Reader Javier O. introduces us to the Spanish coppersmith José Preckler and Sons.

Javier is sharing his beautiful pan stamped for Hijos de José Preckler, a family metalworking firm founded in Barcelona in 1875 and continuing into the 1930s. The company manufactured and installed industrial water heating systems, chimney and ventilation systems, and stoves, especialidad construcción de cocinas económicas (specializing in the construction of economical kitchens).

Javier is sharing his beautiful pan stamped for Hijos de José Preckler, a family metalworking firm founded in Barcelona in 1875 and continuing into the 1930s. The company manufactured and installed industrial water heating systems, chimney and ventilation systems, and stoves, especialidad construcción de cocinas económicas (specializing in the construction of economical kitchens).

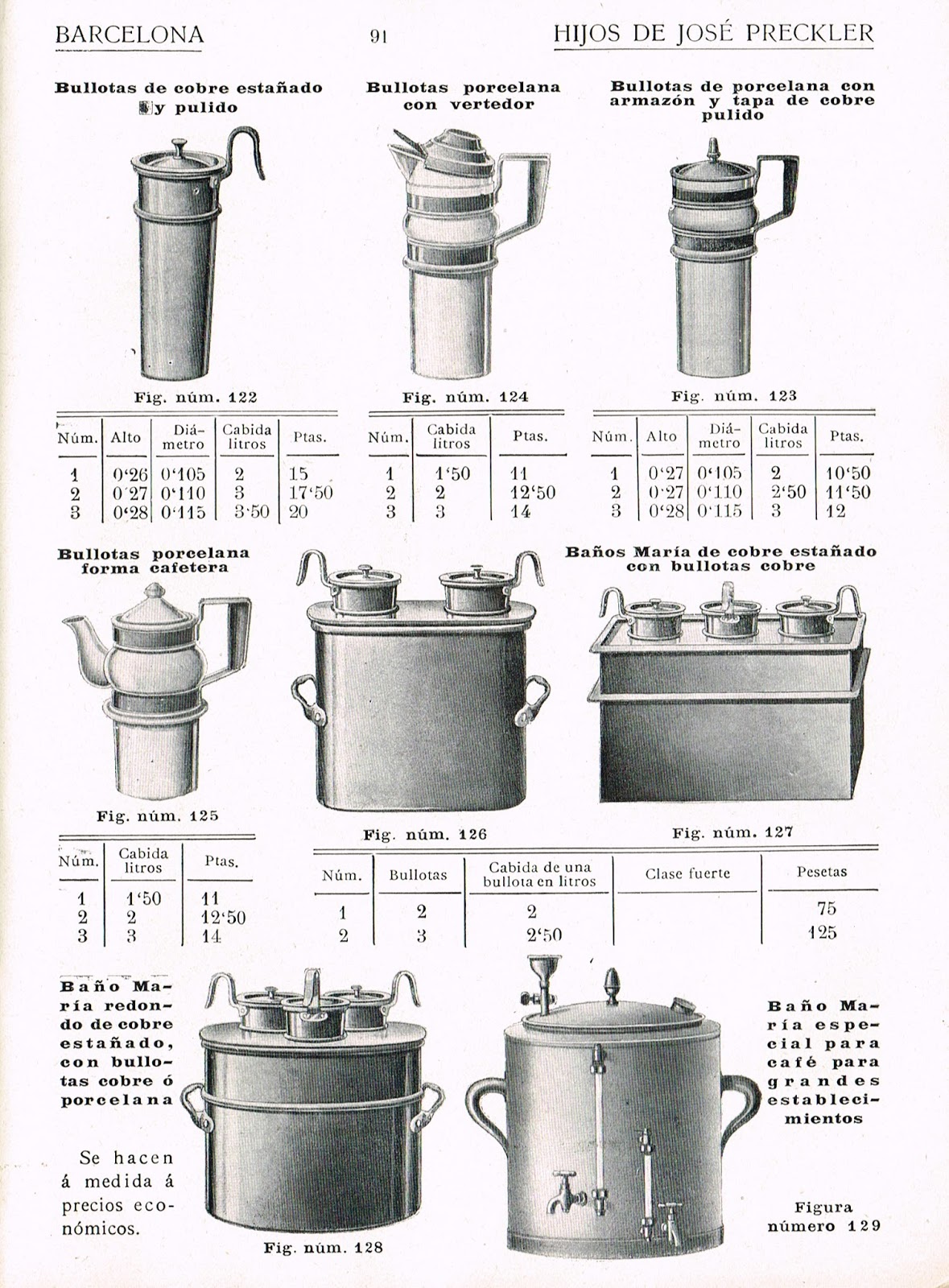

By 1903 the business was handed to his sons: an advertisement from that year shows the company renamed from José Preckler é hijos (and sons) to Hijos de José Preckler (sons of). The company catalog of 1908 focuses primarily on elaborate caloriferos sistema Preckler but also a range of kitchenware products. The blog Els Potols Mistics Catalans has a marvelous post “The Preckler House: The interiors of Catalan kitchens and homes from 1900” with scans of the entire 1908 catalog and I encourage you to read it — the ironwork stoves are magnificent.

Among the numerous models of water heaters, central heating systems, and kitchen stoves for every budget is an array of kitchenware items (these scans are examples from the blog above):

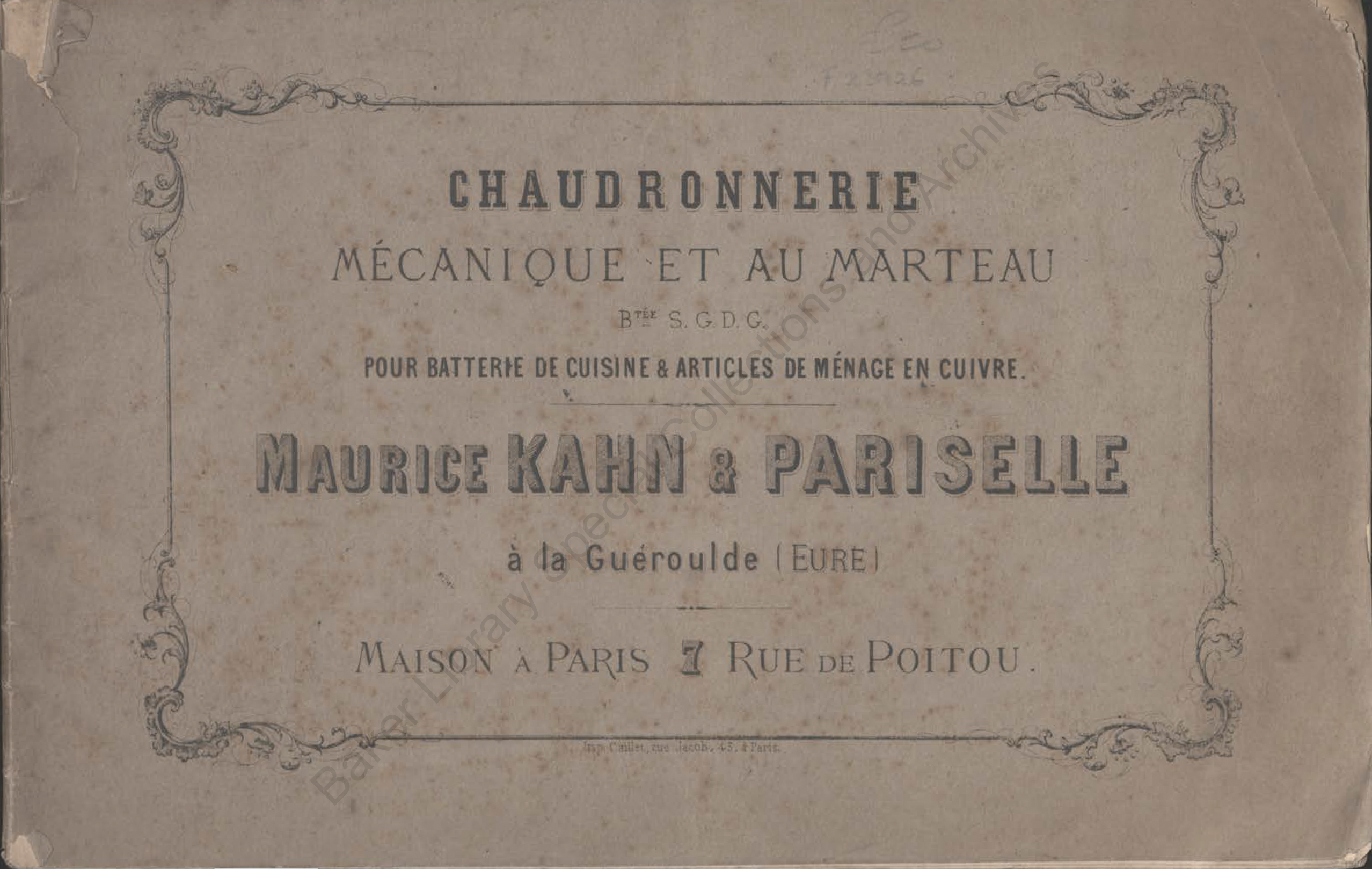

The company continued into the 1930s but I do not know when (or if!) it ceased operations. The company reminds me strongly of Gaillard and Jacquotot of the same era, and no doubt there were fine hotels and restaurants in Barcelona and Madrid with an array of Preckler pots and pans atop one of the gran cocinas para casas particulares importantes.

The company continued into the 1930s but I do not know when (or if!) it ceased operations. The company reminds me strongly of Gaillard and Jacquotot of the same era, and no doubt there were fine hotels and restaurants in Barcelona and Madrid with an array of Preckler pots and pans atop one of the gran cocinas para casas particulares importantes.

At first glance the pots and bains maries in the catalog look very similar to the French pieces of the same era that we know so well. But though one saucepan can look just like another at first glance, there are always differences between the makers. What I immediately found interesting about Javier’s saucepan is the dovetailing.

Look closely at the photo at right: the base of the pot is joined to the sidewalls by a brazed cramp seam (a so-called “dovetail”) about an inch or so above the bottom of the pot. This means that the base piece is cup-shaped and the sidewalls are a simple cylinder. Compare this construction to antique-era dovetailed French saucepans and stockpots: the base piece is a flat disk, and the bottom inch or two of the sidewalls is bent inward and joined to it.

If I saw this construction on a French piece I would immediately assume it was some sort of repair, but it’s clear that this is the original and intentional construction of Javier’s pot. Take a good look at the detail photos below.

I asked Javier whether he had seen more Preckler pans with this style of dovetailing and he was able to find a few more examples. This saucepan below shows the same dovetailing around the sidewalls.

Here is a nice rondeau with the same seam.

These few examples are enough to convince me that this pattern of dovetailing is not a repair but in fact the original construction of the piece. This leads me to wonder if this dovetailing style is a hallmark of Spanish coppersmithing, an aesthetic signature similar to the distinctive handles and other stylistic details that immediately distinguish French from English work.

This set of four unstamped sauté pans (currently listed on Etsy) caught my eye a while back — the seller describes them as French, but to my eye they do not have the French aesthetic. Now I wonder if they are Spanish! I do not believe these are Preckler — the lipped rim and the dovetailing cuts are distinctive enough to mark the work of a different hand, in my opinion — but I am certain there must have been more Spanish coppersmiths whose names are lost to us now. (Whoever he or she was, the work is magnificent — look at how fine and even those dovetails are!)

And you know what else this makes me think of? That’s right — Frankenpan. Could what I thought was a Frenchman with an unusual repair be instead a proud Spaniard? Perhaps I owe this pan an apology!

Finally, I have a question for readers with a metalworking background: is this construction an improvement over the French style? Dovetails are vulnerable to tearing and separation and I wonder if positioning the dovetail on the side of the pot places stress on the seam in a way that is less likely to damage it. When a French pot is heavily loaded, the dovetail on the underside of the base bears a perpendicular force: the dovetail could be punched through, so to speak. But with the join on the sidewall of the pot, the dovetail experiences a lateral force that seeks to slide the interleaved pieces apart. Are dovetails better able to withstand lateral stress than perpendicular stress? I ask because I can’t help but notice that modern welded pieces — stockpots and daubières, for example — all appear to have sidewall seams. This suggests that the transition from dovetailing to welding in the first decades of the 1900s also shifted the location of the join from the base to the sidewall. I imagine this could have been due to the size and configuration of welding equipment, but I wonder if the repositioning of the join was also done as an improvement for structural integrity. Readers with experience in this, what do you think?

My sincere thanks to Javier O. for introducing us to the work of José Preckler and Sons, and for revealing a style of construction that may prove to be a way to identify Spanish craftsmanship.

It is always instructive to think outside the box and study production methods in other countries. As someone who lives in the middle of Europe, I have of course always enjoyed visiting our neighbors over the past few decades and have benefited from the diversity of European culture. ¡Saludos cordiales a los vecinos catalán-españoles!

On connection technology: As a layperson, I can only make an assessment based on my gut feeling. I imagine joining two cylindrical parts (cup-shaped bottom and the side wall) using dovetails to be more difficult than inserting a flat disc on the base using the dovetail technique. I suspect that the “Catalan” technique also has static advantages, as the “teeth” wedge together when the filled pan is lifted (climbers use similarly shaped clamping wedges to prevent falls). Since the pan bottoms are the most stressed, I also see a disadvantage here if there are comparatively sensitive brazed seams at this point. On the other hand, I find the “French” method aesthetically more convincing and more elegant, as the “patchwork” is cleverly hidden.

Hey Martin! I wish I knew more about the actual experience of dovetailing! I know certain metal smiths practice it still, but welding has become the standard for these joins.

I think its interesting that pictures 15-17 show a dovetail form that I’d associate with woodworking, while the others have the more commonly seen tooth wedge.

Bryan, that is indeed an interesting observation! I wonder whether the carpentry-style cuts make a difference. As far as I know, the cut pieces simply lay on top of each other — I’m curious as to whether the angled cuts change the surface area of contact or something like that.

Bryan, unfortunately, the term “dovetail” has been generalized to most types of gearing in the English-speaking world. I find that regrettable because the manual effort and the effect for a real dovetail is much greater. With joiners and carpenters, this connection is considered to be highest quality and particulary stable. Especially with tensile strain, as you can easily imagine. You do not necessarily have to glue this type of connection between wood.Therefore I believe that the real dovetail connection also has advantages with copper. Among other things, this increases the length of the seam and should therefore ensure more safety.

“In Corsica” I found a Gaillard Saucepan 35×20 cm, made around 1900, with an attached pan base. But to my surprise, the “dovetailing” is not located at the base, but in the lower area of the side wall, as we could see with the Preckler pan from Spain presented here. I had seen the offer on Leboncoin several times, but so far I had noticed this striking detail in the photos. This method of horizontal dovetailing on the side wall seems to have been more widespread in Europe.

https://www.leboncoin.fr/decoration/1931762788.htm?ac=206978287

Is it possible this is a Gaillard pan that had the bottom section replaced due to extensive damage. We have seen other examples of these expensive pans that underwent substantial rebuilding rather than discarding them. If this is the case with this particular pan it seems to have been expertly done.

Steven, this possibility must be taken into account. Unfortunately, I did not receive an answer to my questions from the seller. Maybe he was scared off by the bad French (automatic translation). However, the response rate to my inquiries by email at Leboncoin is generally extremely low. Most sellers prefer telephone contact.

Could someone help me to identify this copper cauldron, or point me in the right direction, please. Thank you.I randomly came across this forum, searching for vintage copper identification. Well, unfortunately, i cannot post a photo

Hi Kristi! I’ll send you an email so you can send me the photos. Thanks!