I am pretentious and pedantic, and so I like to use the French terms for cookware and whatnot when there are perfectly good English words for the same things. (And because I’m also a perfectionist, I welcome corrections, amplifications, and suggestions.) I’ve also added a few English words that are peculiar to metalworking.

| Acier | Steel. See also inox, for inoxydable, meaning stainless steel. | ||||||||||

| Airain | An archaic term for a copper alloy that looks like reddish brass. There is no specific formula for airain — it was remixed from melted down scrap from damaged copper pots and pans so it contained a mix of copper, tin, zinc, lead, and whatever other impurities were present. Airain was used by the dinandiers in Villedieu (and its environs) to form cookware and household items. | ||||||||||

| Anneau (plural, anneaux) |  “Ring,” referring to a freely-moving metal loop (usually brass) held in place by a bracket. This is a compact handle style often seen on a shallow pan like a gratin. An anneau is very convenient for hanging the pan flat against the wall but will get murderously hot during cooking, so be prepared with potholders or a side towel when you need to lift the pan away from heat. See poignée for other handle types. “Ring,” referring to a freely-moving metal loop (usually brass) held in place by a bracket. This is a compact handle style often seen on a shallow pan like a gratin. An anneau is very convenient for hanging the pan flat against the wall but will get murderously hot during cooking, so be prepared with potholders or a side towel when you need to lift the pan away from heat. See poignée for other handle types. |

||||||||||

| Anse |  Handle, but most often referring to a D-shaped handgrip projecting from a broad baseplate. This is the style of handle you see on a heavy pan like a rondeau or stockpot, or as a helper handle on a big sauté. Because the handle only projects a few inches away from the pan’s body, it tends to heat up during cooking, particularly if it’s made of brass (as the majority are). See poignée for other handle types. Handle, but most often referring to a D-shaped handgrip projecting from a broad baseplate. This is the style of handle you see on a heavy pan like a rondeau or stockpot, or as a helper handle on a big sauté. Because the handle only projects a few inches away from the pan’s body, it tends to heat up during cooking, particularly if it’s made of brass (as the majority are). See poignée for other handle types. |

||||||||||

| Atelier | “Workshop,” but in a way that also conveys special respect for design and craftsmanship. | ||||||||||

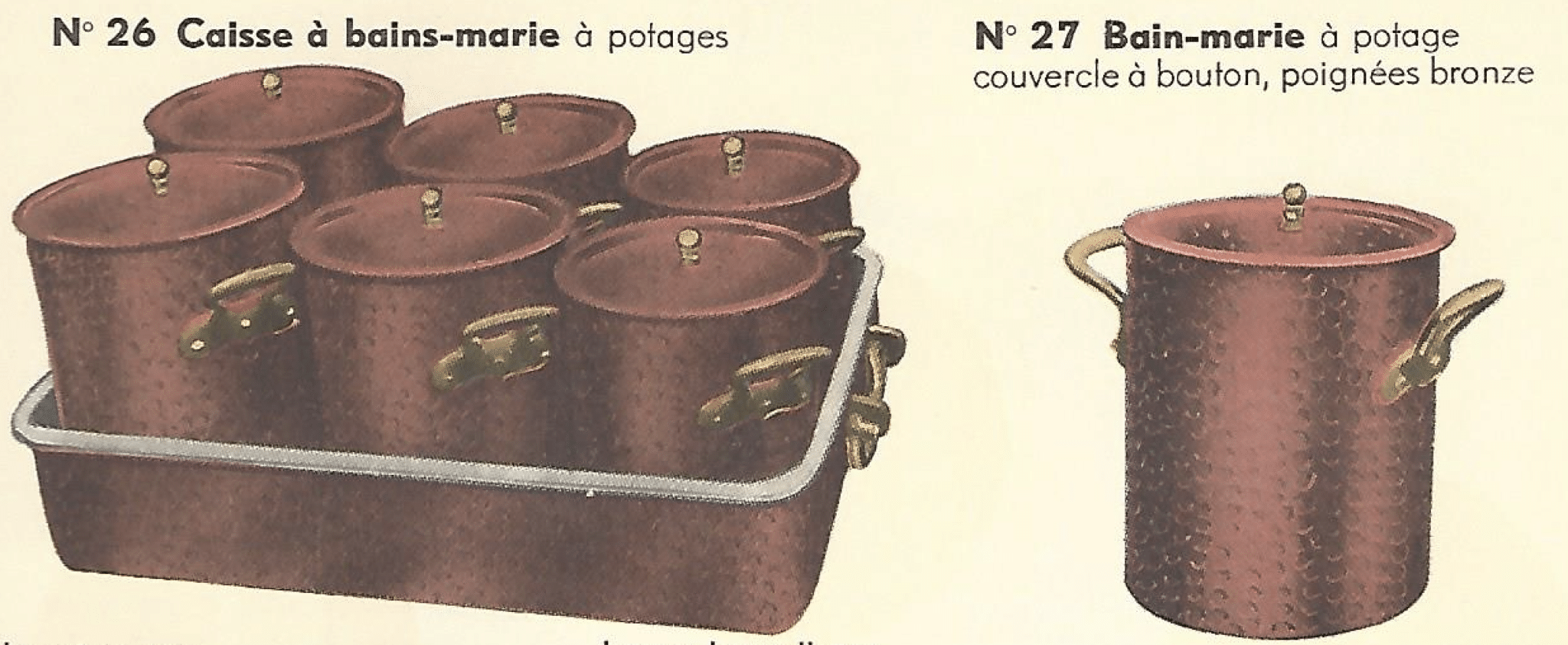

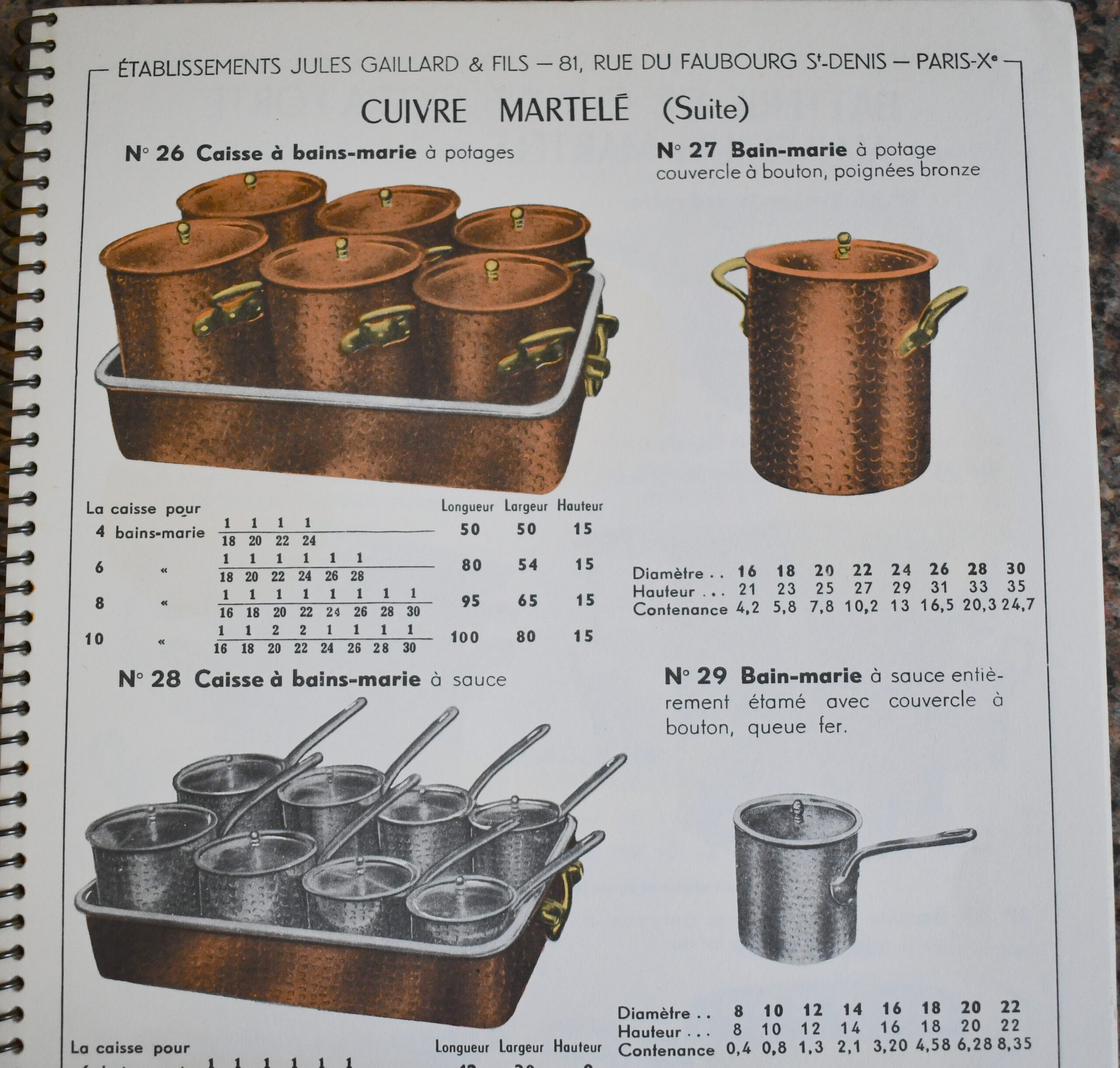

| Bain à potage |  Technically, a pot for warming soup (potage) in a heated water bath (bain), but for modern kitchens, the pot is used by itself on the cooktop. The tall narrow shape helps heat liquid without exposing too much surface area that would evaporate moisture. See bain marie below. Technically, a pot for warming soup (potage) in a heated water bath (bain), but for modern kitchens, the pot is used by itself on the cooktop. The tall narrow shape helps heat liquid without exposing too much surface area that would evaporate moisture. See bain marie below. |

||||||||||

| Bain marie |  A double-boiler, which is a cooking vessel set within a larger water-filled pot or pan. The purpose of a double-boiler is to apply steady heat to the inner cooking vessel without overheating it: the temperature of the outer water-filled pot cannot exceed 212°F/100°C, and so the inner vessel is heated to the same temperature without direct exposure to the heat source. A bain marie is useful for warming delicate sauces that could be curdled or “broken” if they get too hot, or for holding a soup or sauce at a steady temperature for a long period of time with no risk of scorching, even if you’re too busy to stir it. A double-boiler, which is a cooking vessel set within a larger water-filled pot or pan. The purpose of a double-boiler is to apply steady heat to the inner cooking vessel without overheating it: the temperature of the outer water-filled pot cannot exceed 212°F/100°C, and so the inner vessel is heated to the same temperature without direct exposure to the heat source. A bain marie is useful for warming delicate sauces that could be curdled or “broken” if they get too hot, or for holding a soup or sauce at a steady temperature for a long period of time with no risk of scorching, even if you’re too busy to stir it.

A present-day bain marie usually looks like two pots stacked on top of each other. Usually the inner vessel is made of white porcelain that sits on top of a narrow copper pot that’s filled halfway or so with water. According to Jean-Claude Renard, the name comes from the Latin word maris, meaning seawater. Alchemists discovered that salty water evaporated more slowly than fresh water and made a better liquid for the water bath because it didn’t need replenishing as frequently as did fresh water. (The French pronunciation of maris sounds exactly like “marie.”) M. Renard adds that bains marie à jus were tinned inside and out to protect the copper from the salt water. You can sometimes find antique and vintage bain marie pots with traces of old external tinning lingering around the handle. Finally, a recent piece of information: According to Urbain Dubois and Émile Bernard writing in La cuisine classique in 1856, one key function of the bain-marie à sauce was to warm up plated portions during a lengthy service à la française: “It is still necessary to have sauces in reserve in the caisse à bain marie at the place where they are being portioned, and to sauce the dishes as they are placed on the plates and the butlers distribute them.” |

||||||||||

| Bassine à ragoût |  “Basin for stew,” or stewpot. This pot is about half as tall as it is wide, so that from the side it looks rectangular. (Imagine stacking two rondeaux on top of each other — that would be like a stewpot.) “Basin for stew,” or stewpot. This pot is about half as tall as it is wide, so that from the side it looks rectangular. (Imagine stacking two rondeaux on top of each other — that would be like a stewpot.) |

||||||||||

| Bouton | “Button,” a knob handle on the lid of a pot. See poignée. | ||||||||||

| Braise | Literally, “ember,” meaning a hot coal of a wood- or coal-burning hearth into which pots were nestled for long slow cooking at a moderate temperature. This term is now used as a verb to refer to the cooking method and the vessels designed for it, but you may still see the phrase sur la braise in pre-20th century French recipes. Not to be confused with braze, a metal joining technique using brass as a filler. | ||||||||||

| Braisière |  A box-like pan with a tight-fitting lid and a side-mounted projecting handle. The handle enables the pot to be pushed deep into the hot coals — braises — of an open cooking fire. A box-like pan with a tight-fitting lid and a side-mounted projecting handle. The handle enables the pot to be pushed deep into the hot coals — braises — of an open cooking fire.

You’ll see the terms braisière and daubière used interchangeably, but my research suggests that technically they refer to the same type of pan at different historical periods. The braisière is from the era of open hearths, and so it has long handles to help the cook push it into the heat and then pull it out again. The daubière is a redesign for the enclosed ovens that began to appear towards the end of the 19th century, so it has close-set handles so it can more easily slide into an enclosed space. |

||||||||||

| Braze, brazing | A metal joining technique that uses a filler metal to seal the seam. The filler metal is melted and flowed into the crevices of the seam, where it bonds with the metal to seal the join. The best brazing metal is an alloy of the metals to be joined so that the filler forms a strong bond, but brazing can also work to join two different metals together.

The jagged yellow lines you see running around the base and up the side of an old copper pot are brazed joins called cramp seams (colloquially, dovetails) that use brass as the filler metal. Brass makes a great brazing metal for copper because it is an alloy of copper and therefore readily forms a bond to strengthen the join. Dovetails are still practiced to this day but have been replaced by welding for mass production. The difference between brazing and welding is that welding melts the edges of the metal pieces and fuses them together, whereas brazing only melts the filler. (This means that welding can only join two similar metals — they have to be able to fuse together.) The difference between brazing and soldering is the filler metal: while both techniques melt the filler into the join, soldering uses a filler that melts at a relatively low temperature. Solder is easier to work with but doesn’t produce as strong a join as brazing. Not to be confused with braise or braising. |

||||||||||

| Bronze | In French this word means bronze, of course, but there is an element of confusion (so to speak) in its use. Bronze — the alloy of copper and tin — has been smelted since antiquity, and for centuries the French used bronze indiscriminately for any copper alloy regardless of its actual chemical composition. It was not until the 19th century that metallurgists could purify zinc and add it to copper to produce brass (laiton), but the use of the term bronze has persisted and is often mistranslated to the English “bronze” without considering if the material is actually brass.

This misnomer continues to this day in Mauviel’s product literature and you will often see cookware with “bronze” handles that are actually brass. |

||||||||||

| Cafétiere | A coffeepot, usually a flat-bottomed receptacle to serve prepared coffee. | ||||||||||

| Casserole | “Pan,” the deceptively simple French term for a cylindrical pot or pan with a projecting stick handle. Today the word is used to refer to a saucepan or sauté pan, but the casserole predates both and is perhaps the earliest type of handled cookware formed from metal. According to Dehillerin,

No doubt [the casserole] first took form as a shallow bowl made much more useful with the addition of a projecting handle. That may in fact be the origin of its name. The word comes from casse or cassette — a large spoon or ladle. What today is commonly called a casserole is technically a casserole russe. The difference is in the proportions: a historical casserole is halfway between a sauté pan and a saucepan. It stands out to the modern eye because it doesn’t look quite right: we know the shallow sauté pan shape, and we also know the boxy saucepan shape — the historical casserole was somewhere in between.

The historical casserole seems to have been a common pan shape in the 19th century but fell out of favor in the 20th, squeezed out between the sauté and the taller russe. Today you’ll see casserole used to describe almost any stovetop pan and I don’t think it’s worth getting exercised about it. But I think the history is worth knowing! For more on the original of the casserole russe, please see service à la russe below. |

||||||||||

| Casserole à glacer |  “Glazing pan.” This is a sauté pan or saucepan with a tight-fitting cap-style lid (couvercle emboîtant). The chef used this pan to cook food brushed with gravy — glace, or glaze — and the lid keeps moisture inside, like a mini braising pan. “Glazing pan.” This is a sauté pan or saucepan with a tight-fitting cap-style lid (couvercle emboîtant). The chef used this pan to cook food brushed with gravy — glace, or glaze — and the lid keeps moisture inside, like a mini braising pan. |

||||||||||

| Casserole russe | See russe below. | ||||||||||

| Chaudron | “Cauldron,” but also colloquially “boiler,” as in a hot-water heater. | ||||||||||

| Chaudronnerie | “Cauldron making,” referring colloquially to industrial metalworking as well as the firm that does it. In pre-industrial France, a chaudronnerie made large copper vessels for holding and heating water, such as for home plumbing and heating; the firm’s skills were to forge large sheets of copper and then shape and join them into large containers. There was some overlap between chaudronnerie and poêlerie — making cooking pots — but poêlerie entailed extra steps to balance the item that were unnecessary for chaudronnerie. An 18th or early 19th century metalworking business would specify whether it was a chaudronnier, poêlier, or both.

The industrial revolution in the mid-19th century produced machine tools that enabled consistent perfection at much greater speed, and most poêliers abandoned the old hand techniques in favor of rolling mills, presses, and powered lathes. Though they still created cooking pots, their use of machine tools made them chaudronniers. |

||||||||||

| Chaudronnier | “Cauldron maker,” or boiler-maker. While I (and others) use this term indiscriminately for any coppersmith, technically it refers to one who makes industrial items — boilers, hot water systems, et cetera. A pan-maker was more correctly termed a poêlier. | ||||||||||

| Cocotte | A round or oval pan with a well-fitting lid, equivalent to a modern-day dutch oven. Sometimes cocotte is used generically for any lidded pot with short handles. | ||||||||||

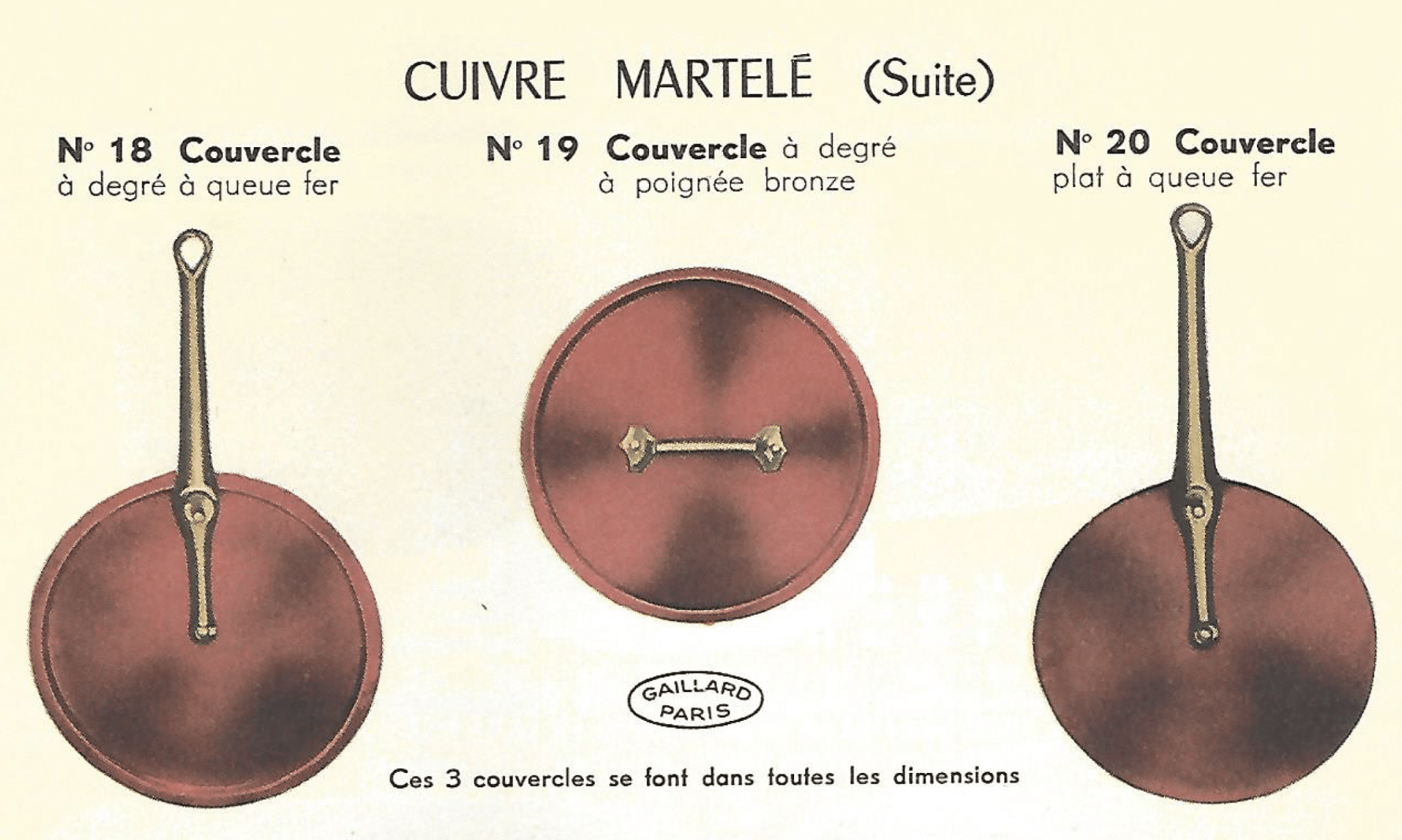

| Couvercle | “Cover,” meaning the lid to a pot or pan. French pots and pans have all manner of closing mechanisms to manage heat and moisture retention for cooking and serving, and there are specific sub-types that warrant definition and explanation.

|

||||||||||

| Cramp seam | A metal joining technique that interleaves thin layers of copper, pounds them together, and seals the join with brazing. Cramp seams were used to assemble copper cookware prior to the development of industrial welding in the early 20th century. Cramp seams are colloquially called dovetails. | ||||||||||

| Cuivre, cuivre rouge, cuivre jaune | Copper. It bonds so readily with other metals that early smiths could form a wide range of copper alloys without fully understanding their chemical composition. As they smelted copper they described the alloys by color: cuivre rouge, “red copper,” has high copper content (up to and including pure copper) and is noticeably red; cuivre jaune, “yellow copper,” was copper mixed with calamine (that is, zinc) to make brass, properly termed laiton.

I sometimes see pots described as cuivre jaune that are more likely brass. |

||||||||||

| Cuivralec | Copper lined with aluminum. Trademark of L. Lecellier in Villedieu. | ||||||||||

| Cul de poule | Literally, this means the, uh, nether regions of a chicken. In French cuisine, this term refers to a large bowl sized for whipping quantities of eggs, cream, or sauce for whatever delicacy was in store. It is perhaps typically and perfectly French that mountains of frothy white egg whites should be produced from a “chicken’s butt.” | ||||||||||

| Cunilec | Copper lined with nickel. Trademark of L. Lecellier in Villedieu. | ||||||||||

| Cupretam Cuprinox Cupronil |

Three brand names used by Mauviel in the 1980s-1990s to refer to copper cookware with different linings: Cupretam with tin, Cuprinox with stainless steel, and Cupronil with nickel. See here for more. | ||||||||||

| Daube | “Stew,” one large piece of meat or large chunks marinated in and/or cooked with wine in the sauce. Traditionally, a daube is a specific Provençal style of stew, while a braise refers to the general cooking method. Strictly speaking, all daubes are braises, but not all braises produce a daube; that said, in the present day, the two terms are often used interchangeably. (Technically, a daube is distinct from a ragoût in that a daube incorporates wine in the recipe while a ragoût does not.) | ||||||||||

| Daubière |  A rectangular or oval pot that looks like a box, intended for cooking braises or stews. A daubière is named for the daube, a type of stew. Éscoffier and other august sources claim that a daubière is only ever properly made of earthenware, but I suspect this arose from a now-obsolete health issue: in the 18th and 19th century, tin linings were sometimes adulterated with lead, and the wine-rich recipes of many daubes resulted in leaching and discoloration. The pure tin that is now used does not carry this risk and a tinned copper daubière is as safe as an earthenware one. (I have a post on cooking with a daubière.) A rectangular or oval pot that looks like a box, intended for cooking braises or stews. A daubière is named for the daube, a type of stew. Éscoffier and other august sources claim that a daubière is only ever properly made of earthenware, but I suspect this arose from a now-obsolete health issue: in the 18th and 19th century, tin linings were sometimes adulterated with lead, and the wine-rich recipes of many daubes resulted in leaching and discoloration. The pure tin that is now used does not carry this risk and a tinned copper daubière is as safe as an earthenware one. (I have a post on cooking with a daubière.)

The lid is always a fitted couvercle emboîtant to create a good seal to keep moisture inside. A lid with a vertical rim was intended to hold hot coals or water to assist with the cooking process; a lid with a slight indentation helped catch and direct condensate back into the dish instead of leaking out around the edge of the lid. |

||||||||||

| Deep-drawing | The industrial technique of forming a deep metal vessel by pressing a sheet of metal around a form. See emboutissage. | ||||||||||

| Dinanderie | A brass-works. Many copper pots have brass handles, and some copper manufacturers maintained an in-house brass-works to cast them. The term comes from the Belgian town of Dinant, a center of brass-working since the Middle Ages. | ||||||||||

| Dovetail | The common term (and misnomer) for a cramp seam, a metal joining technique that interleaves thin layers of copper, pounds them together, and seals the join with brazing. Dovetails were used to assemble copper cookware prior to the development of industrial welding in the early 20th century. | ||||||||||

| Dutch oven | This is not a French term, of course, but I am a word nerd and I can’t help myself when it comes to correcting common etymological misconceptions: The “dutch oven” was not invented by the Dutch people of the Netherlands. The word “dutch” in this context means cheap or fake, as in, if you don’t have a real oven, you can use a dutch oven on the stovetop instead. (It’s a related concept to “going dutch” on a date, meaning that each person pays the bill for him or herself instead of one person generously paying for the other.) This pejorative term goes back to 17th century England during fierce military and economic competition with the Netherlands.

In any event, a dutch oven is a stovetop cooking vessel with a well-fitting lid that creates a warm moist space to braise food. The closest equivalent French terms are the cocotte and the four de campagne. |

||||||||||

| Écumoire | Skimmer, referring to a square or rectangular piece of copper punched with holes and mounted on a long handle. This was how fat was skimmed from stock as it simmered in a stockpot. | ||||||||||

| Emboutissage | The French term for deep-drawing, the manufacturing technique of using a powerful press to force a piece of metal into shape around a form. This is the modern process to form deep pots such as saucepans, stewpots, stockpots, and the like. The French consider this technique to be industrial chaudronnerie, whereas poêlerie would accomplish the same thing by hammering or piecing the pot together by hand.

|

||||||||||

| Étain Étamé Étamage |

Étain is the word for tin. Étamé refers to something that has been lined with tin; étamage is the process of applying a tin lining. | ||||||||||

| Fait tout or faitout | “Does everything,” referring to a pan capable of a range of cooking tasks. In the 19th century this referred to any wide and shallow pan with two side handles. In the present day, this term is used for all sorts of pans, such that you can’t really tell which one is meant just by the term. | ||||||||||

| Fer | Iron. | ||||||||||

| Fer blanc, ferblanterie | Tin, tin-plating. These are archaic French terms: fer blanc literally means “white iron,” and I can’t tell whether this refers to iron that has been coated with tin, or whether the term comes from the time when smiths mistook tin for a whiter variant of iron. In any event, a ferblanterie is a business that works with tin to coat or plate other metals. | ||||||||||

| Gratin | A French cooking method where food is prepared with a cheese sauce and covered in breadcrumbs and baked in an oven. A gratin pan is usually wide and shallow so that food can be spread out for maximum crisping. Gratin pans can be round or oval, with stick, loop, or ring handles. | ||||||||||

| Huguenote |  An archaic French term for a shallow round pan made of earthenware or copper with a well-fitted lid. It could be set flat on the floor of the hearth or, when fitted with short iron feet, would sit low above the coals. An archaic French term for a shallow round pan made of earthenware or copper with a well-fitted lid. It could be set flat on the floor of the hearth or, when fitted with short iron feet, would sit low above the coals.

The name comes from the Huguenots, a Calvinist sect of French Protestants who were persecuted by the government of France from the 16th century until the Edict of Versailles in 1787. When the Huguenots defied the Catholic fasting days, they cooked meat in this squat little pan hidden deep within the hearth. This recipe for oeufs a la huguenotte is dated 1643 by “LSR” in L’art de bien traiter and it sounds pretty good: Put in a dish a glass or two of good beef jus, or mutton jus mixed with some mushroom jus, if you have any, with a small morsel of good fresh butter; break in a reasonable quantity of eggs, and in proportion season the yolks with salt and white pepper, with nutmeg if you like it; cover everything for a while, because it must cook quickly; after which you will serve it warm, coated with a few spoonfuls of your best accompaniments. I think the huguenote is functionally the same as a tourtière. |

||||||||||

| Inox | Short for inoxydable, “cannot be oxidized,” referring to stainless steel. You may see INOX stamped on cookware (and other items) to specify that it’s made of stainless steel. | ||||||||||

| Laiton | Brass. I suspect this French term is related to the archaic English term latten that was used from the Middle Ages to the 19th century to refer to all copper alloys (brass or bronze) before techniques developed to detect the component elements and control their precise proportions in the alloy. (I wonder if this is the origin of the present-day confusion between brass and bronze handles.) | ||||||||||

| Lanter, lantoux | In traditional French poêlerie, lanter is the archaic French term for the process of hammering finished copper pieces with an intentional surface pattern to even out the appearance, and the person who does it is a lantoux. | ||||||||||

| Lollipop lid | A pot lid made from a disk of metal riveted to a long skinny piece of iron or brass that serves as the handle. This is definitely not a French term, but any reasonable person must concede that if one holds such a lid straight up that yes, it does look like a lollipop. | ||||||||||

| Louche | A ladle or dipper — a small copper cup at the end of a long handle. In some cases these come in sets labeled by volume, serving as early measuring cups that were dipped into a pot or bowl of liquid. | ||||||||||

| Manche | “Sleeve,” referring to a tubular handle. See poignée. | ||||||||||

| Marmite |  The French term for a cylindrical pot that is as tall as it is wide — what we call a stockpot. According to Dehillerin, The French term for a cylindrical pot that is as tall as it is wide — what we call a stockpot. According to Dehillerin,

The word “marmite” appears in the 12th century in the French language to describe the contents simmering under the lid. As wide as it is tall, cylindrical in shape and equipped with two side handles, it has a lid, unlike the cauldron that it replaces. Just like the faitout (shorter), the rondeau, the huguenote (on feet) and the pot-au-feu (taller), it is part of the “vessels of cooking,” these large containers that appear after the Revolution. Allegedly, the British product Marmite got its name because it was packaged for the long journey to Australia in a marmite. |

||||||||||

| Marmite traiteur | “Catering stockpot,” another term for stockpot, usually meaning the really big ones. | ||||||||||

| Martelage | “Hammering,” but I will use it on this site to refer to an intentional pattern of hammer (martel) marks on the exterior of a copper pot. | ||||||||||

| Mitraille | An archaic term for chunks of recycled copper and brass that dinandiers and poêliers collected, purified, and reforged to make new pots. (The word technically means grapeshot, itself referring to round lumps of undifferentiated metal that could be loaded into a musket.) | ||||||||||

| Mousseline | A stick-handled, bowl-like pot with a flat base that is a convenient shape for beating and whipping liquids, such as egg whites and cream to make a mousse. Similar to a sauteuse bombée. | ||||||||||

| Oreilles | “Ears,” referring to small tab handles, the kind you see on charlotte molds and Pommes-Anna pans. See poignée. | ||||||||||

| Pan de truite |  A “trout pan,” technically a short poissonière, designed to poach smaller varieties of fish without folding or tearing the flesh. The pan is narrow, usually about a foot long or less, with a domed lid. A perforated metal platform with lifter handles fits inside the pan onto which the fish and accompaniments can be lowered for cooking and then raised out without trauma. A “trout pan,” technically a short poissonière, designed to poach smaller varieties of fish without folding or tearing the flesh. The pan is narrow, usually about a foot long or less, with a domed lid. A perforated metal platform with lifter handles fits inside the pan onto which the fish and accompaniments can be lowered for cooking and then raised out without trauma. |

||||||||||

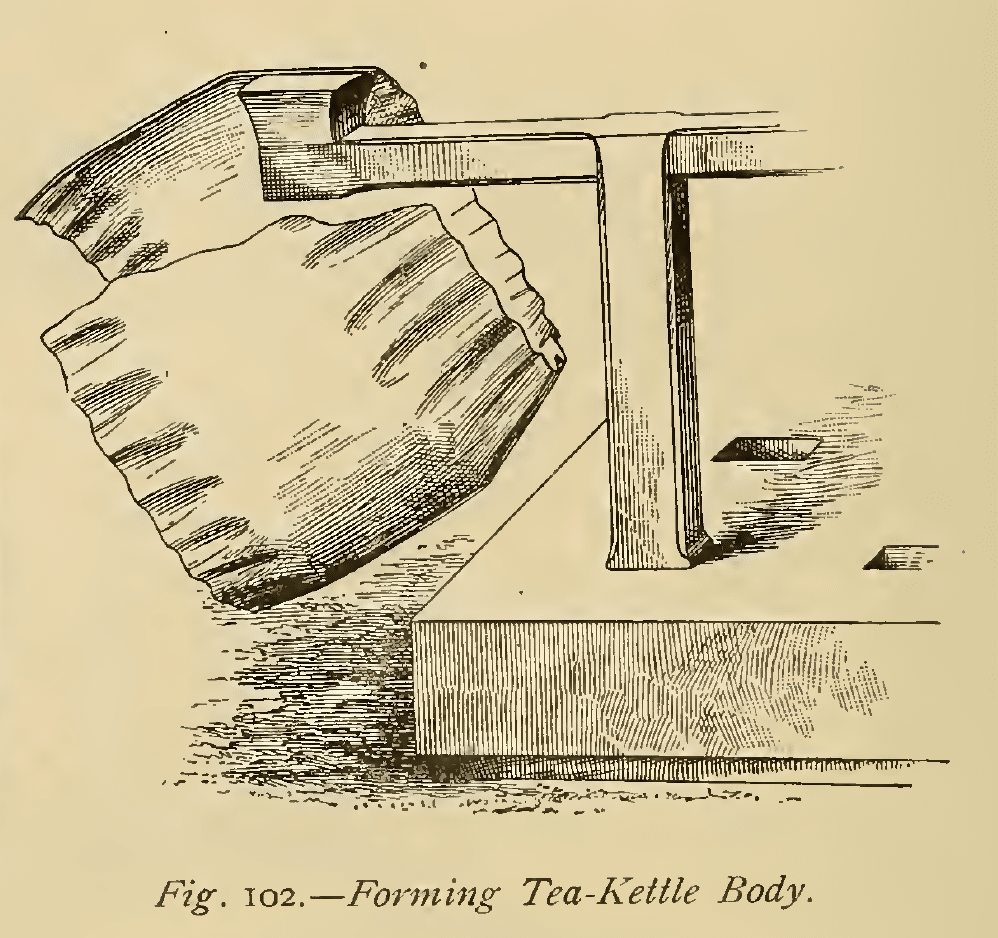

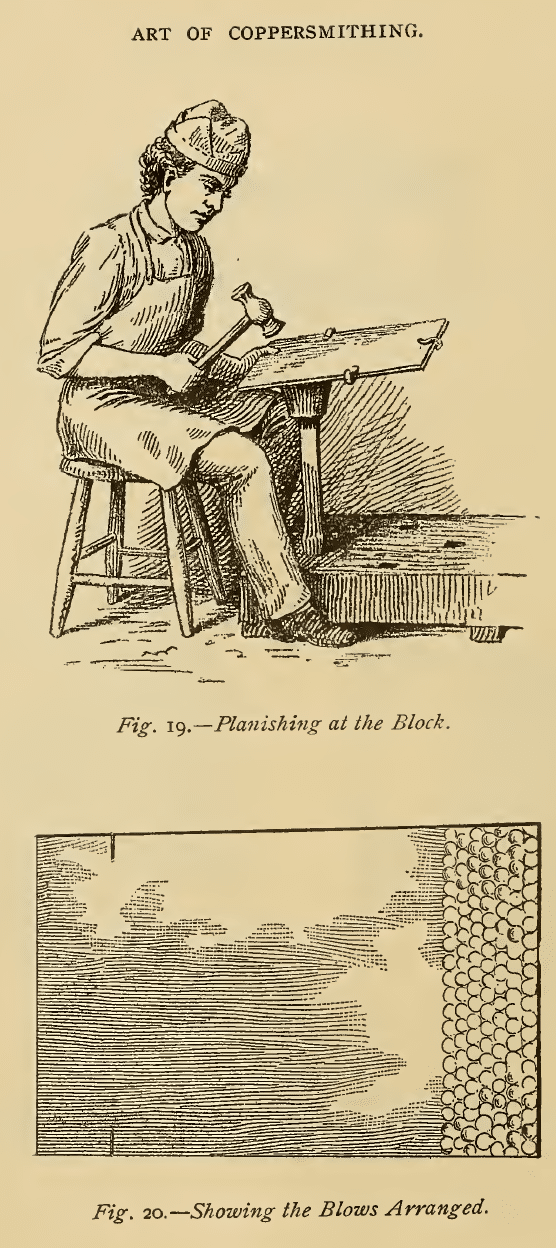

| Planishing | The act of applying pressure to metal to shape, smooth, and harden it. Copper can be planished prior to shaping by running sheets through rollers, or by hand with a planishing hammer. John Fuller’s 1893 book “Art of Coppersmithing” describes the various purposes of hand-planishing:

Planishing as understood by braziers is the art of first molding smoothly or shaping the metal when first formed; second, hardening or closing the grain, and third, by the aid of the hammer giving it a gloss or a kind of case-hardening sufficient to receive the final polish with tripoli, which is a very fine powder having a purple hue. That “hardening or closing the grain” step was a crucial one. Just as do the atoms of any metal, copper atoms align into crystalline structures (or “grains”) as the metal cools from smelting; the larger the crystals, the more malleable and ductile the copper. Planishing crushes larger grains to form smaller ones and renders the copper more resistant to dents and deformation. (This is also called “work hardening” — the metal is hammered, or worked, in order to increase its hardness and resilience.) According to Fuller, apprentices were taught how to wield a planishing hammer by working on flat sheets of copper. The trick was to learn how to lay down even rows in a methodical way without overlapping:

[T]he sheets are then taken to the large bottom-stake (Fig. 19), and with a suitable hammer, called a bottom-hammer, which has one face a little fuller in the center than the other, the pieces are planished — that is, the grain of the copper is closed. There is only one way to do this part of the work successfully and in a perfect manner, and there is a little knack in it… The secret of success is to keep the blows regular. The best results are obtained by striking each succeeding blow as near a direct line with the previous one as possible, and then filling in between as each line is completed, as in Fig. 20.

While he is engaged at this many a “half-moon” intrudes itself on the surface of his work to enlighten him that he must be careful and attend to his task. Planishing is sometimes confused with martelage. The difference is that planishing is the general term for pressure (or impact force) to create a uniform surface, while martelage is a final round of hammering applied to machine-pressed pieces to add additional work hardening, leaving a distinctive multifaceted appearance. |

||||||||||

| Plat à sauter | Sauté pan. See sauté. (On this site, I am adopting this term to refer to a two-handled sauté pan — an archaic pan type from the 1880s or so, replaced by the stick-handled sauté and the rondeau.) | ||||||||||

| Poêle | “Oven” or “stove,” referring both to a skillet as well as to a modern wall oven. I was curious as to why the French have one word for things that in English are very different concepts, so I looked into the history.

In archaic French, the poêle was the simplest possible vessel to cook food: a resilient container that could be put close to a heat source. In 14th century France — the earliest written record of the use of the word — a poêle was a long-handled skillet-like pan with a fitted lid that was pushed deep into the embers of a fire; a poêlier was a person who could craft these small containers from metal with the skill to shape and balance them so they could be handled easily. As technology advanced, the cooking fire was enclosed in a bricks (a primitive stove called a potager) and then inside a stove — that is, a metal enclosure heated with wood or coal to create a hot surface on top. This made possible many more shapes of poêle such as the casserole, rondeau, sauteuse, et cetera. Then came the modern oven, a cavity around which heat could be produced on demand — a poêle fixed into place. As above, the word poêle is used in the present time to refer to wall ovens as well as to hand-held pans, but by convention only to the skillet (or frying pan) shape, as other shapes of pan have been given their own specific names. (Ironically, the English term “skillet” is itself derived from the French term écuelle, or bowl.) Another common term you will see with archaic origins is casserole, allegedly derived from the medieval French term casse or cassette (spoon). |

||||||||||

| Poêlerie | Literally, “oven-making,” but colloquially the fine hand-work of shaping and balancing pots and pans, referring both to the practice and the business that does it. Traditional poêlerie entailed forging and cutting sheet copper and then shaping and balancing copper pots by hand. Towards the end of the 19th century, poêliers began adopting industrial machine tools — rolling mills, presses, and lathes — to work with sheet copper, thereby becoming chaudronniers. | ||||||||||

| Poêlon | A sugar pan — a small saucepan with a tubular metal handle (manche) and a spout, usually unlined, for boiling sugar for caramel and other confectionary. | ||||||||||

| Poignée | Handgrip. Used on its own, poignée usually refers to a simple bar or half-circle handle riveted at each end. However, as with other crucial elements of French cookware, there are sub-types of poignée with specific names.

|

||||||||||

| Poissonière | A long narrow pan with a fitted lid designed to poach larger varieties of fish without breaking the delicate flesh. A poissonière comes with a perforated metal platform with handles that fits inside the outer copper pan and can be lifted out, helping to ensure that the fish stays in one piece for a more pleasing presentation on the plate. Unfortunately many vintage poissonières have parted ways with their lifters, so if you find an intact set, cherish it. | ||||||||||

| Pommes-Anna |  A low round pan with a close-fitting cap-like lid (couvercle emboîtant) and short stubby handles on the sides of the pan and lid that look like ears (oreilles). This pan is named for the dish pommes Anna, a potato dish that is flipped over during the cooking process. The lid of a pommes-Anna pan is designed to fit tightly over the base and the short ear-like handles to align perfectly so they can be grabbed together; this makes it easier to invert the pan during the cooking process without the halves coming apart or liquid leaking out. A low round pan with a close-fitting cap-like lid (couvercle emboîtant) and short stubby handles on the sides of the pan and lid that look like ears (oreilles). This pan is named for the dish pommes Anna, a potato dish that is flipped over during the cooking process. The lid of a pommes-Anna pan is designed to fit tightly over the base and the short ear-like handles to align perfectly so they can be grabbed together; this makes it easier to invert the pan during the cooking process without the halves coming apart or liquid leaking out. |

||||||||||

| Pot | “Pot.” Strangely, this simple French word — pronounced “poe,” as in Edgar Allen — seems not to be used very frequently in reference to cookware. Instead, casserole seems to be the generic term for a cooking pot. | ||||||||||

| Pot-au-feu | “Pot on the fire,” or stew, once again referring to the dish itself and also the vessel within which it is cooked. As a dish, pot-au-feu is a traditional French family meal of meat, vegetables, and herbs in water or stock, cooked for hours to produce a simple and savory dinner.

As a vessel, the pot-au-feu is a round or oval pot with lid similar to a cocotte or dutch oven that can be placed right up inside the fire (au feu). Sometimes a pot-au-feu has a cap-style couvercle emboîtant with a vertical rim where more hot coals can be piled to help keep it hot. (Anecdotally, I have read that the name of the Vietnamese dish phở — pronounced “fuh” — was adapted from the feu in pot-au-feu.) |

||||||||||

| Queue | “Tail,” referring to a thin projecting stick handle, often with a hanging loop at the end. See poignée. | ||||||||||

| Ragoût | A stew with small- to medium-sized chunks of meat or fish. Traditionally, a ragoût does not incorporate wine, which distinguishes it from a daube, which does. | ||||||||||

| Raise, raising up | In metalworking, the act of hammering a flat sheet of metal to shape it. Often used as “raising up” to connote the transformation from a flat sheet to a three-dimensional object.

Not to be confused with razing, a technique to curve sheet metal. (For non-English speakers, please note that the words “raise” and “raze” sound exactly the same in English.) |

||||||||||

| Raze, razing down |  In metalworking, the act of curving flat sheet metal by “wrinkling” it into a series of flutes and then hammering the flutes flat. In metalworking, the act of curving flat sheet metal by “wrinkling” it into a series of flutes and then hammering the flutes flat.

As the 1911 edition of the Encyclopedia Brittanica explains it, If a circular disk is wrought into a hemisphere and the attempt is made to hammer the edges round, crumpling must occur. This in fact is the first operation, termed wrinkling, the edge showing a series of flutes. These flutes have to be obliterated by another series of hammerings termed razing. The result is that the object assumes a smooth concave and convex shape, without the thickness of the metal becoming reduced. Often used as “razing down” to connote the closing of the shape. Not to be confused with raising, a general term for hammering sheet metal into shape. (For non-English speakers, please note that the words “raze” and “raise” sound exactly the same in English.) |

||||||||||

| Repoussage | The French term for spinning, which is the process of mounting a piece of metal on a lathe, rotating it, and shaping it against a form called a mandrel. This is the modern metalworking technique for making symmetrical pieces like skillets, bowls, vases, teapots, et cetera. The French consider this technique to be industrial chaudronnerie as opposed to poêlerie which would shape the piece by hand with a hammer.

|

||||||||||

| Rondeau or rondin |  A shallow round pan with two handles mounted on the sides. There is no fixed definition for the dimensions of a rondeau, but my observation is that a rondeau is generally one-third as tall as it is wide. A shallow round pan with two handles mounted on the sides. There is no fixed definition for the dimensions of a rondeau, but my observation is that a rondeau is generally one-third as tall as it is wide. |

||||||||||

| Russe | A cylindrical pan almost as tall as it is wide — what in the present day we consider a saucepan. Most modern French sources use the catch-all term casserole for saucepans of these proportions, but traditionally the russe was specialized for restaurant use while a casserole was shorter, more like a small-scale sauté pan. Many professional kitchens to this day use the word “russe” (rhymes with “loose”) to refer to saucepans.

For the origin of the term, please see service à la russe below. |

||||||||||

| Saucier | “Sauce-making pan,” referring to the humble saucepan, a short cylindrical pot with a stick handle, where the body of the pot is not quite as wide as it is tall. Sauce pans are the workhorses of traditional French cooking. | ||||||||||

| Sauté |  Literally, “jumped,” and colloquially in French cuisine referring to a round pan that is wider than it is tall and fitted with a stick handle or, in its more archaic form, two side handles. (You may also occasionally see a sauté pan called a sauter or plat à sauter, “pan to jump.”) Literally, “jumped,” and colloquially in French cuisine referring to a round pan that is wider than it is tall and fitted with a stick handle or, in its more archaic form, two side handles. (You may also occasionally see a sauté pan called a sauter or plat à sauter, “pan to jump.”)

The sauté pan got its name for its suitability to jump food — that is, to agitate the pan so that the food turns over and mixes with oils and flavorings and cooks evenly. The straight sides of the sauté pan are helpful to keep things in the pan so they don’t actually jump out of the pan itself. |

||||||||||

| Sauteuse | A sauté pan whose walls are not vertical — that is, they are rounded (sauteuse bombée) or straight but set at a slant (sauteuse évasée). | ||||||||||

| Sauteuse bombée |  A “domed” sauté pan, meaning it is shaped like a flat-bottomed bowl. Similar to a mousseline. A “domed” sauté pan, meaning it is shaped like a flat-bottomed bowl. Similar to a mousseline. |

||||||||||

| Sauteuse évasée |  A “flared” or splayed sauté pan, such that the pan is wider at the top than at the base. Also called a Windsor. A “flared” or splayed sauté pan, such that the pan is wider at the top than at the base. Also called a Windsor. |

||||||||||

| Sautoir | Another term for sauté. It is hinted that a sautoir refers to a sauté pan equipped with a lid so that it can also go into the oven. | ||||||||||

| Seau | “Bucket,” also used to refer to a cylindrical or ovoid container used to keep wine or champagne cool or to hold ice. A copper champagne bucket is gorgeous and works quite well, but be warned that its conductive walls trigger condensation, so put it on top of a tray or plate or something or it’ll leave water marks on wood. (Guess how I know this.) | ||||||||||

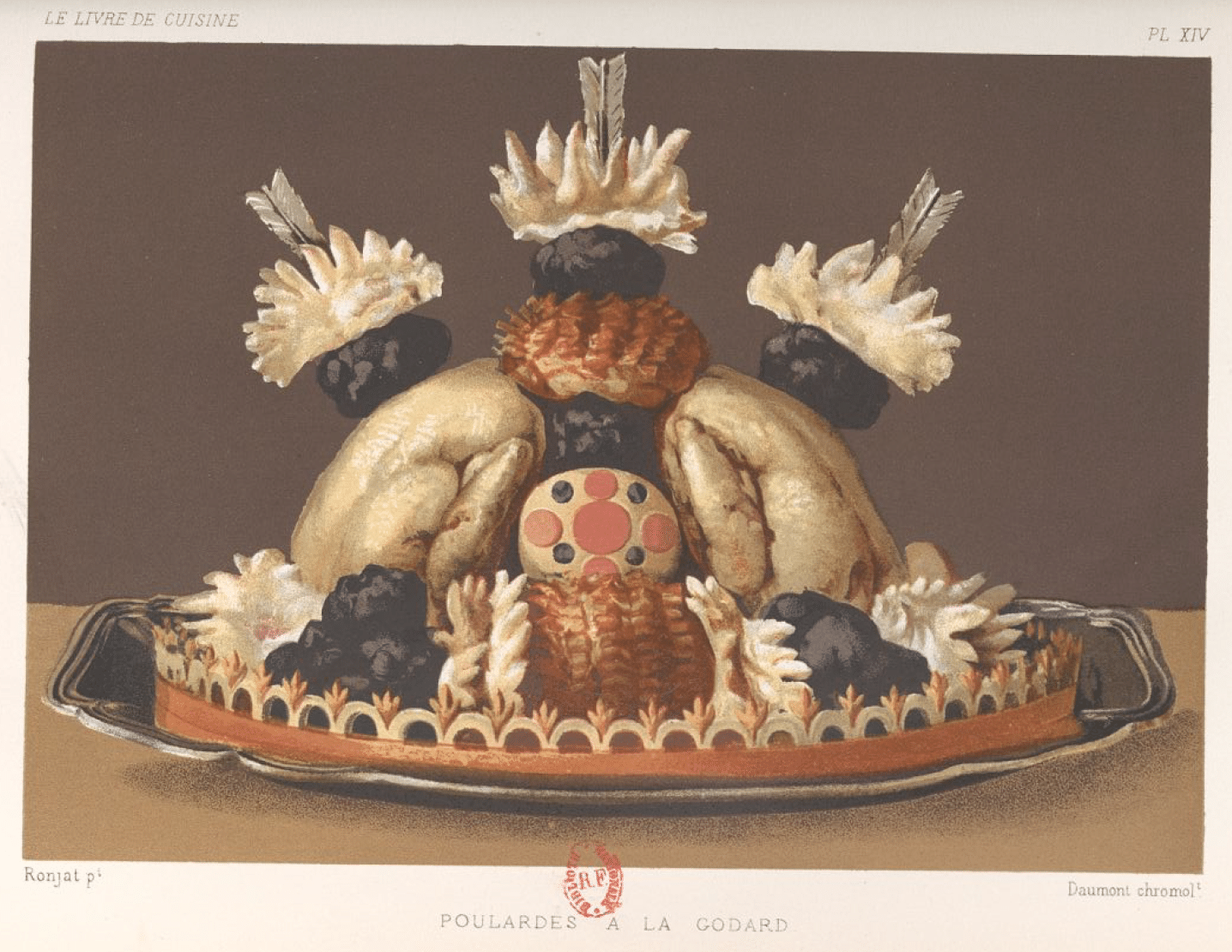

| Service à la française, service à la russe | These were the two styles of formal table service during the 19th and very early 20th century. Service à la française was the traditional formal French style in which the evening’s main courses were presented at once, arranged on platters, and then taken away to be divided into portions, plated, and served in sequence. This theatrical ritual emphasized the chef’s skill at creative presentation at the expense of leaving the food to cool to a tepid temperature during the length of time between presentation and serving. (I could not help but grab samples of these arrangements from Jules Gouffe’s 1867 Livre de cuisine.)

Service à la russe was an innovation introduced in 1810 by Alexander Kurakin, the Russian ambassador to France from 1808 to 1812. Kurakin hosted a grand dinner at his residence in Paris at which “the hot dishes were prepared one by one in the kitchen and then brought to the dining room to be presented by the hostess to her guests and served at a temperature chosen by the chef.” This innovation of successive courses became known as service à la russe and it demanded new logistics within the kitchen. Whereas service à la française prepared all the dishes in advance, presented them at the same time, and then portioned and served them, service à la russe entailed timing each course to be ready to eat in sequence and served at the optimal temperature. Tout Paris was captivated by this modern presentation style, but for a period of time there was a spirited debate over the merits of each method. The great chef Jules Gouffé, l’apôtre de la cuisine décorative (“the apostle of decorative cuisine”), waded into the fray in his 1867 book and applied his wisdom to chart a pragmatic middle path. For several years, there have been numerous disputes over the two types of service that have been called, far too exclusively in my opinion, one French-style and the other Russian-style: the first, which consists of serving on the table the courses of an entire service, which are then removed to portion them; the other which only presents courses portioned in advance, which are therefore very difficult to make presentable for the table other than in fragments reassembled by artifice oftentimes only somewhat successful. There is obviously good to be found as well as disadvantages with both methods. The Russian service is an incontestably more expeditious concept and simpler in practice than the old French service, whose confusions and infinite slowness have often been criticized with good cause; but one cannot deny also that this way of cutting up everything in advance tends to destroy the beautiful art of decoration and arrangement at which so many of our most famous masters have excelled. Is this not a slap in the face to our great French cuisine, that display of taste and flair that has contributed in no small part to its elevation to a higher plane over all other cuisines? On the other hand, it is indisputable that there is a very serious disadvantage in making certain dishes wait indefinitely on the table to lose their quality as they are left to languish. There are no warming trays or lids to hold their temperature; it is proven that many things, and some of the most popular dishes at that, should be eaten right when they come out of the oven. In this case, there can be no possible hesitation; it is quite clear that we cannot put on the table as a decoration that which cannot wait to be eaten: the question of the presentation of the food must be entirely sacrificed to that of its consumption. It therefore seems to me that when we have thus weighed the strengths and weaknesses of the two systems, there is no need to argue endlessly for one or the other; the choice is quite naturally indicated by practicality itself. Certainly nothing prevents serving on the table, as garnish and adornment as it should be, first all the large cold dishes, susceptible as they are to stimulate appetite and anticipation; also the big dishes, the hot starting courses, which can generally wait on a heating tray without wasting away. In this way, the guests, when they take their seats, will not be likely to find the table only decorated with fruits, compotes, gilded bronzes, vases of flowers, and other objects that by their nature are not nutritious and which would not produce the stimulating aperitif sensations required for the start of a grand and delicious dinner. But nothing prevents either serving on fleeting plates those things that need to be eaten at the moment and are especially intended for consumption without aiming to flatter the eye. We can thus manage to satisfy the appetites of the people we serve more promptly, and also leave time to cut the large courses without too much haste. I therefore maintain that a meal planned with this combination — the fusion of two systems — can but only give full and complete satisfaction to the cook who will have made it with these considerations. The guests will hardly inquire whether the service is more particularly French or Russian. What they will recognize, I dare say, is that the dinner presented to them fulfills the most essential points of the culinary art. The eyes, with which we also eat, as we have rightly said, will be satisfied by the appearance of the dressed dishes, and at the same time gourmets will be able to savor the more delicate products in the best conditions and, if I may say, the exquisite improvisations of true cuisine.

|

||||||||||

| Soldering | A metal joining technique that flows a filler metal between two metals to seal them together. Soldering is similar to brazing but at a lower temperature; solder is usually a soft metal or compound that melts easily but does not form a very strong join. Brazing, by comparison, uses a filler metal with a higher melting point to create a more resilient seal; the strongest join of all is a weld, in which the edges of the metal are melted and fused together with no filler at all. | ||||||||||

| Spinning | In the context of metalworking, this is the technique of creating a metal vessel by rotating a sheet of metal on a spindle and deforming it against a form called a mandrel. See repoussage. | ||||||||||

| Tourtière |  A round shallow pan with a well-fitting lid suitable for cooking a French tourte, a savory pie of meat and vegetables in pastry. A round shallow pan with a well-fitting lid suitable for cooking a French tourte, a savory pie of meat and vegetables in pastry.

This is a very old style of French pan, dating back at least to the 17th century (and likely much earlier). Early versions for hearth cooking have iron feet, but it could also be set directly into the coals. The lid is a fitted couvercle emboîtant with a recessed area to pile on hot coals to help with heat, similar to a braisière. The tourtière is functionally similar to the huguenote. |

||||||||||

| Welding | A metal joining technique that uses high heat to melt the edges of metal pieces so that they fuse together. The techniques for welding were discovered in the 1800s but it was not until the invention of the hand-held acetylene torch in France in 1901 that it became practical at an industrial scale. World War I accelerated the adoption of welding across the metalworking industry, and by the 1920s welding was the preferred method to join metals.

Welding produces the strongest joins between pieces of metal, but the metals have to be the same or similar enough to be able to fuse together. Brazing and soldering are joining techniques that use a filler metal that can bond different metals together, but the join itself is not as strong as a welded seam. |

||||||||||

| Windsor | Another term for a sauteuse évasée — a round pan with a conical profile wider at the top than at the base, with a stick handle. I’m trying to find out why this shape is called a Windsor and I have had no luck whatsoever. |

Sources

I am indebted to any number of Internet sites with cookware information, but my most useful resource on historical items and the intricate differences between vessels and tools is les Cuivres de cuisine by Jean-Claude Renard (ISBN 10: 2859172424, ISBN 13: 9782859172428). It was published in French in 1997 and it’s out of print, but Amazon and Abe Books usually have some used copies available. It’s marvelous.

I also direct you to Elizabeth David’s wonderful French Provincial Cooking (New York : Penguin Books, 1999; here it is on Google, and it’s still in print). She writes conversationally about regional recipes with descriptions of the appropriate cookware, conveying a fine sense of the distinctions between ostensibly similar items.

Couvercle plât, “flat cover,” a featureless disc capable of covering any pot of lesser diameter than itself. This is the pre-19th century lid style, though the concept persists to this day as a “universal lid.”

Couvercle plât, “flat cover,” a featureless disc capable of covering any pot of lesser diameter than itself. This is the pre-19th century lid style, though the concept persists to this day as a “universal lid.” Couvercle emboîtant: “Fitted cover,” meaning designed to slip down around the top of the pan like a cap. (Here the term takes the active –ant because it is encasing the pot beneath it.) These lids have a vertical flange running around the perimeter that fits closely to the body of the pan and creates a good seal to retain moisture during cooking. These are most commonly seen on box-shaped daubières and braisières, but when made for a round pan, the lid will transform a casserole into a casserole à glacer.

Couvercle emboîtant: “Fitted cover,” meaning designed to slip down around the top of the pan like a cap. (Here the term takes the active –ant because it is encasing the pot beneath it.) These lids have a vertical flange running around the perimeter that fits closely to the body of the pan and creates a good seal to retain moisture during cooking. These are most commonly seen on box-shaped daubières and braisières, but when made for a round pan, the lid will transform a casserole into a casserole à glacer. Couvercles emboîtants sometimes have an indented area across the top or a raised vertical rim. I believe a slightly indented lid is designed to create an interior contour to direct condensation back down into the food so that it does not flow out under the lid’s edge. You’ll see this design on a range of stovetop braising pans. A raised vertical rim is a more antique design for the era of hearth cooking with braisières and daubières, when the lid with its rim became a platform to pile more hot coals on top of the pan.

Couvercles emboîtants sometimes have an indented area across the top or a raised vertical rim. I believe a slightly indented lid is designed to create an interior contour to direct condensation back down into the food so that it does not flow out under the lid’s edge. You’ll see this design on a range of stovetop braising pans. A raised vertical rim is a more antique design for the era of hearth cooking with braisières and daubières, when the lid with its rim became a platform to pile more hot coals on top of the pan.

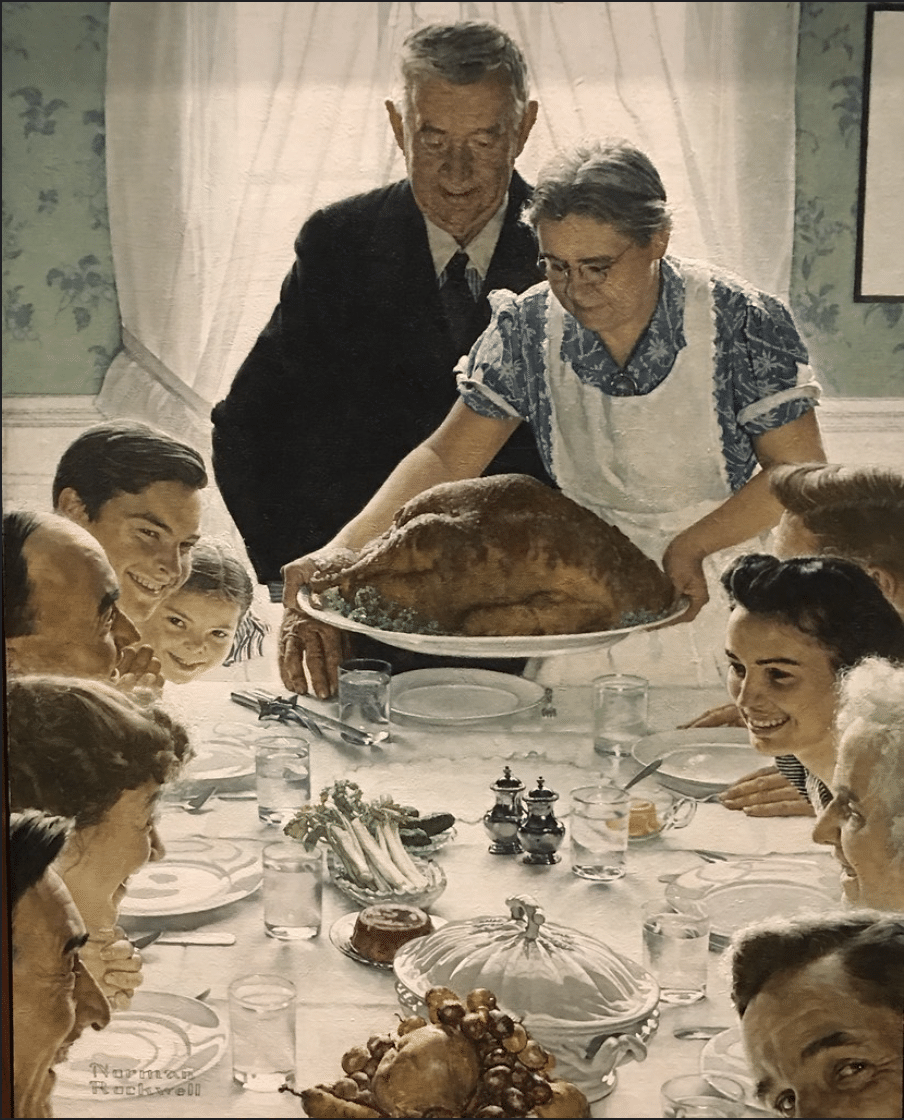

The culture of the United States in restaurants and homes is overwhelmingly à la russe, but we do have one service à la française that persists: the Thanksgiving turkey. Norman Rockwell’s 1942 painting “Freedom from Want” captures the iconic vision of the presentation of a cooked turkey, glorious and entire, to a table of smiling guests. This ritual, enshrined four centuries ago as the theatrical culmination of French haute cuisine, provokes the same reactions in everyone from kings to children: delight, gratitude, anticipation, fellowship, and best of all, un bon appétit.

The culture of the United States in restaurants and homes is overwhelmingly à la russe, but we do have one service à la française that persists: the Thanksgiving turkey. Norman Rockwell’s 1942 painting “Freedom from Want” captures the iconic vision of the presentation of a cooked turkey, glorious and entire, to a table of smiling guests. This ritual, enshrined four centuries ago as the theatrical culmination of French haute cuisine, provokes the same reactions in everyone from kings to children: delight, gratitude, anticipation, fellowship, and best of all, un bon appétit.