This pot is a survivor.

| Type | Tin-lined saucepan in hammered finish with iron handle fastened with three copper rivets |

| French description | Casserole étamée et martelée avec queue de fer munie de trois rivets en cuivre |

| Dimensions | 26cm diameter by 14cm tall (10.2 by 5.5 inches) |

| Thickness | 3mm at rim |

| Weight | 4752g (10.5 lbs) |

| Stampings | J. Gaillard Paris; M F*F |

| Maker and age estimate | Gaillard; 1920s-1930s? |

| Source | Private sale |

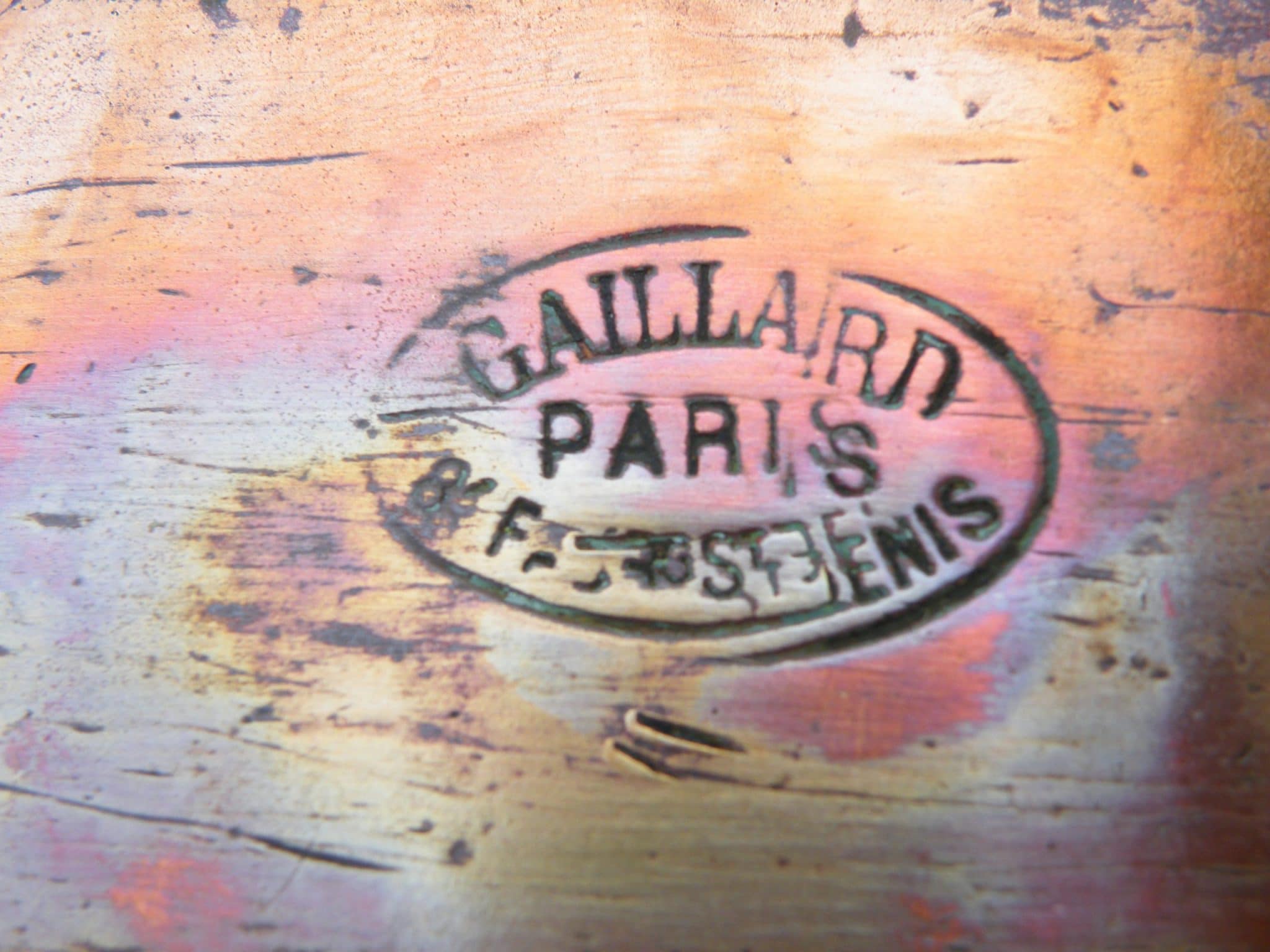

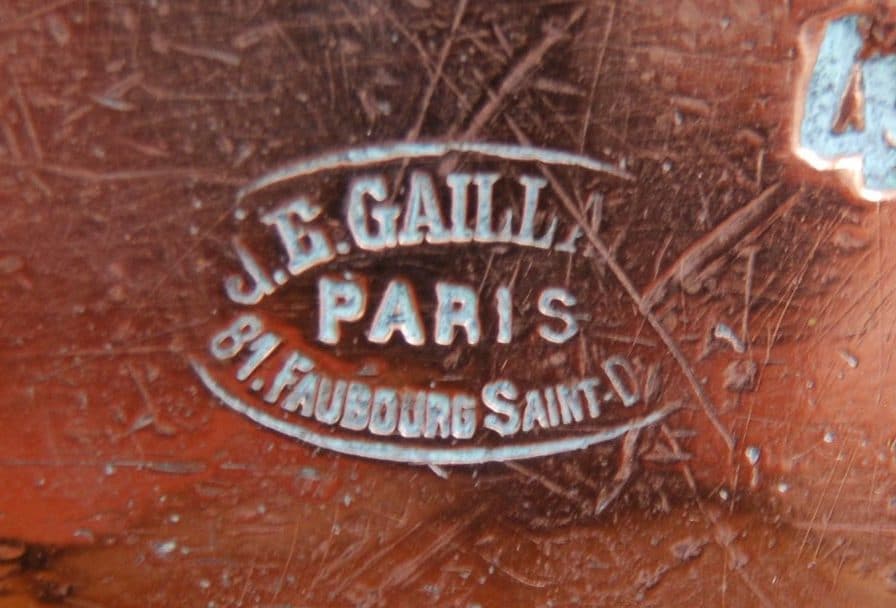

I’d like to start by looking at the stamp on this piece. It’s hard to read: it’s partially obliterated with scratches and it looks like it was not deeply struck in the first place. It’s definitely a Gaillard mark, but which one? There are four Gaillard marks that I’m aware of that have this same configuration. Take a look below: on the left is a close-up of this pot’s mark, and on the right, you can swipe through the four candidate Gaillard marks in the chronological order in which I tentatively place them.

There’s enough of the address line (“FAUBG ST DEN”) to rule out the J&E and J.E. stamps (2 and 3 in the sequence), both of which spell out “Faubourg.” That leaves the first Gaillard stamp (1890s-1900s) and the last J. Gaillard stamp (1920s-1930s). Look at the letter A’s in the “Gaillard” and “Paris” of the mystery stamp on the left — they are almost stacked one on top of the other. To my eye, the strongest match of the stacked A’s is to the last stamp in the candidate series, the one for J. Gaillard. (I say a strong but not absolute match because I still see very subtle differences, but I would chalk them up to a replacement stamp rather than an altogether different design of mark.)

That match is what leads me to estimate the date of this pan to the 1920s to 1930s. I consider this period of time to be fin du siècle: the last period of Jules Gaillard’s life, the end of the first golden age of French copper, and the end of the period of time I call antique. The last holdouts of the hand-crafted techniques of the 19th century were giving way to the improved efficiency and durability of the mechanized tools of the 20th. To me, this pot perfectly captures that moment.

First and foremost, it was assembled with brazed dovetails (more correctly called cramp seams), which was the method of joining copper until the advent of industrial-scale welding in the 1900s. There is no hard and fast date at which dovetailing fell out of common practice (and of course it is still performed to this day by artisans), but welding offers undeniable advantages in efficiency and durability. The historical research I’ve read posits that welding had supplanted dovetailing by the 1920s, but my guess is that statement was derived from observation of larger-scale industry such as shipbuilding and construction. But the reality is that the Parisian chaudronniers in the 1920s had long had access to hydraulic metal presses and welding torches that rendered dovetailing obsolete. I am coming to see dovetailed pieces of the 1920s as bit of defiance of modernity.

Another throwback to the 19th century is the bevel on the edge of the base. After the pot was shaped, the smith positioned it over an anvil head and laid down a smooth flat plane on the curve from sidewall to base. This work-hardens the copper and makes it more resistant to dents. Bevels are a sign of quality — an extra step to the finishing process that is nearly universal on pans of the 19th century, less common into the early 20th, and virtually out of practice after WWII.

The cast iron handle is another special element on this piece. It is beautifully finished, smooth and pleasant to hold, with a texture almost like skin. I know that comparison sounds a little creepy but I don’t know how else to describe it — I suspect it was smoothed after it was cast to produce a high-quality finish that resembles a wrought piece. My research on iron handles suggests that the transition from wrought to cast handles occurred towards 1890, and for a period of time cast iron handles were carefully finished to give them the appearance of the smooth wrought iron they replaced. This handle would seem to have gotten that same treatment: it has no rough edges anywhere. I count this as yet another late 19th century element on this pan of the 20th.

So how can I be so sure it was cast? Simply put: no grains. Wrought iron has small dark streaks of slag called grains that follow the contours of the shape. Cast iron, by comparison, is a homogenous mixture that does not have grains. The fine file marks on this cast handle are a surface texture but not the deeper striations of grains. Compare this cast handle on the left below with the wrought iron handle on an 1890-1900s Gaillard sauté on the right.

A second signifier is that this pot’s handle has some pitting. Wrought iron is chemically distinct from cast iron, and one consequence is that wrought handles resist rust. I have been lucky enough to acquire a few wrought-handled pieces and the iron is in miraculous condition. By comparison, my antique cast-handled pans often show pits and rough patches where rust has eaten away at the metal. This pan has a few deep pits on the handle shaft and some rough patches on the baseplate where the smooth finish has been eroded. This is just a cosmetic issue at this time, but when I wash this pot I will want to make sure that moisture isn’t sitting in those holes.

The point at which I am attempting to arrive, a little haltingly, is that I believe this pot’s dovetails, bevel, and extra finishing to the handle were deliberate choices at this time of production. There were “better” options available — that is, faster, less expensive, and just as durable (if not more). If I am correct in my research, this was the final era under Jules Gaillard, he who first put out work under his own name in the 1890s and lead the family firm for another forty years. I cannot help but sense his touch on this piece.

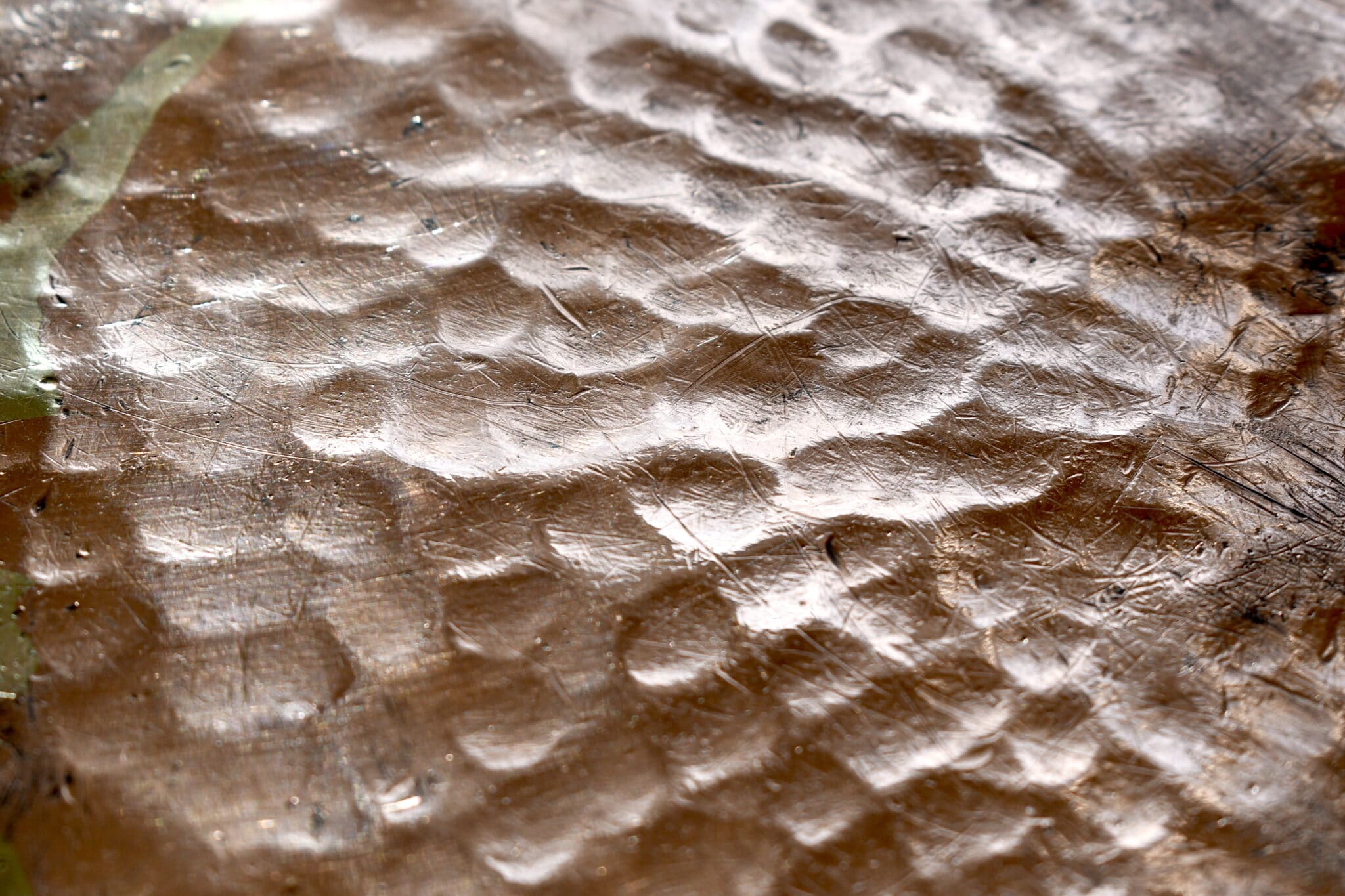

I’ve saved the most interesting (to me, at least) for last: the base of this pot. It’s hammered, which in my experience is very unusual for a Gaillard piece.

I do not think this pot left Gaillard like this, but instead that the hammering is the consequence of an expertly-done repair. The darkened area at the center of the base in the photo above corresponds to a crease, visible in the photo below. This is almost certainly the remnants of damage that has been addressed with some serious hammering.

One of the most common areas for damage in antique and vintage copper that I see is distortion to the base — it’s an unreinforced expanse of ductile copper, and when excessive force is applied to the metal it will obligingly stretch. The challenge for repair is that copper cannot be made to un-stretch, so bringing the base back to flat means finding an accommodation for that excess surface area. The most common solution is to pop the bulging spots back into the interior volume of the pan and try to even them out with hammering; the result is usually serviceable, as the pan will sit more flat for cooking, but the floor of the pan becomes a bit wavy. This is not a dealbreaker for a wet-cooking piece like a stockpot or stewpot but can be frustrating for a sauté pan or rondeau, as oil will not spread evenly but instead will pool in the low-lying areas of the contours of the pan’s floor.

But that is not what was done to this pot. Instead, the smith managed to shift the stretched copper to form a small crease at the center of the base. I expect this took quite a bit of work to nudge the bulge to the middle and flatten the surrounding area, and my guess is that the smith finished the repair with an even overall hammering. I find it beautiful.

You know I am a little nutty about copper [narrator voice: “nutty” is an understatement] but I have to say that this piece really speaks to me. The outer surface is pockmarked with dings and scratches like the nicks and scars on the hands of an experienced chef. (My thanks to Val Maguire at Southwest Hand Tinning for her sensitive restoration that preserved that texture.) Areas of the rim has acquired a slight lip from thousands of sharp raps with a spoon. Pieces like this give me confidence when I cook with them, like a well-used tool that slips into your hand at just the right position.

Whoever owned this piece before me used it well but also loved it enough to care for it. And here it is, in wonderful shape.

Copper like this is a reminder that well-made things last. This piece is so thoughtfully made — thick 3mm walls, rock-solid dovetails, a beautifully finished cast iron handle mounted low for superior leverage — that it is as sound today as it was when it began its work a century ago. What a pleasure — and privilege — to have it now.

I was really interested in the repair to the bottom of this pan. It would have had to be annealed to soften the copper and then the hammered and planished to move things around enough to eventually flatten a warp or bulge.

I tried a little research on repair of copper and found the John Fuller book to be the best source of examples.

I did wonder if the pan warp were to be really egregious, why wouldn’t they just cut out a circle and insert a new bottom with cramp seams. Looking around, and voila! On the VFC website, in the section about dovetails – the very first image. It looks like someone cut in a replacement bottom. https://mk0vintagefrencppu2c.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/all-about-dovetails-2-scaled-1120×650.jpg

Is there any other reason for the bottom to have been treated this way? Have you seen this treatment on other pans?

Do you have any other repair examples? Might be a good topic for a separate post.

Heya Roger! Yes, here’s the piece: https://www.vintagefrenchcopper.com/2018/12/40cm-stewpan/

I don’t know why the 40cm stewpot was repaired with dovetails while this 26cm saucepan was not. Could the issue be diameter? I have seen a few dovetailed pieces with second dovetail repairs and they’ve all been big ‘uns, like the 40cm stewpot pictured. Could it be that below a certain diameter, it was too difficult to cut out the section for the dovetails? This saucepan is 3mm thick — could the thickness combined with the small-diameter cut have been the deciding factors?

I’ll look through my posts but at the moment I think that stewpot is the only double-dovetailed piece to which I have access. Do any readers have pans repaired like this that they can offer as examples?