“So after a while of hesitation, I bought the two pans. Now you know what my good intentions are worth.”

VFC says: Please enjoy this guest post, written and photographed by our German experts Martin and Arndt!

Last fall, Arndt brought to my attention an offer from a Berlin resident who wanted to sell two saucepans and a small frying pan. Although all three pans were stamped with coronets, I stayed true to my offset of not increasing my collection any further. Arndt then decided to buy the small frying pan, but which he wanted to use as a lid. It came as it had to come, the two saucepans were no longer out of my mind, especially since a first, superficial research had shown that all stamped coronets actually represented royal crowns. So after a while of hesitation, I bought the two pans. Now you know what my good intentions are worth.

First orientation

Glasshouse and similar pages in Wikipedia provide a good introduction and overview of the insignia of European nobility and its ranks. However, in the effort to bring a system to the insignia of the nobility and to mimic the originals of the time as graphics, small but essential details were repeatedly not correctly reproduced as a result of the necessary abstractions. This becomes clear very quickly when one compares photos of original crowns with the corresponding graphics. An Albrecht Dürer could have put each crown perfectly on paper, but with a system of easy-to-grasp graphics, other requirements apply.

Contemporary witnesses

To be able to clarify the provenance of a crown, I am looking for “contemporary witnesses”. In addition to photos of the originals, which are not always easy to find on the internet, if at all, historical coins, antiquarian books and letters, seals, cast iron coats of arms (on monuments, castles, official buildings and state institutions), historical ceramics and furniture etc. can be helpful. In the case of coins, it is important to note that they are really from the respective time and are not replicas from later decades (such as jubilee coins). With money coins, you can practically always assume that they are genuine witnesses of the times. In addition, many good photos of original coins can be found on the Internet.

Kingdom of Württemberg

While some collectors prefer “giants”, I am increasingly discovering my love for “tiny ones”. After all, they have all the craftsmanship of their big brothers and sisters, just on a smaller scale. That’s why they find ample space in my kitchen.

Matching my small pan “Queen Victoria” held a few weeks ago another small royal saucepan entry into my “court kitchen”. Its origin became a joyful surprise. But until I could classify this new arrival historically, I had to travel virtually through several European kingdoms on a kind of odyssey: Hanover, Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria, and Austria. Even a sea voyage to the island of the United Kingdom was necessary. My odyssey was neither as far nor as adventurous as that of Ulysses, but for me this trip was extremely exciting and finally brought me to my destination – back to my immediate homeland. Now to the sober facts as I see them.

Characteristics of manufacture

The saucepan measures 9.5-9.8cm tall by 8 cm in diameter and has a small spout to facilitate pouring. It weighs 485 grams. At first glance, the handle of the small pan shows similarities with handles found on French saucières, casseroles or russes as well as on saucepans of the United Kingdom. But there are differences. Similar to some French pans, the support plate of the handle forms a kind of arrow. Because of the gentle curve of this triangle, which is nearly isosceles in my pan, you can also see a leaf shape or heart in this.

British pans, on the other hand, show a rather sharp-edged arrow as the support plate. However, the near-horizontal shape of the handle and the slightly tapered keyhole lug agree well with some British pans. French pans, however, almost always have a nicely curved handle.

In short, the design of the handle is “unique”. The handle is fastened with 3 copper rivets made and hammered in by hand, a typical mark of a 19th century manufacture. The material of the handle is “wrought iron”, as I learned at VFC; well recognizable by the elongated grooves. I have never held such distinctive grooves of a handle in my hands before. Presumably, this roughness was exacerbated by decades of corrosion. However, as a side effect, the grooves increase the grip.

The sheet metal used in making the pan is 1.2 mm thin; it was easy to work by hand. The bottom is inserted interlocked (“wolf teeth” or “dovetails”), the sheet metal of the side wall is joined in the same way. Unfortunately, my pan has no maker’s stamp, but based on the design features, the period of manufacture can be set to the 19th century (probably around the middle).

The pan was carefully retinned by the Atelier du Cuivre in Villedieu.

Stamps

Since the stamped crown initially refused a closer determination, I turned to the back of the pan. Will the numbers and letters . 1 lb . 16 lth . on the back of the pan help in identifying the origin?

Well, lb is the abbreviation for the weight measure pound (Latin libra pondo, pondus), as it is still used in the Anglo-Saxon world today. Hence my spontaneous jump to the British island. Here I got lost several times, until the message reached me that this lb was common all over Europe in the 18th/19th century, partly even at the beginning of the 20th century. The stamp clearly shows the old spelling for pound, as it was common on the continent. Only now did I remember that my mother still maintained this spelling and had taught it to me.

But what do the next letters lth and the number 16 mean? Presumably, this is the old weight measure Loth (lot). 1 lb corresponds to 16 ounces/oz or 32 Loth = 453.6 g. Thus, the number 32 should actually be stamped before lth, if it should correspond to the preceding indication 1 pound (lb). I searched for a long time in old weight measures (there are hundreds), but found no explanation.

But what do the next letters lth and the number 16 mean? Presumably, this is the old weight measure Loth (lot). 1 lb corresponds to 16 ounces/oz or 32 Loth = 453.6 g. Thus, the number 32 should actually be stamped before lth, if it should correspond to the preceding indication 1 pound (lb). I searched for a long time in old weight measures (there are hundreds), but found no explanation.

Finally, it occurred to me that both measurements could be used independently. If you fill the pan with water (not quite to the rim), the volume is equal to 470 g, or about 1 pound or a scant half liter. Since an old, imprecise but descriptive guide measure for 1 Loth is equivalent to a heaping spoonful, I then spooned flour into the pan. Lo and behold, it fit 16 heaping spoonfuls of flour. Perhaps the pan could be used to weigh both liquid and dry quantities. Anyone have a better idea?

Now I turned back to the front of the pan and there the stamp N.P. under the crown and the inventory number No 97 of a presumed court kitchen.

I checked the names of hundreds of castles and palaces in Germany (there are supposed to be 25,000!) to see if there was a match for the abbreviation N.P. Neither in the Kingdom of Saxony, nor in Hanover did I find anything. Only the “New Palace” in Berlin could correspond with the abbreviation. But Berlin is Prussia and here there was no match of the crowns at all. After close examination, the crowns of Saxony and Hanover were also ruled out. I will spare you detailed explanations.

After I had not found anything in the north and east of Germany, Bavaria and Austria could be excluded quickly, I turned already rather despondently to the small Kingdom of Württemberg in the southwest of Germany. Here, too, one tried to confuse “Ulysses” with monograms of “typical” German royal crowns with stemmed pearls between the temples and other features. But as my previous research showed, this standardization often neither corresponds to the individual characteristics of the royal houses in the German-speaking countries, nor could be distinguished by their reigns.

After I had not found anything in the north and east of Germany, Bavaria and Austria could be excluded quickly, I turned already rather despondently to the small Kingdom of Württemberg in the southwest of Germany. Here, too, one tried to confuse “Ulysses” with monograms of “typical” German royal crowns with stemmed pearls between the temples and other features. But as my previous research showed, this standardization often neither corresponds to the individual characteristics of the royal houses in the German-speaking countries, nor could be distinguished by their reigns.

Therefore, I applied my method “contemporary witnesses” and came across money coins of that time (“Gulden” and “Kreuzer”).

I found an old drawing of the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Württemberg, and most importantly, photos of the real royal crown of Württemberg. This crown was made as early as 1797 and was reworked in later years. What we see today is the result of several changes under King Wilhelm I. The diamonds and emeralds are from older times.

I found an old drawing of the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Württemberg, and most importantly, photos of the real royal crown of Württemberg. This crown was made as early as 1797 and was reworked in later years. What we see today is the result of several changes under King Wilhelm I. The diamonds and emeralds are from older times.

In contrast to the monograms, I found a very good match with the stamped crown on the pan in “contemporary witnesses”: relatively narrow and straight arches (temples) with large emeralds and arrangements of countless small diamonds, with a round of diamonds encompassed by leaves immediately in front of the circlet. No stemmed pearls between the bows, as mistakenly seen in modern monograms, but a browband with multiple curves at the top, adorned by garlands of diamonds. Below this, a horizontal string of pearls. Naturally, not all details can be reproduced exactly on a 1 cm² small stamp, but I was finally convinced to be able to assign the crown.

Final stage of determining the provenance of the sauce pan

Now “Ulysses” had almost reached his destination. But to which reign of the four kings of Württemberg can the pan be assigned? I found well preserved money coins for all reigns: Frederick I (FR = Fredericus Rex, reign 1806-1), William I (reign 1816-1864), Charles (reign 1864-1891) and William II (reign 1891-1918).

Coins from the time of Karl and Wilhelm II already show the crown of the German Empire, to which the Kingdom of Württemberg belonged at that time. Thus, this period could be excluded. The crowns on coins from the reign of Friedrich I bear only a rough, less differentiated resemblance to the original. Since forged handles were common at this time, but the handle of the pan is cast (or drawn) from wrought iron, Friedrich I is also ruled out.

An almost perfect match of the stamped crown was found with the crowns on coins from the time of Wilhelm I. (William I).

Since the characteristics of the manufacture described at the beginning also fit this period, I can assign the provenance of the pan to King Wilhelm I and thus to the period from 1816 to 1864.

Since the characteristics of the manufacture described at the beginning also fit this period, I can assign the provenance of the pan to King Wilhelm I and thus to the period from 1816 to 1864.

More unproductive were attempts of an interpretation of the abbreviation N.P., thus probably for the kitchen of a palace. A very vague conjecture could refer to the “Kronprinzenpalais” (Crown Prince Palace) in the capital Stuttgart, built 1846-1850. Since there is still an “Altes Kronprinzenpalais” (Old Crown Prince Palace also called “Erbprinzenpalais”) in the immediate vicinity, one might presume somewhat presumptuously that the new “Kronprinzenpalais” was given the abbreviation N.P. (New Palace). This would in turn mean that the pan could be attributed to King Wilhelm I, who commissioned this new building. The building was unfortunately completely destroyed during WWII.

Be that as it may, “Queen Victoria” can now parley with a “royal colleague” from Württemberg, even if King Wilhelm I played a far less important role in world history than the British queen and empress. However, this Württemberg king was a reformer who laid the foundations for developments that continue to this day. Wilhelm I was supported by the great social commitment of his wife Queen Katharina, daughter of the Russian Czar Paul I.

Kingdom of Prussia

Make

The saucepan measures 21cm diameter by 13.8cm and weighs 2.487g. It was made of 1.6 mm copper sheet (measured at the rim of the pan). The use of this relatively thin material was typical for the 19th century, as it was easy to work by hand and less expensive. However, the bottom should be made of about 2 mm material, as my measurements at various points on the bottom indicated. The essentially manual manufacture can be readily seen in the dovetailed inserted pan base and the equally dovetailed joined side wall. This work is meticulously done and hardly noticeable on cursory inspection.

The handle

The connecting plate of the handle shows a gently rounded arrow shape (similar to a leaf or heart shape) and is reminiscent of both French “casseroles” and coppersmithing from Eastern Europe. The handle is fastened with 3 hand-made and hammered-in copper rivets. The horizontal orientation of the handle again indicates a commonality with other makers of cookware of this period in the German-speaking world, such as Gebr. Schwabenland (Mannheim, Berlin, Zurich) and Fauser & Sohn (Vienna). But Polish and Hungarian coppersmiths also used similar handles.

The pan was carefully retinned by the Atelier du Cuivre in Villedieu.

Provenance

The casserole can be clearly assigned to the Prussian royal and imperial house, as is already evident from the stamped crown. This stamp coincides with great detail with the graphics or monogram of the Crown of Prussia.

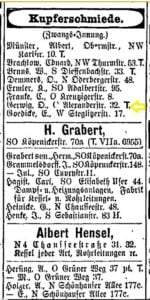

The maker’s stamp “O. Gerwig Berlin” underlines my assumption.

“O. Gerwig, Kupferschmied” (coppersmith) is listed among a large number of coppersmiths in several editions of the Berlin address book between 1880 and 1912. In 1880 under the street address “Grüner Weg 86”, in the years 1890, 1901, 1903 and 1912 always under the address “Alexanderstr. 32” (with district information O or C). A telephone connection is noted from 1901 (“T”).

Unfortunately, I have found hardly any further information about this coppersmith. Only the auction of a beautifully crafted copper vessel with lid from the Imperial Majolica Manufactory Cadinen indicates that O. Gerwig also made other objects of copper for the Prussian royal family (by the way, the plain vessel of about 15x15cm achieved a price of 1,200 €).

Thus, the saucepan dates either from the time of King Wilhelm I (1861-1888 and from January 18, 1871 in personal union German Emperor) or from the time of Wilhelm II, who was King of Prussia and German Emperor from 1888 until his abdication in 1918. With Wilhelm II, the rule of the nobility ended in Germany, which henceforth became a republic. Although a German Emperor ruled over several royal houses and principalities, his possessions were limited to his own kingdom. Therefore, the pan is marked only with the Prussian crown and not additionally with the imperial crown. Imperial crowns, on the other hand, can be found on the new money coins from 1871.

Thus, the saucepan dates either from the time of King Wilhelm I (1861-1888 and from January 18, 1871 in personal union German Emperor) or from the time of Wilhelm II, who was King of Prussia and German Emperor from 1888 until his abdication in 1918. With Wilhelm II, the rule of the nobility ended in Germany, which henceforth became a republic. Although a German Emperor ruled over several royal houses and principalities, his possessions were limited to his own kingdom. Therefore, the pan is marked only with the Prussian crown and not additionally with the imperial crown. Imperial crowns, on the other hand, can be found on the new money coins from 1871.

The abbreviation S. K. directly under the crown is often found on copper pans of German castles and stands for Schlossküche (court kitchen). This is immediately followed by two other abbreviations M.Berl, for this I found no sure interpretation, although I checked this abbreviation with all the castles in and around Berlin.

Conceivable would be Marmorpalais Berlin, a summer residence in Potsdam, just outside Berlin. With its many magnificent palaces surrounded by water and manicured landscaped gardens, Potsdam is one of the most beautiful royal residential cities in Europe. However, I am puzzled by the strange abbreviation Berl. Why should just two letters have been omitted?

Marmorpalais Berlin

“The Marble Palace is romantically situated on a terrace complex directly on the lakeshore in Potsdam’s New Garden, close to Berlin. King Frederick William II had the building, which is clad in Silesian marble, built as a summer residence in 1787-1793. His architect Carl von Gontard created the first and only Prussian royal palace in the style of early classicism.

The king, who was musically inclined and associated with the ideas of the Rosicrucians, used the palace and garden as a private retreat.”

Pan of a Saxon king

The pan and lid

Arndt acquired this pan because it can be used as a lid at the same time. We know these variable devices also from French manufacturers. It is a small pan/lid measuring 19cm diameter by 4cm and weighing 830g.

What I find most striking is the copper reinforcement ring around the side wall and the straight, horizontally protruding handle with a rectangular mounting plate.

Both the reinforcing ring and the handle itself are fastened with handmade and hand driven rivets. The material of the handle is likely wrought iron, as I suspect based on the rough texture and numerous grooves. The straight-line design of the handle is a pretty sure indication that the pan was made in Germany or Eastern Europe.

The lid was mirror retinned by Arndt himself and harmonizes well with one of his pans.

Provenance

The very well preserved stamp of a royal crown on the bottom of the pan undoubtedly corresponds to the crown of the Saxon royal house, as can be easily verified from monetary coins.

Theoretically, 5 Sachsen (Saxon) kings who ruled between 1836 and 1918 are eligible:

- Friedrich August II (1836-1854)

- Johann (1854-1873)

- Albert (1873-1902)

- Georg (1902-1904)

- Friedrich August III (1904-1918)

With the beginning of the reign of a new king, new money coins were always minted. How quickly old coins were exchanged for new ones is not known to me. The coins usually showed the portrait of the king, his name and title on the obverse. The reverse was decorated with the national coat of arms or the crown of the respective kingdom. In addition, the value of the coin was embossed here.

Below, as an example: (obverse) IOHANN V.G.G. KOENIG V. SACHSEN, (reverse) EIN VEREINSTHALER XXX EIN PFUND FEIN 1871

Such coins for each king can be found quite easily via Google at corresponding dealers. Other “contemporary witnesses” can be seen in and at castles, in museums and at monuments from the respective time. One only has to start a virtual sightseeing. Since the 3 pans are German products, I had it easy to browse corresponding German sites on the Internet.

The crowns of the respective kingdoms of Hanover, Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria, Württemberg differed in many details. It is too tedious to describe these differences in detail in English. But if you compare these crowns with each other, you will find the differences. In Glasshouse and partly also in Wikipedia a unified “German” royal crown is depicted, which never existed in such a way, when still different small kingdoms on the territory of the today’s Federal Republic of Germany rivaled with each other. This graphic corresponds most closely to the crown of Prussia.

But Prussia was not Germany! The German Empire was led from 1871 to 1918 by a Prussian king and emperor, but it was still a union of several principalities. In addition to the aforementioned kingdoms, there was also the Grand Duchy of Baden and lesser duchies such as Brunswick, Anhalt, etc. Not only Central Europe, but all of Europe was divided into a multitude of kingdoms, principalities and city-states for centuries. Not to forget the ecclesiastical principalities! As a result of countless wars or due to strategic marriages, the dominions were redefined again and again. Compared to earlier centuries, today’s European Union is truly a peace project, despite some points of contention, as is necessary in democracies.

In narrowing down the five kings theoretically in question, I was able to exclude the last two of these kings with certainty, since Saxony was already part of the German Empire at that time, with the Emperor of Prussia at its head. Therefore, although the profiles of the Saxon kings were shown on the obverse of the corresponding coins, the imperial crown was shown on the reverse. The reign of King Albert possibly fell in a transitional period. But even of him I have only seen coins that already show the Prussian imperial crown on the reverse.

So that leaves Frederick August II (1836-1854) and King John (1854-1873). The coins from the time of both kings show very similar crowns on the reverse, which in turn show high similarities to the minted crown on the pan when compared millimeter for millimeter.

To be able to decide between the kings, I now turned once again to the handle.

Handles from the first half of the 19th century are usually forged and therefore usually show clearly visible hammer marks. Handles made of “wrought iron” have a more “flowing” appearance, as in the case of the handle of this pan. One might think that Prussian discipline has already been perpetuated in this handle and also in the reinforcing ring that oddly surrounds the pan. So I recognize in this handle features that did not become common in Germany until the middle of the 19th century. This handle could also be considered a precursor to the handles on the Gebr. Schwabenland pans.

Conclusion

I suspect with a fair degree of certainty that this small pan dates from the time of King Johann (1854-1873), more precisely from the estate of Johann Nepomuk Maria Joseph Anton Xaver Vincenz Aloys Luis de Gonzaga Franz de Paula Stanislaus Bernhard Paul Felix Damasus, King of Saxony. Interestingly, the old spelling of the name “IOHANN” can still be seen on the corresponding coins, i.e. with “I”, instead of the more modern and unambiguous “J”.

The stamps “HK Hub. No. 28“

HK undoubtedly stands for “Hofküche” (court kitchen). After my search for a castle that could be associated with this abbreviation was fruitless, Arndt found Hubertusburg Castle and thus a good match for the stamp. However, my subsequent research cast considerable doubt on this assignment. The castle served only until 1753 as the residence of Elector of Frederick August II / King August III of Poland. In 1761, during the Seven Years’ War, the magnificently furnished castle was plundered by King Frederick II of Prussia. Subsequently, the large building served a variety of purposes: As a factory, military camp, military hospital, state hospital, state prison and nursing home for the disabled. It is hard to imagine that kitchens of a building complex now used only for profane purposes were equipped with royal cookware.

The location of the court kitchen where this pan was used therefore remains unclear.

VFC says: Thank you so much, Martin and Arndt! Martin, your research is very thorough and thank you for walking us through it. And the photographs are marvelous. Arndt, I must also recognize your restoration work — the mirror finish you have achieved on the tin is comparable to the work I see from Rocky Mountain Retinning and other professional retinners. I am very grateful to you both for building up this site’s materials on German coppersmithing to help readers appreciate this area of history.

Perhaps these little pans were more likely survivors in domestic kitchens than the big pieces. I have a few similar small saucepans marked with French and English aristocratic marks like King Louis Phillipe

Glad you were able to rescue similar pieces from the kitchens of the nobility. Unfortunately, in my experience, very few interesting pieces have survived in Germany in general. What was not melted down or destroyed by bombs during WW II was no longer appreciated during the period of reconstruction (“economic miracle”) and was discarded as old-fashioned stuff. Some copper pots may have survived in castles, but these are generally not for sale. Unless a new generation of nobles wants or needs to part with some possessions. This was the case in 2005 at an auction where a considerable part of the inventory from castles of the former Kingdom of Hanover (“Welfen”) was sold.

Excellent detective work by Martin to determine the origin of these pans. Martin and Arndt exhibit a real love for these old historic culinary copperware pans.

A loyal reader of VFC, as you are, never misses a post or comment. Thank you for your appreciation!

I like the small one. Excellent milk/butter pan; it even has a spout, good for desert making.

At the moment asparagus is in season with us. I like it best with a hollandaise sauce. I used now for the first time my small saucepan from the royal house of Württemberg to melt the butter necessary for this. By the way, I do not need a water bath (bain marie) for whipping the egg yolk. With a little experience, this is quite simple with a “Windsor” saucepan at the lowest heat on the stove. As soon as the yolk begins to thicken, I take the saucepan off the heat and beat the yolk until it has taken on a slightly whitish color. Then I add the warmed (not too hot) butter in a fine stream while continuing to beat. The whisk I use has a somewhat unusual shape. A silicone covered spiral on a handle at a 45° angle. With it you do not beat, but stir on the bottom of the pot.

You clearly have very good technique. For most readers without your experience, to thicken hollandaise, it is easiest to use an electric whisk in one hand and hold a steel bowl in simmering water with the other. 🙂

The 21 is just shy of 22, and 22 sauce pot measures four quarts. 22 is a useful size for small batch making of sauces. A typical 22 stock pot measures out to 8 quarts, or 16 pounds, and has twice the volume of a 22 sauce pot. No lid is needed to make sauces. Lack of a lid is not an issue.