For me, this marque remains the most enigmatic of all the French makers.

History

I am deeply grateful to Jean-Philippe Jacquotot-Carisé for his generous contributions to this history.

The founder of chaudronnerie Jacquotot was Jean-Baptiste Jacquotot, born on Christmas Day in 1872. The first official record I can find for him is in 1908, when his workshop was located at 97 Rue de Grenelle.

Around 1914 he moved the chaudronnerie to 130 Rue de Grenelle and began a joint venture with “A. Dehillerin.” I’m not sure who this Dehillerin could be — of course it was a member of the de Hillerin family, but which one? Augustine de Hillerin, widow of founder Eugène, took over the running of the store after Eugène’s sudden death in 1902, but there was also her daughter Andrée. In any event, this association lasted until around 1921; in 1922, Jean-Baptiste expanded into 128 and 130 Rue de Grenelle and began to run the company under his own name.

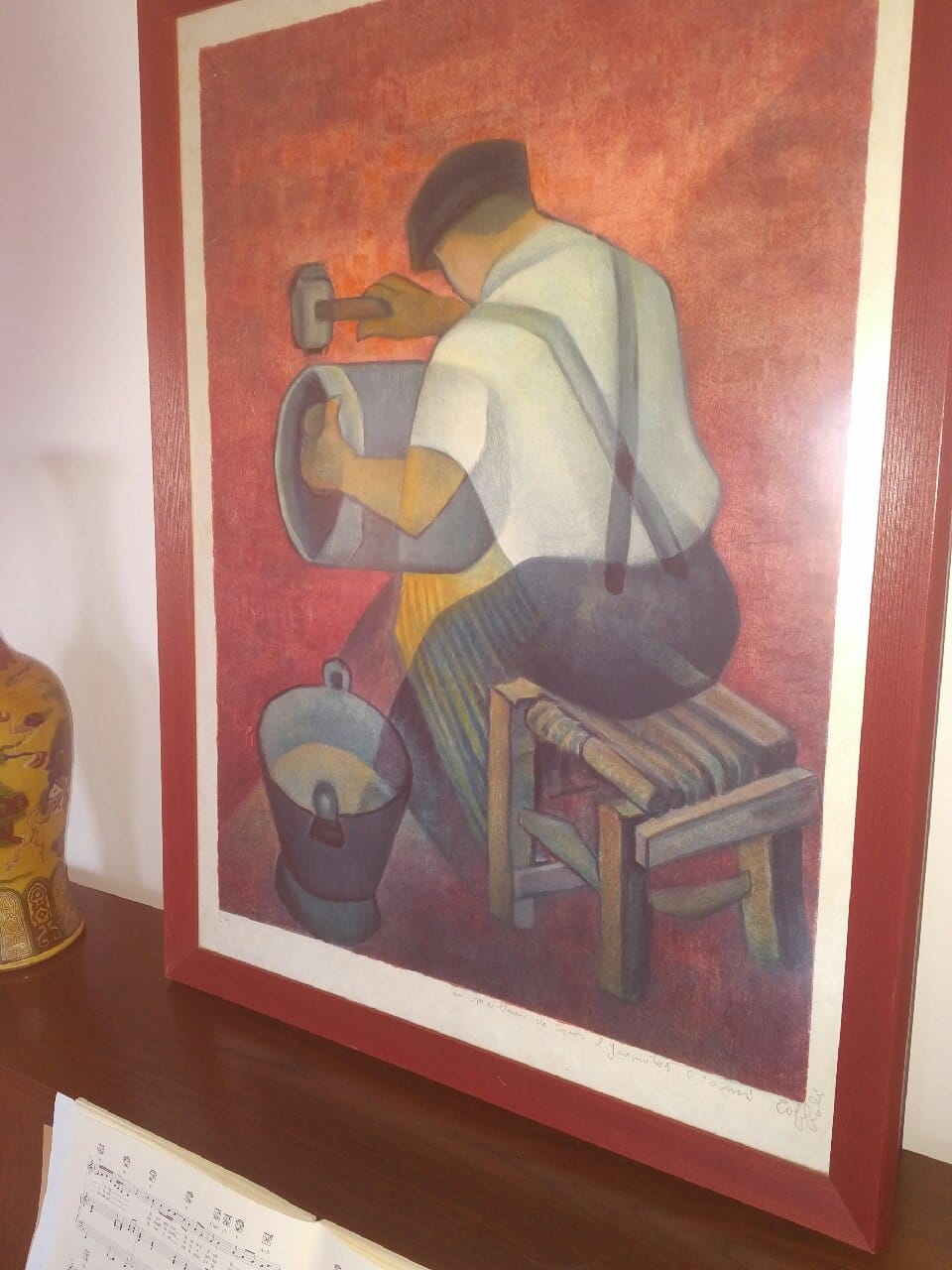

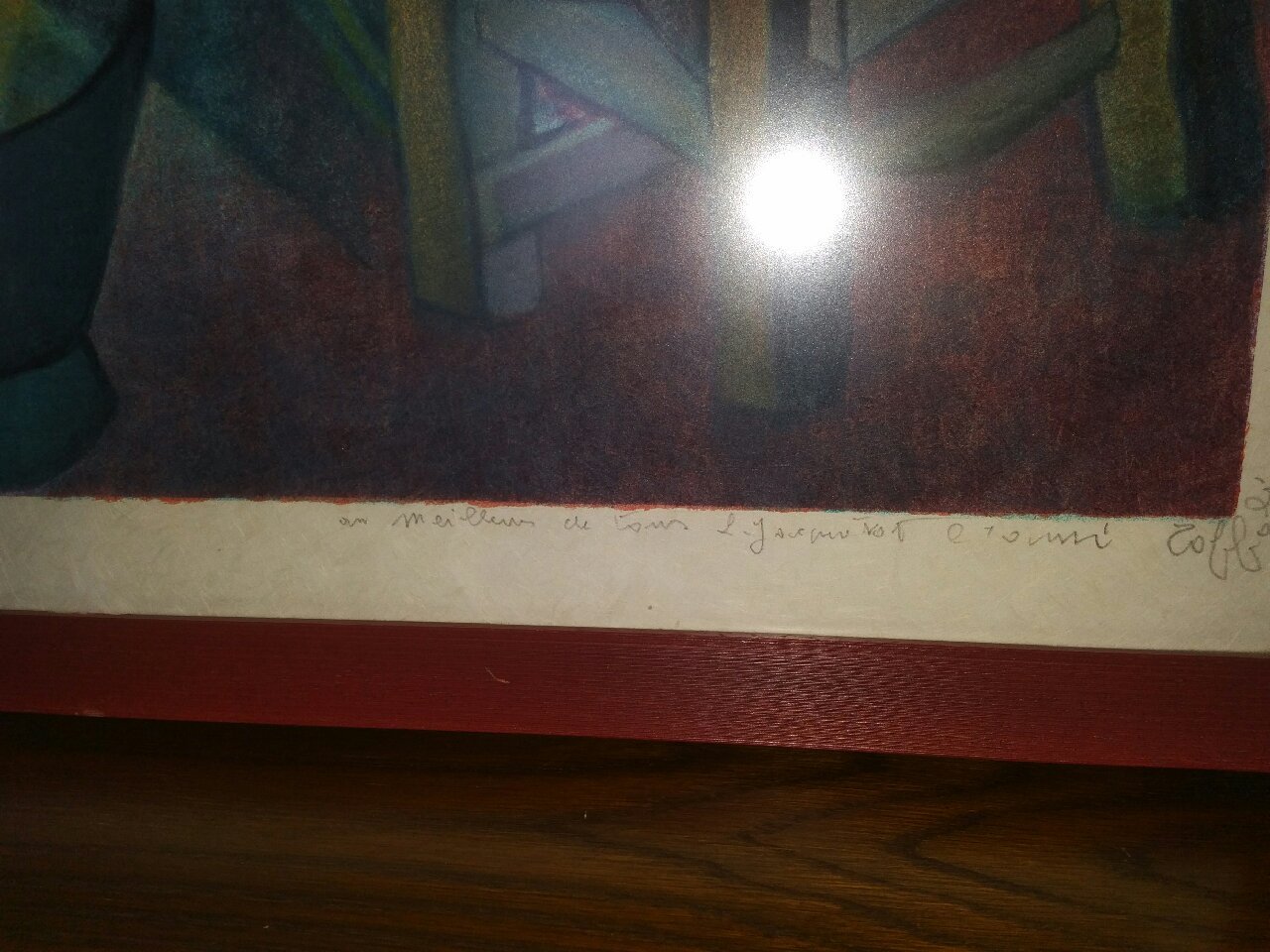

Below at left is an undated photo from the Jacquotot family collection that depicts young Jean-Baptiste, hammer in hand, at the start of his career. (This image is captured on a glass plate, a technology used into the late 1920s.) Below on the right is the frontispiece for a Jacquotot catalog during the Rue de Grenelle era.

Jean-Baptiste and his wife Pauline had a son, Alfred Louis, in 1903. Alfred enlisted in the army at the very end of World War I; after the war, he worked in Marseille for a few years as a dockhand before returning to Paris to join his father’s business. In the early 1920s he made the acquaintance of Germaine Léonie Ernestine Bouvier (1897-1990) whose family had a moving company with a warehouse at 77 Rue Damesme. Alfred and Germaine were married in 1928, and Jean-Baptiste negotiated the use of the Bouvier family’s large warehouse as a workshop for the growing business. Germaine had been a secretary since 1918 and after her marriage to Alfred, she joined Jacquotot and took on the administrative work. Alfred and Germaine’s daughter Janine Jaquotot (Jean-Philippe’s mother) was born in 1931.

Jean-Philippe shared the photos below of an original painting by the French painter Louis Toffoli (1907-1999) dedicated by the artist to Jean-Baptiste Jacquotot. Toffoli came to Paris in 1930 and it is not hard to imagine that his path crossed with Jean-Baptiste. The painting is entitled “Retinning and repairing a copper pot” and the dedication reads “One of the best of them all, J. Jacquotot, tinner.”

1939 brought war to France and forced change at Jacquotot as well. Jean-Baptiste and his wife Pauline retired and handed the company over to Alfred and Germaine. The family closed the store at 128 and 130 Rue de Grenelle in downtown Paris and moved the business to 77 Rue Damesme. Jacquotot was stretched thin, according to M. Jacquotot-Carisé, but managed to survive:

During the war, many young workers went to the front and were taken prisoner. The majority of those who stayed had to enter the service du travail obligatoire (STO, a compulsory labor service) in Germany. From then on, the few that remained were the “old ones” — hence the presence until the very beginning of the 1940s of Jean-Baptiste.

But the company, like many others, operated minimally to meet the needs of the restaurants that stayed open. Upon liberation, those who were able and wanted to resume their post were taken back. Then hiring took place with the resumption of all so-called “métiers de bouche” [professions in food preparation]. At the same time, hospitals and government departments — all of which had their own kitchens and kitchen staff — became customers.

The late 1940s until 1974 were glorious years for France and also for Jacquotot.

It was the recovery after the war and there was no lack of work. We were hiring — so much so that at Jacquotot there were two workshops at 77 rue Damesme: one for saucepans of all shapes and sizes, and a woodworking shop where we produced all the professional kitchen furniture as well as countertops for bars and restaurants (those called “zinc” could also be copper), fully equipped with built-in fridge. The premises were quite large, U-shaped with a paved courtyard in which the vans and two cars were held. (Don’t forget that it had been the Bouvier furniture mover who occupied these premises before Jacquotot.)

All of our clients resided in France and almost 90% in the Paris region; at the time there were very few large restaurants in the provinces. The customers included the more or less “grand” classic restaurants; the canteens and restaurants of hospitals and ministries; the private restaurant of the Elysée Palace [see photo at right], the Senate, and the Chamber of Deputies; and the “grands bourgeois” — individuals rich enough to have a chef at home in their Parisian domicile. Among these was an English prince who had married an American!

All of our clients resided in France and almost 90% in the Paris region; at the time there were very few large restaurants in the provinces. The customers included the more or less “grand” classic restaurants; the canteens and restaurants of hospitals and ministries; the private restaurant of the Elysée Palace [see photo at right], the Senate, and the Chamber of Deputies; and the “grands bourgeois” — individuals rich enough to have a chef at home in their Parisian domicile. Among these was an English prince who had married an American!

The photo below captures four generations of his family gathered at the family’s house in Saint-Mandé east of Paris to celebrate Jean-Philippe’s birth. In the front row are great-grandfather Jean-Baptiste Jacquotot and great-grandmother Pauline Jacquotot, both looking into the camera, and in profile is great-grandmother Léonie Bouvier. (Says Jean-Philippe, “Pauline has a somewhat severe expression in this photo, but in reality she was a lovely great-grandmother who taught me many things.”) In the back row is mother Janine Jacquotot and grandmother Germaine Bouvier Jacquotot, who cradles Jean-Philippe as any doting grandmother would do. The only one missing from the photo is Alfred Jacquotot, who took the photo.

Jean-Baptiste passed away in 1955, followed by his wife Pauline a decade later in 1966; under the leadership of Alfred and Germaine, the company flourished as the French economy recovered and prospered. But the company did not pursue the burgeoning post-war export market in the United States, unlike Mauviel and other makers.

We practically did not export at all: our customers bought in France and left with their equipment. For us they were individuals, and the quantities did not suggest resale in the USA. In fact, it was the chefs who came to us, coming to 77 rue Damesme with a clerk and, if necessary, the equivalent of the financial manager (if down payments were necessary). Then, depending on the deadlines, it was Jacquotot who delivered products to them.

As far as maintenance was concerned, the scheme was almost identical: the chef would call, and we would send a van with two workers who collected the equipment to be repaired and brought it back to 77 rue Damesme. Depending on the stock at the customer (the majority of kitchens rotated two or three sets of pans), during this trip to pick up items needing work we also brought a replacement set so that the kitchen could continue without interruption.

Simple and efficient for the customer.

Jean-Philippe marks the end of this era of growth with the year 1974, when world events and France’s own economic policy brought post-war expansionism to an end.

Mentalities began to change and evolve, modernism and the economy became key words even for restaurants and canteens. We were able to continue with sales and maintenance, but very quickly the joinery workshops closed, and Jacquotot like the two others limited themselves to all kitchen equipment.

In addition, competition had arisen with small craftsmen in the provinces doing tinning at very low prices (not having the same costs, among other things) but with lower quality, which seemed to be sufficient for some customers.

The 1990s was a period of change for Jacquotot. According to Jean-Philippe, the company was forced out of the 77 Rue Damesme workshop due to concerns about the industrial chemicals involved in metalworking; indeed, Parisian cadastral records show that “two one-story buildings for residential and industrial premises, vacant and unoccupied” at 77 Rue Damesme were demolished in October 1990. The family relocated from Paris to Plaisir just west of Versailles. The company no longer manufactured copper but turned to retinning and refurbishing it. Alfred passed away in 1991 and his daughter Janine took over the firm. The company’s specialty was producing an exceptional mirror polish as shown in the photo below.

According to the family, the company finally closed its doors in 2000.

According to the family, the company finally closed its doors in 2000.

The Jacquotot family is buried at the Cimitère Sud de Saint-Mandé: Jean-Baptiste (1872-1955), Pauline (1873-1966), Alfred (1903-1991), and Germaine (1897-1990). Jean-Phillippe and his children remember them fondly.

Jacquotot stamps

There are four five six seven eight nine versions of Jacquotot stamp and I offer these tentative date ranges based on information I’ve been able to confirm online. (My thanks as always to readers who reach out to me with examples that they do not see represented here — I am indebted to you for filling in the blank spots! Thank you!)

97 Rue de Grenelle: 1907 to possibly 1913 |

|

| The very earliest record I have for Jacquotot in business at 97 Rue de Grenelle is the 1908 Paris almanac — implying that the business was established most likely in 1907.

This circular stamp is unusual. The convention at the time was for oval stamps — see the several examples to follow — so this may have been an experiment or a limited run or something like that. Thanks to Val Maguire for the photo. |

|

| A reader was kind enough to provide this stamp, also from 97 Rue de Grenelle. This is the familiar oval style that’s similar to Dehillerin, Gaillard, and the other Parisian makers.

Jacquotot stayed at this address until at least 1911. The next online record after that is dated 1914, at which time he had relocated to number 130. So my best guess is that this stamp was in use from 1907 to as late as 1913. |

|

130 Rue de Grenelle: 1914 to 1921 |

|

| I believe Jean-Baptiste Jacquotot moved his chaudronnerie from 97 Rue de Grenelle to 130 Rue de Grenelle sometime around 1913. He formed a joint venture with “A. Dehillerin” that lasted until about 1920 and this stamp represents copper under that arrangement.

Stylistically, this stamp reminds me most strongly of the early Mauviel-Gauthier Frères stamp that also has the same long name curving overtop the address and city. |

|

| This stamp is so stylistically similar to the 97 Rue de Grenelle stamp that preceded it and the 128 & 130 stamp to follow that I suspect it represents Jacquotot production.

For the purposes of estimating age, this stamp could be from 1913 or so until 1922, a little longer than the Jacquotot-Dehillerin work, as far as I can tell. |

|

| This very rare Jacquotot stamp with the 130 Rue de Grenelle address is the only example of its kind that I’ve seen. Note the plain typeface and the italicized Paris: it is stylistically quite distinct from other Jacquotot marks, to the point where I suspect it might be production from a second workshop that supplied Jacquotot’s growing kitchenware supply business.

The 130 Rue de Grenelle address still points to that 1914 to 1921 time period. I don’t have enough information at this point to identify the maker. (Stamp example courtesy of Stephen W.) |

|

128 & 130 Rue de Grenelle: 1922 to 1940s? |

|

| In 1922, the company expanded to 128 & 130 Rue de Grenelle. Business records show Jacquotot operating at this address through 1938 but the records themselves disappear after that.

I think this is a stamp from the early end of that timeframe. It looks very similar to the 130 Rue de Grenelle version just above; the addition of “& 128” required abbreviating “Rue” to “R.” Note also the “Grenelle” is now in small capitals. |

|

| I believe this linear version of the stamp is from the later end of the time period at Rue de Grenelle. Unfortunately I don’t know the date at which they changed from one stamp to another.

I know Jacquotot was at this address as of 1938, but there are no records during the war, so I don’t know exactly how long they stayed until their next move. (Photo courtesy Matt.) |

|

77 Rue Damesme: 1950s to 1990s? |

|

| Sometime between 1938 and the 1960s, Jacquotot moved from Rue de Grenelle to 77 Rue Damesme. The stamp, a simple three lines of text, is stylistically identical to the one just above.

77 Rue Damesme served as the Jacquotot workshop since the marriage of Alfred and Germaine in 1928, while 128 & 130 Rue de Grenelle was the storefront in the busy downtown 7th. |

|

J. Jacquotot, Made in France: 1960s to 1990s? |

|

| This stamp is a recent discovery. It is simply “J. JACQUOTOT” with no address and a MADE IN FRANCE stamp.

There is a lot to unpack here. Right away, this is a 1960s and later pan, because it has the Made in France stamp. But take a good look at that Made in France — it looks just like the “two-line oval” version on my Made in France page. In my experience, that is a Mauviel mark! (Deep thanks to reader Arndt for catching this and drawing my attention to it!) Update: Jean-Philippe has confirmed that Mauviel produced some pieces for Jacquotot. |

|

Bonjour j ai dit que ma mère Janine jacquotot qui avait repris l’entreprise est décédée à pâques 2000. Germaine était ma grand-mère et l épouse d Alfred et la mère de janine bien cordialement. J Ph carisé jacquotot

Merci M. Carisé-Jacquotot pour la correction! C’est une erreur de traduction de ma part qui m’a amené à mal vous comprendre. Merci!

Hello M. Carise-Jacquotot, if you have read through the posts on this site

you will have seen there are questions concerning the history of Jacquotot. At some point in time, towards the end of their production, Jacquotot procured pans from Mauviel to sell them from their own store and stamped them with the Jacquotot name. Are you able to let us know what year this re-branding started? Thank you for any information you might provide.

Bonjour

j’ai en mémoire le nom de Mauviel comme fournisseur, à partir de fin des années 60 débuts années 70; néanmoins pour certains clients il leur était fabriqué des casseroles “sur mesure” à partir de plaque de cuivre qui étaient formées et martelées (aspect extérieur) à la main par certains ouvriers, puis suivant les formes on ajoutait le fond toujours en cuivre et les queues fonte (en fonte) rivetées, puis on étamait l’intérieur.- là encore à la main avec des bourres spéciales qui permettaient un étalement uni sans coulure, de l’étain chaud.

pour information: casserole étamée = casserole avec de l’étain à l’intérieur. et c’était de l’étain spécial, dit “alimentaire”.

Thank you for your reply sir. I greatly admire the pans that came from the Jacquotot shop.

I recently acquired a 22cm saucepan with the later linear 128&130 R. De Grenelle stamp, whose construction may shed a little light on the time period of that stamp.

https://imgur.com/a/9aqJtyF

It was puzzling at first why a pan with a stamp that dates it toward the middle of the 20th century would have a construction that suggests late 19th century, when so much changed in those 50 or so years.

Its proportions are also a little odd, much taller than was common for saucepans of the time at 14cm

My first though was that it looked like a late 19th century soup pot with the top third cut off and a cast iron handle added. That is of course a possibility.

But then upon considering how M. Jacquotot-Carisé highlighted the difficulty faced by the company during the war as the majority of the workforce was either called to serve or pressed in to compulsory work toward the war effort an alternative theory emerged. As he puts it, « the few that remained were the “old ones” ».

It is conceivable that this pot was actually made after the outbreak of the war, by one of those “old ones”, who had learned to make pots as an apprentice, in exactly this way, without the assistance of a stamp or a press.

It also occurred to me that not only the workforce, but also the machinery might have been sequestered, essential as it would be in the manufacture of artillery munitions.

The poor finishing of the iron handle also suggests a bare minimum approach to manufacture that would be likely during a time of war.

While there are other possible explanations, I’m leaning towards this being an example of a pot made at a time when circumstance had forced the chaudronnerie to operate as they had some 50 years previous, with an aged but experienced, skeleton staff of old timers, ticking over to keep producing the basic cookware the capital would continue to need.

That being the case, while there is no record of Jacquotot maintaining their presence at 128 & 130 Rue de Grenelle after 1938, I think that this pan suggests that it continued at least through the war.

Alex, you have some very interesting thoughts about making an unusual and very beautiful pot. Wartime depletion and the consequent contingency measures and improvisations are compelling arguments for traditional manufacturing. I was always amazed when I came across pieces whose hallmarks indicated production around the middle of the last century, but which still showed some classic signs of artisanal production. In particular, I remember distinct bevels I saw on Gaillard (1940-60) pans and a Paul Manzoni (Switzerland) saucepan. The latter bears the date stamp 1941. In addition to the need to rely on older workers in wartime, it should also be remembered that small artisan workshops such as Paul Manzoni’s did not have the machinery of larger ones. The Manzonis were six brothers, each of whom had their own small workshop in different places in the canton of Graubünden. Anyone who completed a four-year apprenticeship as a coppersmith in Switzerland will certainly have used this skill in traditional production for a long time to come.

Hi Alex, I believe it is also possible that an old pan was refurbished by Jacquotot who then added their current stamp to it. In the late 30’s and early 40’s the workers had access to contemporary machinery so I doubt if they would have reverted to the old dovetail construction.