This set of pots aren’t just lovely to look at — they’ve also solved a mystery.

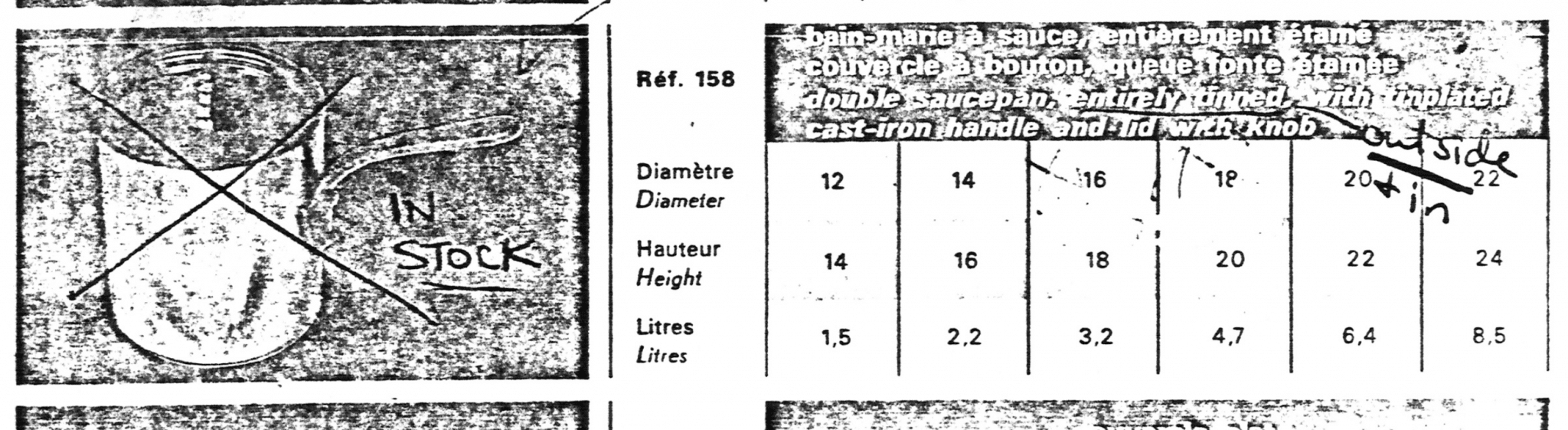

| Type | Three tinned bain marie pots in hammered finish with cast iron handles fastened with three copper rivets and fitted lids with button knobs | ||

| French description | Trois bains maries entièrement étamés avec queue de fer munie de trois rivets en cuivre et couvercles à bouton | ||

| Dimensions | 12cm diameter by 14cm tall (4.7 by 5.5 inches) |

14cm diameter by 16.5cm tall (5.5 by 6.5 inches) |

16cm diameter by 18cm tall (6.3 by 7.1 inches) |

| Thickness | 1.8mm | 1.7mm | 2.6mm |

| Weight | 1000g (2.2 lbs) pot only; 1200g (2.7 lbs) with lid |

1400g (3.1 lbs) pot only; 1700g (3.8 lbs) with lid |

2400g (5.3 lbs) pot only; 2700g (6 lbs) with lid |

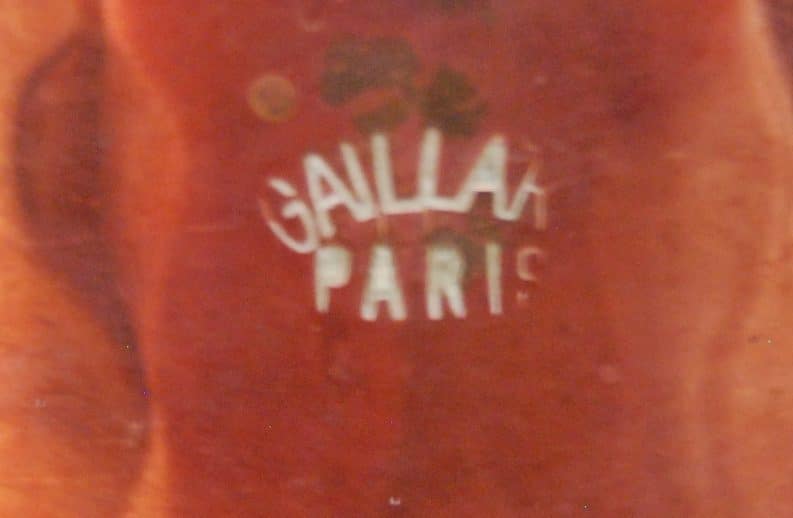

| Stampings | GAILLARD PARIS | ||

| Maker and age estimate | Mauviel for Gaillard; 1960s-1990s | ||

| Owner | Stephen Whalen | ||

French cooking is very serious about the quality and variety of sauces for its dishes, and no self-respecting restaurant would be caught dead without a caisse a bains-marie on the heat with an array of bains-marie à sauce at the ready. The double-boiler is a proven method to provide controlled indirect heat to a liquid; the outer container, filled with water, reaches no higher than 212°F (100°C) and bathes the inner vessels with steady warmth. If you’ve ever scorched a soup or curdled a sauce, you might have wished at that moment for a way to avoid superheating the bottom of the pot — exactly the problem that a bain marie can solve for you.

French cooking is very serious about the quality and variety of sauces for its dishes, and no self-respecting restaurant would be caught dead without a caisse a bains-marie on the heat with an array of bains-marie à sauce at the ready. The double-boiler is a proven method to provide controlled indirect heat to a liquid; the outer container, filled with water, reaches no higher than 212°F (100°C) and bathes the inner vessels with steady warmth. If you’ve ever scorched a soup or curdled a sauce, you might have wished at that moment for a way to avoid superheating the bottom of the pot — exactly the problem that a bain marie can solve for you.

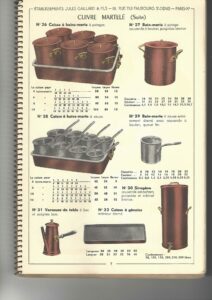

This set of Gaillard bain marie pots belongs to Stephen Whalen and they’re a special find. You will immediately notice that they are tinned on the outside, even the lids. This was intentional: the 1956 Gaillard catalog, as shown on the left, clearly shows and states that the bains marie à sauce are entièrement étamé — tinned inside and out.

This set of Gaillard bain marie pots belongs to Stephen Whalen and they’re a special find. You will immediately notice that they are tinned on the outside, even the lids. This was intentional: the 1956 Gaillard catalog, as shown on the left, clearly shows and states that the bains marie à sauce are entièrement étamé — tinned inside and out.

Why was this done? The answer, my friends, is science: the water bath of a bain marie was intended to be salt water. Early chemists (that is, alchemists) discovered that salt water evaporates more slowly than fresh water. What this meant at a practical level was that if you used salted water instead of fresh water for your water bath, it would last longer before you needed to replenish it. (The marie in bain marie comes from the Latin maris, meaning ocean, which spoken with a French pronunciation sounds just like “marie.”)

We now understand why: salt water has a slightly lower specific heat than fresh water, such that it freezes at a lower temperature and boils at a higher temperature. (The exact temperatures depend on the salinity and ambient air pressure.) Unfortunately, this persistence comes with a downside: corrosion. Copper exposed to salt water and air will rapidly oxidize. You can imagine how this process would go to work on a copper pot sitting for long periods in warm salt water, lifted out every now and then, and replaced for another few hours.

The most straightforward way to prevent this would be to armor the outer copper against contact with the salt, and that’s exactly what they did: in addition to lining the interior of the pot with tin, they continued to tin the exterior as well. So to my mind, the question is not so much why this practice was done but rather why it was ended! I suspect it was an aesthetic issue — as we all know, tin darkens and wears away. And let’s face it: pewter-gray tinned pieces don’t quite have the same visual pizzazz as brightly polished bare copper. Knowing why the tin is there may give you and me a newfound appreciation for the phenomenon, but this is not the sort of thing you’d expect to see on display in Williams-Sonoma.

In any event, it is rare to find a bain marie with intact outer tin. Stephen Whalen has managed to find a matched set of three by Gaillard, complete with their original couvercles à bouton, the button-knob lids.

I think they are gorgeous. Notice how clear the martelage pattern of hammer marks is on the exterior surface. Stephen believes this could be the original tin from Gaillard and I think that’s possible.

These pots have a distinctive handle with a shield-shaped baseplate and a lozenge-shaped hanging loop. This handle does not look French, and to my eye more closely resembles an arrow-shaped English style. But it is most definitely French.

In fact, thanks to reader Michael B. who supplied a 1988 Mauviel price list, I can state with some certainty that it is definitely Mauviel. The item below is this exact piece: bain marie à sauce, entièrement étamé, couvercle à bouton. If you look carefully you can see that the handle has a shield-shaped baseplate. I have one just like it — sadly not entièrement étamé — that my mom bought at Dehillerin in the early 1980s.

Well well well. This is the best evidence I’ve seen that Gaillard was sourcing pieces from Mauviel during the post-war period. According to Jean-Philippe Jacquotot-Carisé, Gaillard and Dehillerin followed the same path as Jacquotot after WWII, choosing to focus on restaurant, hospitality, and catering supply rather than the consumer market. Jean-Philippe tells me that the “big three” (Jacquotot, Dehillerin, and Gaillard) all stopped making conventional copper cookware; if a customer wanted a set of pots, the company would turn to Mauviel or one of the Villedieu makers and add its own stamp to the pieces.

And now we also have evidence of which stamp that was. The Gaillard mark on this pot is a little tough to spot as it’s partially obscured by the tin, but it’s in the usual location to the left of the baseplate. This is the version of Gaillard stamp I call the “small arch”: the letters are tall and narrow in a plain sans-serif typeface. On the right is a clear example stamp from my own daily-use saucepans.

Interestingly, I do not see a “Made in France” stamp on this piece. My current understanding is that the addition of this country-of-origin mark came about as a consequence of the formation of the European Economic Community in 1957. If this pot is indeed not marked like this, it suggests that the piece could have been made prior to that year. Could it be that Gaillard had already begun outsourcing to Mauviel by the mid-1950s?

In fact, could the bains marie à sauce entièrement étamés avec couvercles à bouton shown in the 1956 Gaillard catalog at the top of this post be Mauviel make as well? The bouton knob on those lids does look an awful lot like Williams-Sonoma’s standard acorn knob…

The revelations keep coming! I don’t know how much more excitement I can take! My sincere thanks to Stephen Whalen for sharing this with us, and to reader Michael B. for sharing the Mauviel price list from 1988. Little by little we are making the connections that helps fill the gaps in our understanding of these pieces.

What a treasure! I encourage members of the international community to correct me if I’m wrong here, but I don’t believe European authorities impose any country of origin regulations for products sold within country. Further, English wording would never be placed on goods sold to a French-speaking population. While a country of origin mark can be a clue for dating, the lack of one on a French piece sold through a French channel doesn’t tell us much. My best guess is that this set was purchased sometime towards the end of the era of using water baths in commercial kitchens and set aside because of its inherent beauty and value. Maybe, 1950’s?

Handtinner’s assumption is correct. “Made in …” designations of origin are voluntary in the EU at least until 2013. There is therefore no general obligation to indicate the origin of products offered for sale on French territory. However, there have been various efforts to appropriately label products made in France, initially only to distinguish them from foreign products when sold domestically. An association of manufacturers that inspired this and introduced it in 1929 was “Unis France”. The name “fabrication française” followed later. In accordance with global Anglicization, the “Made in France” (MIF) label has become increasingly common for export goods.

Indeed, the MIF is often interpreted by foreigners as “a guarantee of quality” and “French refinement”. Some sectors of French know-how, including luxury and gastronomy, are now world-renowned.

The development of the designation of origin “Made in Germany” was somewhat different. Originally introduced by Great Britain at the end of the 19th century to protect against supposedly cheap and inferior imported goods from Germany, the name is now considered a seal of quality in the eyes of many consumers.

Could it be that my assertions that the “Made in France” stamp came about circa 1957-1960 be no more than a house of cards? I’ve based that on statements by knowledgeable copper sellers, my own observation of the craftsmanship of “MIF”-stamped items, the sudden appearance of a huge range of “MIF”-stamped items during the same time period, and some research I did a while back on EEC-EU regulations that of course I can’t now pull up for review. Readers, I think it’s time to revisit that assertion. If any of you happen to be familiar with 1960s-era European consumer product labeling policy, I’d welcome your help!

“In the European Union, a state which would make « made in France » or « made in Germany » labelling mandatory would infringe EU law which aim free competition, according to the Court of Justice of the European Union,[2] although « indications géographiques » or « appellations d’origine contrôlée » might exist for food.” Wikipedia

“Dispositifs légaux[modifier:

Il n’existe pas d’obligation générale de préciser l’origine des produits mis en vente sur le territoire français[4].”

read://https_fr.wikipedia.org/?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffr.wikipedia.org%2Fwiki%2FFabriqu%25C3%25A9_en_France

“There is basically no obligation to label with “Made in Germany” if the goods only circulate within the EU. It is only mandatory when exporting goods to countries that require goods to be marked.”

https://www.bergische.ihk.de/international/warenursprung-h/made-in-germany-1409582

I found very complex implementation regulations (sales within a country, sales within the EU, export to a country outside the EU), but only in German.

Problem when an end product is made up of parts that were manufactured in different countries.

“Brussels: There will be no compulsory designation of origin “Made in….” for European products for the time being. Even after the most recent negotiations, the EU member states were unable to agree on a common line…”

https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/international/made-in-eu-drueckt-bei-label-pflicht-auf-die-bremse/11843702.html?ticket=ST-10831234-RgSVmNkmzLrBfUDBOSO4-ap5

“The label “Made in Germany” is not explicitly regulated in German law. Only the trademark law and the law against unfair competition offer clues. Instead of defining the designation of origin, the legislature has limited itself to protection against being misled by geographical indications of the origin of goods. There is no obligation to label. If this is done on a voluntary basis, it must not violate the prohibitions on misleading people from § 127 MarkenG and § 5 UWG. In the absence of legal requirements, labeling criteria were developed as part of judicial training.”

https://wirtschaftsrecht-news.de/2016/01/made-in-germany-auf-dem-pruefstand/#:~:text=Die%20Kennzeichnung%20%E2%80%9EMade%20in%20Germany,Gesetz%20gegen%20den%20unlauteren%20Wettbewerb.&text=Wird%20eine%20solche%20auf%20freiwilliger,und%20%C2%A7%205%20UWG%20versto%C3%9Fen.

I suspect that these statements can be applied to MIF accordingly.

Legal basis:

Madrid Agreement 1891

Union Customs Code (UCC)

Competition law

Trademark Law

Regulation competition

To put it more simply: One has to distinguish between goods that are sold within the country of manufacture and products that are intended for export within the EU and others that are to be exported to non-EU countries. The sale of goods within the EU does not require a “Made in ..” label. However, labeling is optional.

The “made in France” campaign was launched around 2012-14 by the French Minister for Economic Affairs, Arnaud Montebourg, in response to the German “made in Germany”. …. “Montebourg wanted to force the chain stores and retailers to set up entire areas in their stores only for French products. The campaign resulted in a divided response …”

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arnaud_Montebourg

But now I finally have to congratulate Stephen Whalen on his extraordinary and great find, which, by the way, gave us a lot of new knowledge and provided evidence for some assumptions.

Country of Origin Labeleing (CoOL): Ultimately, the EU does NOT regulate the designation of origin “Made in ….”, but the country that imports goods from the EU. So there is no uniform rule. For the USA, however, a designation of origin is mandatory with a few exceptions. In some cases, additional information is required. The designation “Made in EU” is not permitted in the USA (and some other countries).

https://www.stuttgart.ihk24.de/blueprint/servlet/resource/blob/3463212/5f3a32c6785a893c16cafc39025e714e/ihk-studie-ursprungskennzeichnung-2016-data.pdf

I just love the bain maries that Steve is so lucky to own.

I recently acquired two similar pots but not in as good condition and without lids. Both are stamped HATTIER. I can see no other stamp mark. Very informative too from VFC regards the tin outer lining reasoning due to the salt water

One of my pots has the exact arrow head handle plate design as yours and the other is more rounded.

I am not sure that these pans were made by Mauviel. The lovely bain marie pan that you inherited from your mother is very similar to these Gaillard ones but you will notice the top of the “shield” handle where it attaches to the pan is more rounded than the Gaillard ones shown above. I was just looking at some photos of early J. Gaillard bain maries with dovetailed construction that have the identical handles as those pictured in this post. Having said that, the acorn knobs on my Gaillard pan lids seem to be identical to one on a Williams Sonoma soup pot that I own.

Stephen, that’s a good observation. I haven’t made much headway into the historical handle supplier market — it seems likely that the copper cookware makers in the 20th century didn’t cast their own iron and brass, but turned to suppliers. Did each cookware maker commission its own specific design, or did they all use the same handles? The handle is such a strong visual and design element of a piece — it seems counterintuitive to me that multiple cookware makers would use the same one, as it would diminish the unique presence of their brand. But am I imposing a modern commercial sensibility onto what may have been a commodity product in its day? I continue to ruminate on this.

In my opinion, the confusion about the timing of the introduction of the “Made in France” stamp has not yet been completely eliminated. Since the EU has not issued any regulations in this regard, but the US allegedly requires appropriate labeling for goods imported from France, I would be interested to know when the US issued this regulation and what it is exactly. It would be nice if VFC or the American readers could find out.

Martin, the confusion does indeed persist. You did a marvelous job of pulling together information on the recent regulations on EU labeling — thank you. But the fact remains that thousands and thousands of pieces from a range of makers from the 1960s onward were all stamped MADE IN FRANCE, and it cannot be that they all spontaneously chose to add this production cost by coincidence. I have been reading early EEC documents and my current theory is that trade tariffs had something to do with it: the EEC reduced and eventually eliminated tariffs on products sold between member states, but to do so, also by necessity established explicit standards by industry for what qualified as EEC-made. In that context, the cost of adding a “MADE IN FRANCE” assertion to every piece would have been offset by the tariff exemptions at retail stores within the EEC and the benefits of streamlined import duties with foreign trade partners. But this is just a theory — reading 1960s-era EEC trade regulations has been slow going, as one might imagine, and I have yet to find affirmative evidence of this. The work continues…

VFC, I can empathize with your assumptions, but the legal facts are different. At some point, somewhere, I also read the claim that the label MADE IN FRANCE was introduced by the EEC in 1957. But this claim was not proven! Nevertheless, I believed this statement unchecked and unfortunately passed it on. But today I’m more critical.

That is why I have cited numerous reputable sources that consistently show that there is NO LAW in the EU that prescribes a designation of origin “Made in …” – neither in the internal market nor for export. Various regional efforts to introduce such a labeling were ultimately unsuccessful. Some initiatives failed at the European Court of Justice. Therefore there is no authority that checks this label, which manufacturers can apply voluntarily and in their own interest. Today there are many manufacturers around the world who proudly point to the origin of their goods.

However, it is primarily the importing countries that are interested in an indication of origin. After all, it is they who impose tariffs on imported goods in order to protect products made in their own country. Hence my suggestion to check the US import regulations from this period. If there were corresponding customs regulations, the European manufacturers would have had to label goods exported to the US. In this case, you shouldn’t be surprised if you suddenly see a lot of pans with MIF.