pans share is the version that I tentatively place during the early phase of that time period, perhaps the late 1930s through 1940s. (As always, if you can point me to documentary sources to confirm or dispute this, I would be very grateful.)

The “Gaillard Paris” stamp on Martin’s pan has been struck more deeply than on mine, which has a more faint “Paris.” But look beyond the thickness of the strokes to the alignment of the letters and you can see that the stamps are the same. This is a genuine Gaillard stamp. I want to be clear about this because I believe there are pieces that have been stamped with a facsimile of this stamp that can be recognized by the different alignment of the letters, and I encourage you to familiarize yourself with both the genuine and facsimile versions before you buy so you can determine whether the piece under consideration is a genuine Gaillard or not.

I make a big fuss over Gaillard pieces from what I call the “golden age” (1880s-1920s or so) when the firm was cranking out huge gorgeously thick restaurant-caliber pieces but the reality is that younger and smaller pieces like these two sautés are much more useful to the modern home cook. As 20th century pans, they would have been shaped with machine assistance: hydraulic-powered cutting dies and metal presses that made short work of what had taken hours of a 19th-century smith’s time. While a collector might sigh at the missing elements of hand-craftsmanship (guilty as charged) the truth is that these machine-aided techniques truly do benefit the cook: the pans are symmetrical, sturdy, and consistent in form and dimension. If the aesthetic downside is that pots and pans of different makers look virtually identical, the practical upside is freedom for the consumer to mix and match lids and pieces from different makers.

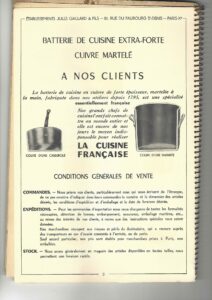

But even in this brave new era of standardized sizes and look-alike pans, Gaillard found a way to add value to its work. Take a look at the frontispiece of the 1956 Gaillard catalog and its message “to our clients”:

The batterie de cuisine in thick copper, hammered by hand, made in our workshops since 1795, is a specialty that is essentially French.

Our great chefs have made it known around the entire world and it is still to this day the indispensable means to realize FRENCH CUISINE.

Aside from the fierce culinary patriotism, two things on this page jump out at me. Let’s take a look at how they manifest in these pans.

“Martelée à la main”

Gaillard in 1956 states that their batterie de cuisine extra-forte cuivre martelé (“extra-thick hammered copper pans”) are also martelée à la main (“hammered by hand”), which I believe refers to the pattern of martelage on the exterior surface. The alternative would have been a hydraulic hammering machine with a piston head; the craftsman would position the pot under the piston and shift it as the piston rose and fell to lay down the hammered pattern. (This is how Mauviel and the other French makers apply martelage to this day.) A hydraulic hammer strikes with consistent angle and pressure over the surface of a pan held steady against a block; if Gaillard was instead hammering each piece by hand, we would expect to see irregularity in the hammer strikes as both pan and hammer would be shifting position as the craftsman worked.

Martin’s 24cm sauté has beautifully clear martelage.

To my eye, the hammer strikes are irregularly spaced, angled, and sized. This becomes more evident to me when I compare Martin’s sauté to the honeycomb-like surface of a 1960s-era 32cm Mauviel for Bonjour pot that was almost certainly machine-hammered.

My pan has not been restored and the surface has been worn down with polishing so the martelage is more difficult to analyze. But I can still spot a similar imperfect pattern.

Another area of hand-hammering is the beveling of the base. My pan has three planes of bevels, while Martin’s pan has two. These bevels are intentionally added as an extra finishing step to confer additional hardness to this vulnerable edge. Not every pan needed bevels — they show up most frequently on stick-handled saucepans and sautés that would be lifted and moved around, while more stationary stockpots and rondeaux would not need the protection. But anywhere a beveled edge appears, it’s a sign of extra time taken to prepare the pan for use.

I have come to consider bevels one of the last vestiges of 19th century chaudronnerie. I find bevels on a range of pans up into the 1920s but the practice dwindles after that, with Gaillard and Jacquotot perhaps the last makers to abandon the practice sometime in the 1940s or 1950s. This 50cm Gaillard rondeau with the same stamp as these two sauté pans also has bevels, but this Gaillard stewpot with a different (and likely later) stamp does not. I see a similar change in Jacquotot: compare these early and late sauté pans and notice that the pre-1930 one has bevels while the later other does not. By the 1960s, I can’t find bevels on any pans, including my own Gaillard saucepans and Windsors.

I suggest that if you’re considering whether a certain 20th-century piece could be unstamped Gaillard (or Jacquotot for that matter), look for bevels.

“Coupe d’une casserole”

If you look closely at the cut-away diagrams you can see that the base of the pans is thicker than the sidewalls. This is intentional, as the more verbose 1914 edition of the Gaillard catalog makes clear: “Cut-aways of kitchen items showing the bases that we make much thicker than the sides in order to avoid burning from heat and which we recommend for all cooking.” This important quality is invisible to the eye (which is presumably why Gaillard added a diagram to their catalogs) but there is another way to detect it.

Below are the weights and measurements I have collected for 20cm and 24cm sauté pans, ordered by thickness at the rim. Notice that these two sauté pans are about 300g heavier than other pans of the same or greater rim thickness. That extra weight comes from thicker copper in the base, just as Gaillard advertises.

20cm (7.9 inch) diameter

| Rim (mm) | Height (cm) | Weight (g) | |

| Mauviel, post 1957 | 3.0 | 6 | 2035 |

| Mauviel for Bonjour | 2.9 | 6 | 2036 |

| Mauviel for Matfer | 2.8 | 6 | 2044 |

| My pan | 2.5 | 6.5 | 2360 |

| Antique Gaillard | 2.0 | 5 | 1310 |

24cm (9.4 inch) diameter

| Rim (mm) | Height (cm) | Weight (g) | |

| Mauviel, mid-20th century | 3.0 | 7.5 | 2950 |

| Mauviel, stainless-lined, post-1995 | 2.6 | 7.7 | 2678 |

| Mauviel, post-1957 | 2.6 | 7.0 | 2696 |

| Martin’s pan | 2.5 | 7 | 2922 |

| Antique | 2.0 | 7.5 | 2516 |

| Antique Gaillard | 1.8 | 7.5 | 2530 |

If it seems that I am nudging you to give more weight (heh) to the weight of pieces you’re considering, you’re right. I’ve put together a reference page of weights and measurements for all sorts of pans in the hope that it’ll help you better understand the composition of copper you see for sale. With this information you can help ensure that you don’t mistakenly pass by hidden gems like these bottom-heavy sautés.

Though these two sauté pans share much of the same craftsmanship, they also have some differences. Let’s start with the rivets and handles.

The interior rivet heads on my pan appear larger and flatter. I see the signs of whacking on the interior heads which could explain the flattening but there is also the fact that the rivets are set differently in the baseplates as well. If you compare the spread and alignment of rivets in each baseplate you can see that Martin’s pan’s rivets are set more widely. I am not certain about this but I suspect that cast iron handles were provided pre-drilled (or cast with holes), and so the different hole arrangement suggests that the handle supplier may have changed between the making of one pan and the other.

Martin’s pan carries the mark of a former owner that has been partially effaced. It reads “EURO” and looks to have been almost worn away with a rasp. While I treasure owner’s stamps, it seems that people at the time were not so sentimental. Once a pot was passed from one owner to the next, oftentimes the old owner’s stamps were obliterated. Though this one is difficult to read (and ambiguous — how many hotels or restaurants were there with this name?), it is still useful as an example of the simple, sans-serif typeface I often see on mid-century owner’s marks, so different from the more elaborate marks of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

My pan has no such stamps on it but bears an owner’s mark of a different kind: black paint on the handle. This is not an option mentioned in the 1914 or 1956 Gaillard catalogs, so I suspect it was done by the owner after purchase. There are traces of black paint around the baseplate and also on the rim on top of the tin.

I don’t think this pan is still on its original coat of tin — it bears too many character marks and the martelage has been softened with multiple polishings. Rather, I think the owner asked the retinner to repaint the handle when it was tinned.

And speaking of tin, this pan’s lining is past its prime.

I purposely did not send mine for retinning as I wanted it to serve as an exemplar of a 1930s-1940s Gaillard pan in the context of the ongoing facsimile stamp issue described above. But as a consequence, I don’t plan to use it for cooking in its current state. The interior tin is aged and there are crusts of oxidation around the rivets. I actually like old tin as long as it has some reflectiveness to it; I find that tin hardens at it ages and becomes a superior cooking surface. (Heat accelerates this process, which is why I welcome the color changes in the tin of my working pans as it’s a sign that the tin is evolving.) But this lining has accumulated patches of crusty oxidation around the rivets as well as a small patch of exposed copper in the center of the base. The exposed copper isn’t yet big enough to be of concern (the general rule is that it’s time to retin when there is one square inch or more of total exposed area), but the crusts around the rivets would need to be removed before cooking, and the scrubbing that would take would likely also wear through the remainder of the lining. For these reasons I plan to send this pan out to be retinned before cooking on it.

As a palate cleanser, and to wrap up this post, please enjoy some bonus photos of Martin’s beautiful 24cm sauté, which is ready to cook up a storm.

I am so grateful to Martin for sharing this beautiful pan with us, and for giving me the chance to engineer the virtual reunion of these two Gaillard pieces.