The weight of this piece and its details make it exceptional.

| Type | Tin-lined daubière with brass handles fastened with three copper rivets and fitted cover with brass handle fastened with two copper rivets on each bracket |

| French description | Daubière étamée et martelée avec poignées en laiton munies de trois rivets en cuivre et couvercle emboîtant avec poignée munie de deux rivets en cuivre sur chaque côté |

| Dimensions | 36.4cm length by 21.4cm width by 19.3cm tall (14.3 by 21.4 by 7.6 inches) |

| Thickness | 2.7mm at rim; lid thickness is 1.7mm |

| Weight | 8200g (18.1 lbs) without lid, 10300g (22.7 lbs) with lid |

| Stampings | “E. DEHILLERIN 18. RUE COQUILLIÈRE” on body and lid; upside-down 2 on body |

| Maker and age estimate | Unknown; 1890-1910? |

| Source | eBay (France) |

| Owner | Stephen Whalen |

This is a daubière, a rectangular pan with a close-fitting lid designed to slow-braise cuts of meat. It is named for the daube, a country stew made with a large cut of tough inexpensive meat transformed to fall-off-the-fork tender after hours of gentle cooking with vegetables, aromatics, and wine. Crucial to the enterprise is to size the daubière to the cut of meat, and so these pans were made in length from 26cm for home cooks all the way to 60cm for restaurants to accommodate everything from chickens and rabbits to lamb, pork, and large cuts of beef. This daub, at 36cm (just over 14 inches long), is a fairly common size among pieces you’ll see for sale on the online marketplaces.

But there is something quite uncommon about this piece: its thickness. The daubières I have seen of this size are about 2mm thick, but this one is a more substantial 2.7mm. That’s just extravagant. Daubières do not require thick copper for their role; braising is wet cooking performed at a low temperature, and the convective currents in the liquid will spread thermal energy and keep things cooking evenly as long as the heat is steadily provided. The copper of the pan needs only to be thick enough to maintain structural rigidity. Smaller daubières tend to be less than 2mm thick and the larger ones — approaching 40cm in length — creep up towards 2.5mm.

So in my opinion, this 2.7mm piece is high quality indeed. It would have been more expensive in its day, perhaps a special order for a restaurant client. It is stamped for E. Dehillerin at the 18 Rue Coquillière address, dating it after 1890. But this stamp does not mean that Eugene de Hillerin made it — this is one of the several “Dehillerin” and “E. Dehillerin” stamps that are quite similar but not identical that I believe represent work from multiple chaudronneries who supplied Eugène de Hillerin’s new retail venture. So this piece could be Dehillerin production, or it could be Gaillard, Legry, Duval, or any number of smaller makers. Whoever it was, they did beautiful work.

So in my opinion, this 2.7mm piece is high quality indeed. It would have been more expensive in its day, perhaps a special order for a restaurant client. It is stamped for E. Dehillerin at the 18 Rue Coquillière address, dating it after 1890. But this stamp does not mean that Eugene de Hillerin made it — this is one of the several “Dehillerin” and “E. Dehillerin” stamps that are quite similar but not identical that I believe represent work from multiple chaudronneries who supplied Eugène de Hillerin’s new retail venture. So this piece could be Dehillerin production, or it could be Gaillard, Legry, Duval, or any number of smaller makers. Whoever it was, they did beautiful work.

The body of the pan carries a second stamp — an upside-down numeral “2” on one end, just below the rim. This is an orientation mark for the lid. Daubières are hand-shaped pieces with some inherent asymmetry and the lids often fit better in one orientation than the other; you will sometimes find a small stamp to show how best to align the lid.

In my opinion, assessing quality on a vintage copper piece comes down to looking at weight and styling details. We’ve already discussed this pan’s thickness, so let’s look at the details.

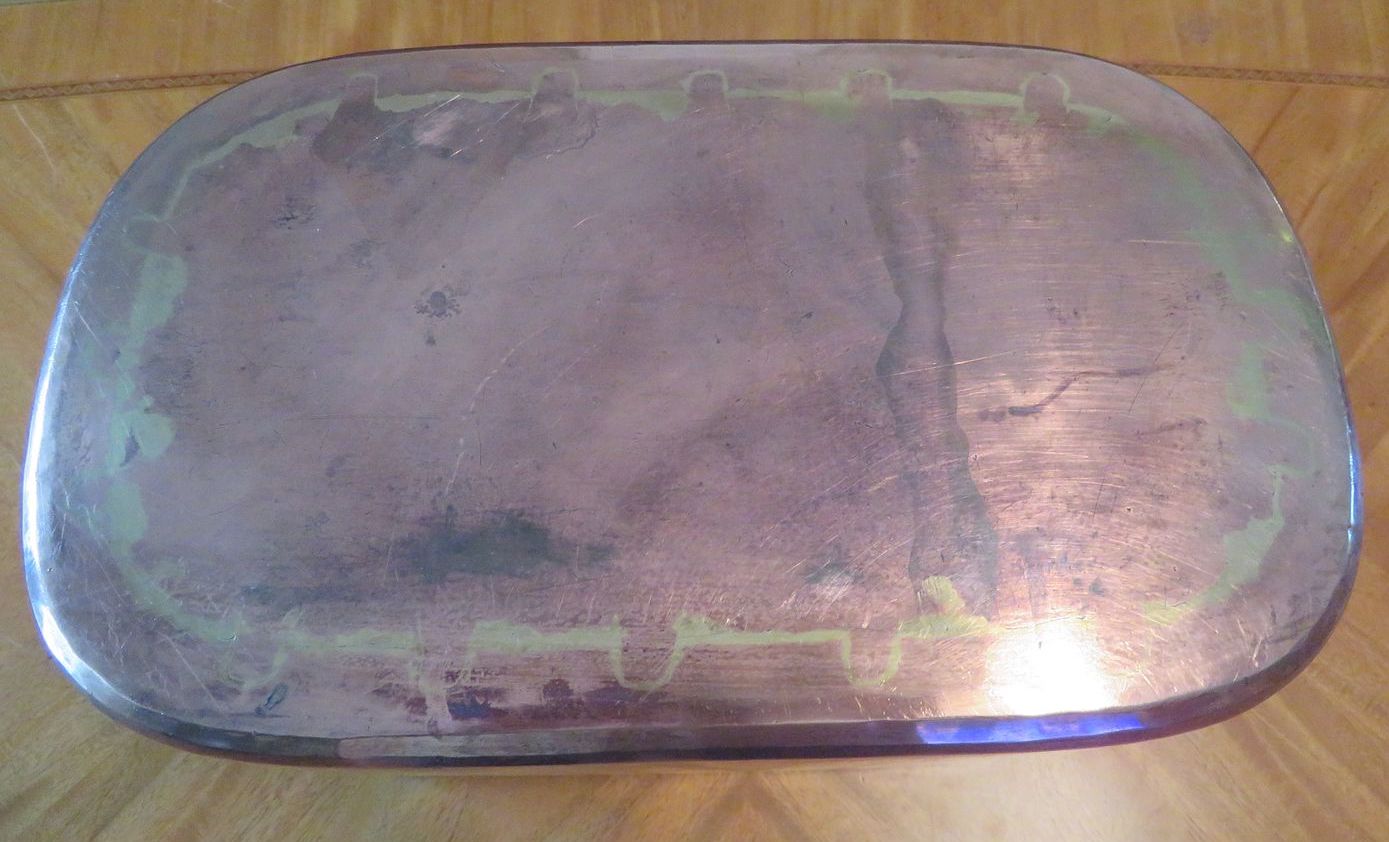

This is a dovetailed piece. The yellow zig-zag lines running around the base and up one side are the seams where sheets of copper were joined to form the pan. Each joined edge was clipped with short flaps that were interleaved and pounded together, and the seam was sealed with molten brass. This was the technique to join sheets of copper before the invention of the acetylene torch in 1901; by the 1920s, dovetailing had been supplanted by welding, which produced a neater and more resilient join in a fraction of the time. The dovetails on this piece are well-made — the cuts are very nearly symmetrical and look flush and smooth to the surface. None looks to have parted.

An important detail is that the base of this piece is beveled. The craftsman took extra time to hammer the outside edge of the base to create two flat planes along the curve from the base to the sidewalls. This is not decorative but an intentional work-hardening step: the hammering toughens the copper and makes it more resistant to dents. Bevels require extra time in the manufacturing process, and seem to have vanished from pans by the mid-20th century. Bevels are a sign of quality on a piece, and the more beveled planes there are, the more time was taken to prepare the pan for service.

The handles are not particularly ornate but have broad baseplates appropriate for a pan that weighs 22 pounds unladen. The exterior rivets are small and rounded and the interior rivets are flat and flush-set to the inner surface.

The lid is where I see more indications of the quality of this piece: the brass handle is attached with two copper rivets on each bracket. Just as the pan body is made of extra-thick copper, so too is this lid — 1.7mm by Stephen’s measurement — and it weighs 2100g, a little over 4½ pounds. But even so, it could get by perfectly well with just one rivet per bracket. Using four rivets to attach this lid to its handle is a stylistic choice, not a utilitarian one, and is another signal of quality. As with the body of the pan, the rivets are polished smooth on the exterior, and flat and flush-set on the inside.

This piece is in fine shape on the exterior. The tin lining has oxidized but there are still some shiny metallic patches, most clearly visible on the interior of the lid. This suggests to me that this pan has only been lightly used and there may be life left in the lining. I’m not sure what Stephen’s plans are for this piece, but it might be possible to abrade away the darker oxidized tin and find enough intact tin beneath it to remain usable.

This is quite a find and I congratulate Stephen on it. The stamp dates it to 1890 at the earliest and I would estimate no later than 1910. It is in beautiful condition — it has been lovingly kept and I am sure Stephen will cherish it as well.