Here’s some guidance on the type of lid you have — or what type you need.

- Part 1: Flat and fitted lids

- Fitted versus flat style

- Stick handle versus top handle

- Matching a flat or fitted lid to a pan

- Handle metal

- Handle type

- Country of origin

- French

- Belgian

- English

- Era

- Tips to size a flat or fitted lid

- Part 2: Cap lids

- Matching a cap lid to a pan

- Tips to size a cap lid

Part 1: Flat and fitted lids

The most common types of lids made by the French (and European) coppersmiths are shown below.

Fitted versus flat style

A “fitted” lid (couvercle à degré) has an indented area, while a “flat” lid (couvercle plât) is perfectly flat from edge to edge.

- A fitted lid provides a good seal over the pot. The indented area guides the lid to settle neatly over the rim and stay in place. One benefit of this design is that condensation forming on the underside of the lid tends to drip back down into the food, maintaining moisture. The downside, of course, is that a fitted lid will only function as intended when covering a pan of the corresponding size.

- A flat lid provides a relatively loose seal. This lid rests on top of the rim of the pan and any variation in the contour of the lid or the elevation of the rim will produce a gap. (A perfectly new pan and a perfectly new flat lid may seal together quite well, but in my experience, very few pans and lids are perfect.) The big upside of a flat lid is that it can be used on a wide range of pans — hence its other name, a “universal lid.” But the downside is that the imperfect seal does not prevent evaporation; condensation forming on the underside can roll to the edge of the lid’s rim and drop onto the cooktop, not back into the food. In some ways a flat lid is more of a splash guard than a sealing lid.

Stick handle versus top handle

A “stick handle” (queue) projects out to the side, while a “top handle” (poignée) is a bracket positioned at the center of the lid.

Matching a flat or fitted lid to a pan

Let’s say you have an antique copper pot with a missing lid — or, just as likely, a lovely lid that is looking for a pot — and you’d like to follow the French aesthetic to find its mate. I have some suggestions for you based on what I’ve observed.

Handle metal

The metal of the handles on the pot and its lid should match. If your pot has brass handles, the lid should have a brass handle as well; if your pot has an iron handle, the lid’s handle should be of the same type of iron. (All about iron handles has more information about the three types of iron used in French copper cookware.)

Forged iron handle |

Wrought iron handle |

Cast iron handle |

Handle type

In general, a pot or pan with a projecting stick handle — such as a saucepan or sauté pan — was expected to have a lid with a stick handle as well. (I suspect this was so that pot and lid handles could be clamped together to be carried around the kitchen.) Accordingly, a pan with side bracket handles — a stockpot, stewpot, or rondeau — would also have a lid with a bracket handle.

Country of origin

French, Belgian, and English coppersmiths developed distinct aesthetics for the design of their handles, and this extends to the lids as well. Here are some examples of lid handles to help you identify the style most appropriate to a particular pot.

French style

|

|

|

|

|

|

A sub-type of French style are the custom handle designs for the three great Paris department stores À La Ménagère, Allez Frères, and Grands Magasins du Louvre. The lid handles resemble the shape of the handles on the pans; the shape of iron and brass handles are the same.

À La Ménagère |

Allez Frères |

Grands Magasins du Louvre |

Belgian style

|

|

English style

|

|

Era

Lids are not complicated objects. While evolutions in coppersmithing are clearly reflected in pots and pans — dovetails to welding, hand-rolled rivets to machine-made, hand-hammered to machine-shaped — lids have stayed pretty much the same. That said, there are a few things you can do to find an age-appropriate lid and pot.

For iron handles, match the type of iron. There was an evolution from forged iron handles (18th to early 19th century) to wrought iron handles (early to mid 19th century) to cast iron handles (late 19th century to the present day). An iron-handled pot and lid made at the same time would have had the same type of iron, so learn how to distinguish them and try to match lids and pots.

For a French lid with brass bracket handles, count the rivets. My observation is that antique — that is, pre-WWII — brass lid handles were attached with two rivets per bracket. French pieces I have dated with reasonable certainty to the post-WWII era (and up to the present day) have just one rivet per bracket. In fact, this is a visual shortcut I use to date a pot and lid: if the brackets have two rivets apiece, it’s likely pre-WWII.

In the examples below, the top row are antique-era (pre-WWII) lids with double rivets, while the bottom row are recent-era lids with single rivets.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tips to size a flat or fitted lid

Use diameter correctly. The convention in vintage French copper cookware is that pots and pans are described by the inside diameter, not from outer edge to outer edge. A “24cm saucepan” measures 24cm across the interior, while the outside dimension may be larger. Accordingly, a fitted “24cm lid” is sized to fit a pot with an interior diameter of 24cm, taking into account the inset dimensions as discussed above; by contrast, a flat “universal” lid that is 24cm diameter edge to edge will be a little small for a 24cm saucepan! If you are fortunate enough to have an antique piece with a size stamp, pay attention to it — it’s there to take the guesswork out of what pot or lid will fit.

Use diameter correctly. The convention in vintage French copper cookware is that pots and pans are described by the inside diameter, not from outer edge to outer edge. A “24cm saucepan” measures 24cm across the interior, while the outside dimension may be larger. Accordingly, a fitted “24cm lid” is sized to fit a pot with an interior diameter of 24cm, taking into account the inset dimensions as discussed above; by contrast, a flat “universal” lid that is 24cm diameter edge to edge will be a little small for a 24cm saucepan! If you are fortunate enough to have an antique piece with a size stamp, pay attention to it — it’s there to take the guesswork out of what pot or lid will fit.

And as a corollary, always take a close look at the measurements provided in an online listing and factor in the possibility that the seller isn’t referring to inside dimensions. Sellers may not be aware of the importance of using internal diameter. A fitted lid “measuring just over 7 inches across” could be 18cm (7.1 inches) across its external diameter, but is most likely sized with the correct inset and overhang for a 16cm pot with an internal diameter of 6.3 inches. Along the same vein, a pot “measuring 39.2cm in diameter” is likely a 38cm and would need a lid of the correct size.

Flat “universal” lids are straightforward: As long as the lid is a little bigger than the pot, it’ll work just fine. If your flat lid has a size stamp, it should fit a pot of the same inner diameter (and anything smaller) with enough overhang to be stable. But if the lid is unstamped, measure it edge to edge and subtract a centimeter or two to derive its maximum pot coverage size.

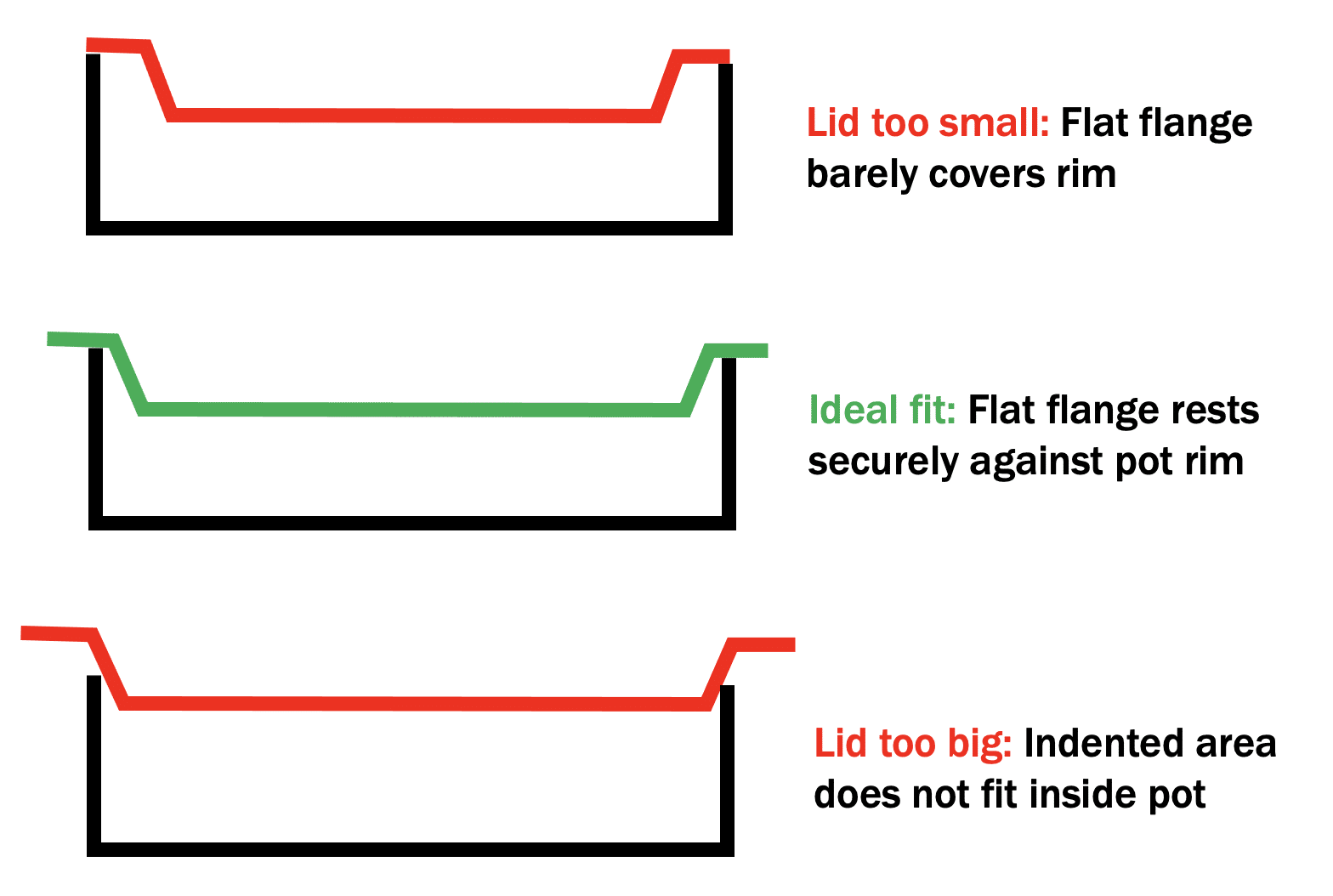

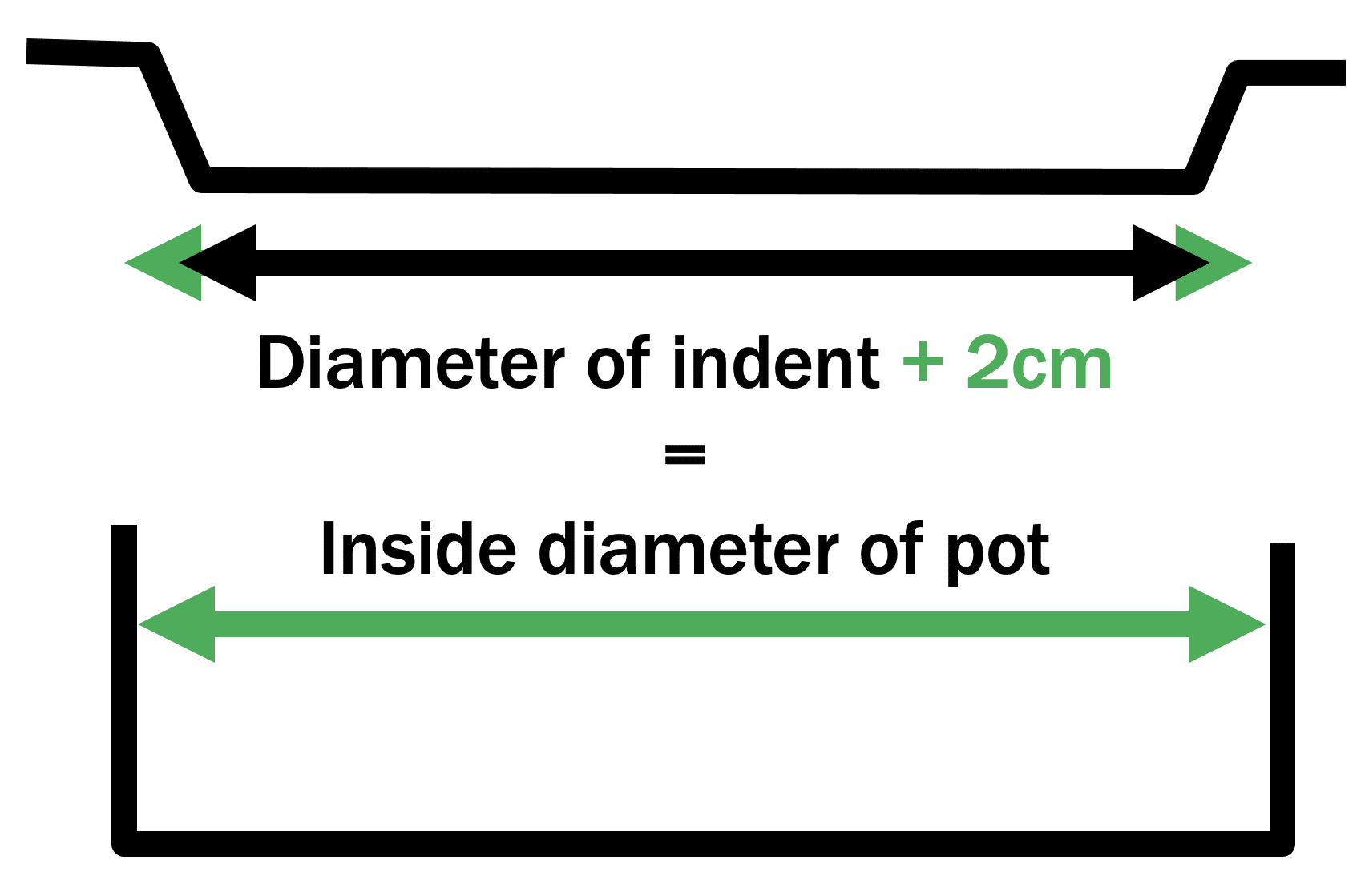

Fitted lids require measuring. Unless your pot and lid have size markings on them, you’ll need to measure them to be sure they’ll fit. In order to ensure that the lid will drop down within the pot, the diameter of the indentation must be slightly smaller than the interior diameter of the pot. Here’s a quick visual guide, using some of my handy-dandy Not Quite Professional Quality™ graphics.

If you are buying a lid for a pot or finding a pot to fit a lid you have, I suggest you follow this guideline: The diameter of the indented area of the lid plus 2 centimeters should equal the inside diameter of the pot. For smaller pots (under 20cm or so), the difference in size should be a little less; for larger pots (above 36cm or so), the difference should be a little more.

Be prepared for wonky geometry. The larger and older a pot, the more likely that it has taken some blows or has been dropped or whatever and is “out of round” — that is, no longer perfectly circular. In the top-down photo at right of my beloved 34cm Dehillerin rondeau, the black outline indicates a true circle and you can see how the shape of the pot deviates.

Be prepared for wonky geometry. The larger and older a pot, the more likely that it has taken some blows or has been dropped or whatever and is “out of round” — that is, no longer perfectly circular. In the top-down photo at right of my beloved 34cm Dehillerin rondeau, the black outline indicates a true circle and you can see how the shape of the pot deviates.

A 34cm fitted lid is never going to settle properly on this rondeau. I use a flat universal lid wit this pan when I need to cover it. This problem is most acute with short-sided pots (such as a rondeau or stewpot); I can sometimes get away with cramming a lid onto a wonky stockpot because the taller sidewalls can flex a bit back into shape. But the best fix of all would be to send the piece to a professional retinner to see if it can be restored to the correct geometry.

Part 2: Cap lids

There is a style of lid that slides down over the top of the pot like a cap and features stick or bracket handles mounted on the top or the side. The French term for this style of lid is couvercle emboîtant or couvercle à emboîtage; the French term boîte means “box,” and this style of lid is intended to seal up the pot so that moisture stays contained. These lids are for slow-cooking: braising, simmering stock, and other tasks where the goal is to retain all the liquid in the dish.

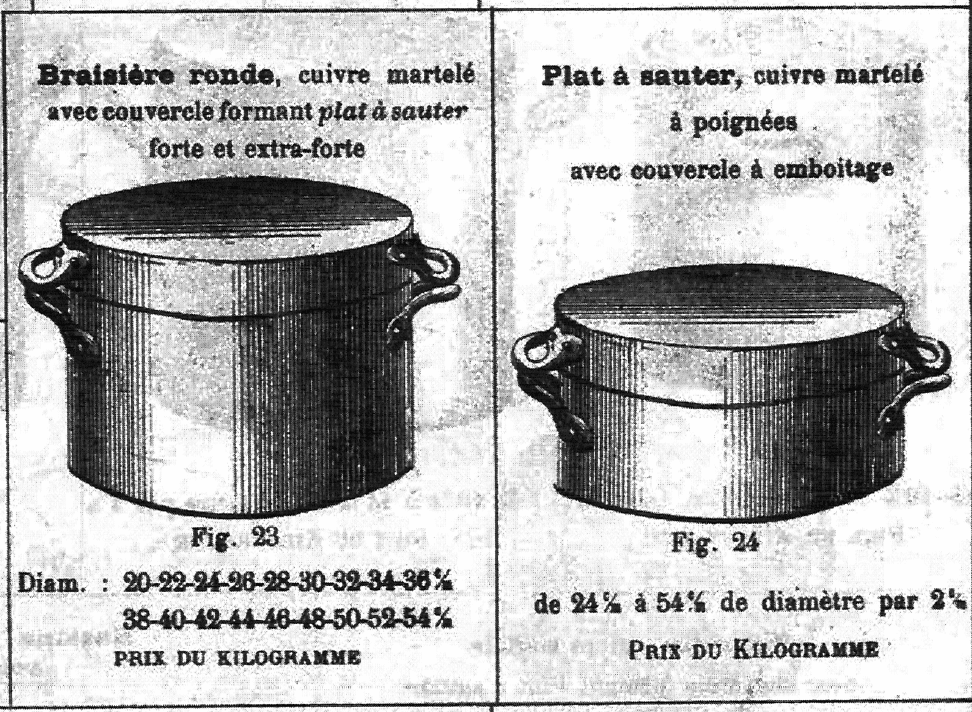

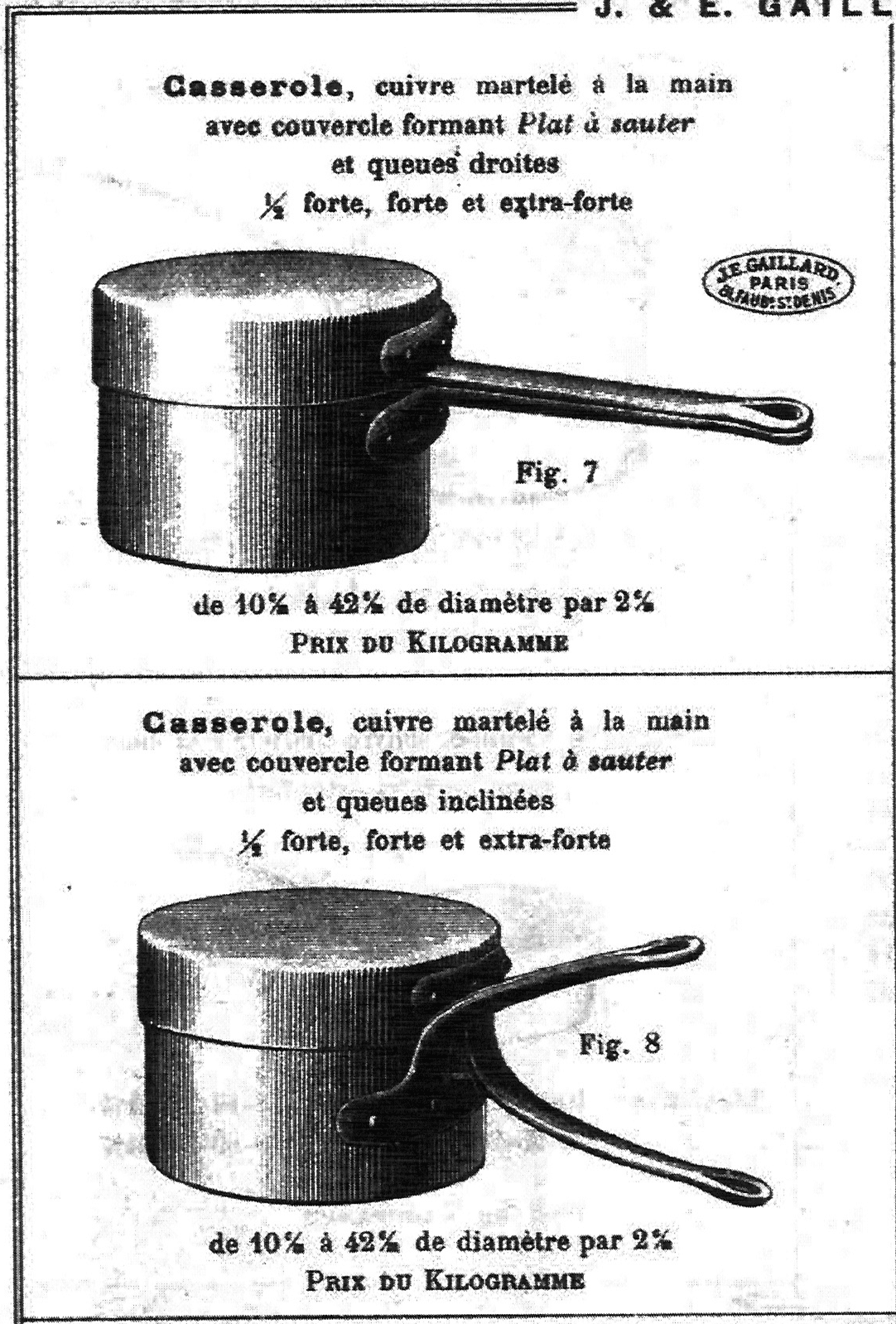

I am most accustomed to seeing this style of lid on daubières and braisières, those iconic box-shaped braising vessels, but the French chaudronniers offered couvercles emboîtants for a range of pieces. A cap-style lid with side-mounted handles has a second use: flip it over and it becomes a shallow sauté. This benefit is explicitly called out in the old catalogs: listings for pieces with side-handled cap-style lids often included the notation couvercle formant plat à sauter — “cover forming a sauté platter.” Below are some examples from Gaillard’s 1914 catalog.

|

|

|

|

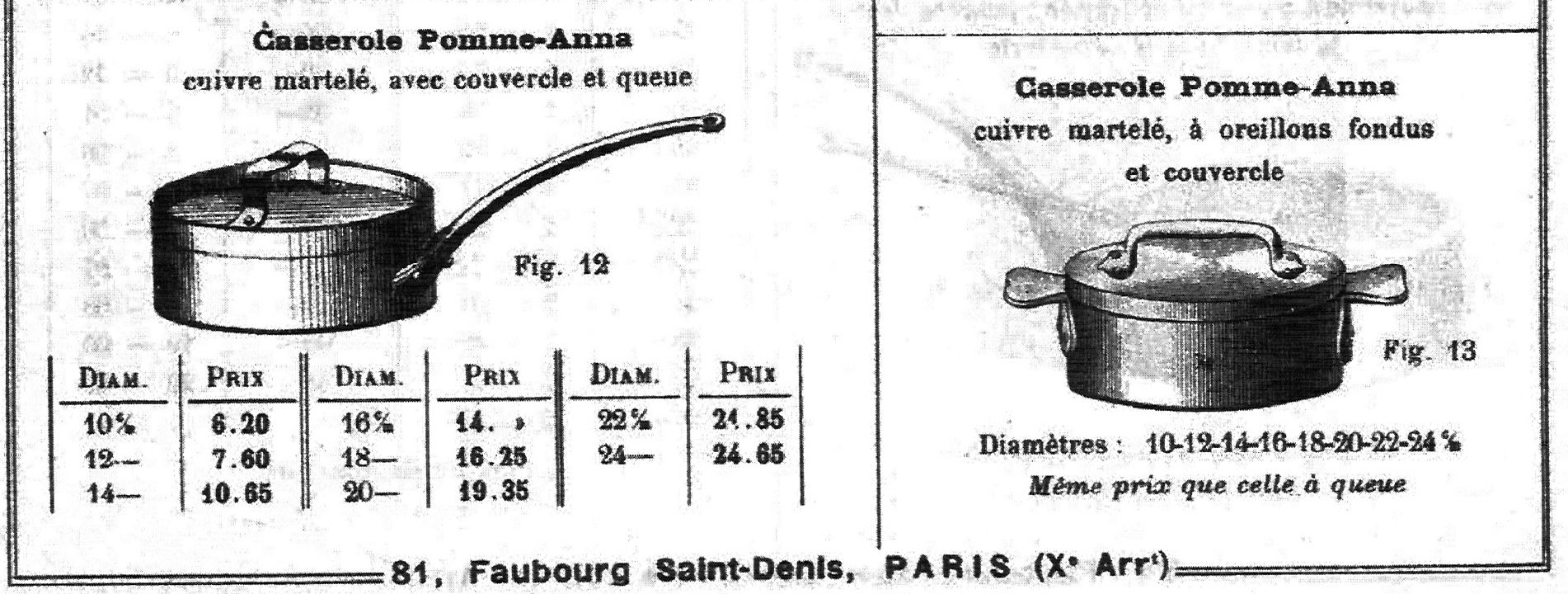

You may also see a cap-style lid on older pommes Anna pans. The modern version features petite side mounted oreillons (“ears”) for handles with a flat lid, but note that Gaillard in 1914 offered both stick-handled and oreillon versions with top-handled cap lids.

Matching a cap lid to a pan

The first consideration should be to select the right type of pan. As above, the French makers offered cap lids on a range of pots and pans but they all had one thing in common: straight sidewalls. I do not believe a cap lid would work on curved pans (skillets, gratins, and sauteuses bombées for example) or flared pans (sauteuses évasées aka windsors). I also do not see cap lids fitted on poaching pans such as poissonnières or turbotières or on roasting pans. Stick to pieces with vertical walls and you should be okay.

Beyond that, the advice I offer above for flat and fitted lids applies here as well: match the handle configuration, metal type, country of origin, and era of pot and pan and you should be in good shape.

But if you want to take it to the next level, or if you’re a collector trying to restore a piece to its original condition, you can try to establish whether your specific piece (or the one you’re eyeing to buy) originally had a cap lid or not.

In my experience, cap lids fit so closely that they often left marks on the pot’s copper. Oftentimes if you look carefully an inch or so below the top rim, you can see vertical scrapes or a ring around the rim where the edge of the cap lid clamped most tightly. But if you are evaluating a pot in an effort to determine whether it had a cap lid or not, you will need to apply some judgement.

The tricky thing is that an English tinning job that has been removed will leave similar traces. The English style of tinning pots was to leave a band of tin around the outside of the rim. John Fuller Sr. writes in the Art of Coppersmithing (1893), recollecting English practices in the mid-19th century, that the tinning band was “marked off” when the pot was made, and I believe this was done by laying down a light score mark about an inch or so below the rim. You can see this on my English stockpot below, which has its tin band preserved. The score mark is clearly visible in the closeup photo on the right. The cap lid did not leave this mark: when it is in place, the lid extends another quarter inch or so below the score mark, as evidenced by the darkened region extending below the line.

English stockpot with intact tin band |

Closeup of score mark |

If the restoration of an English pot removes instead of refreshes this tin band, the score mark may be revealed, and it can look an awful lot like the chafing mark left by a tight cap lid. Below on the left is an English Benham & Froud saucepan (not one of mine) with a horizontal line below the rim that I believe is the tinning score mark. On the right is the rim of a French stockpot from my collection that retains its original well-fitting cap lid, and you can see that the pot has picked up a depression around the rim corresponding to the edge of the cap lid. But to my eye the ring around the French pot looks quite similar to the score mark on the English piece.

English Benham & Froud saucepan with tin band removed |

French stockpot (1880s-1900s) with original cap-style lid |

Could I be mistaken, and the Benham saucepan above was originally fitted with a cap lid that left those marks? Of course I cannot be 100% certain, but based on what I have observed in a few years of studying copper, the English style was to put cap lids on stockpots and stewpots but not on saucepans or sauté pans.

I have a final example to illustrate the challenges here. I have a 26cm Gaillard (1890-1900s) stockpot that came to me without a lid, and I am reasonably sure — but not 100% positive — that it originally had a cap lid. The evidence is this line running around the entire rim, about two centimeters from the top.

I think that line is a mark left from the edge of a cap lid because I can see “twist off” scratches as though the lid was so tight that it needed to be spun off the top of the pot. My misgiving is that two centimeters is not a lot of depth for a cap lid, but hat said, it’s also not a lot of depth for an English tinning job which would be the other possibility.

At the moment I’m keeping an eye out for an appropriate cap lid. As a collector, my ideal lid would be a cap lid with French-style side handles made by Gaillard in the 1920s to 1930s, but I’m not holding my breath on this one. I’d be lucky just to find a lid that fits this pot. Which leads to the next section…

Tips to size a cap lid

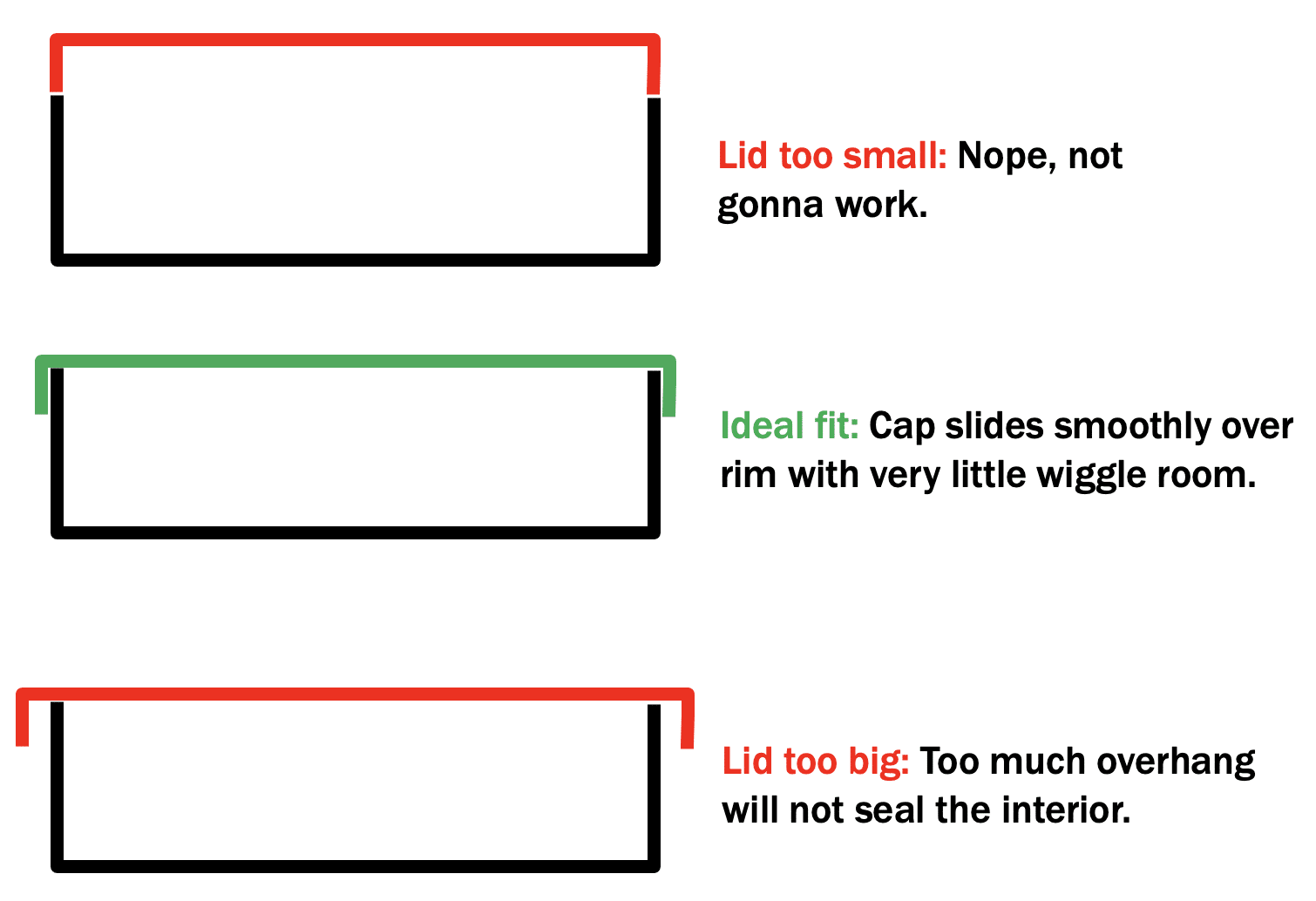

Sizing a cap lid presents a precise measurement challenge: it has to be just big enough to fit but not so big that it fits loosely. If the lid and pot are too close in size, the lid will not slide over the top of the pot or will jam so tightly that it will distort; a cap lid that is too large for the pot will sit atop the rim but will not form a seal.

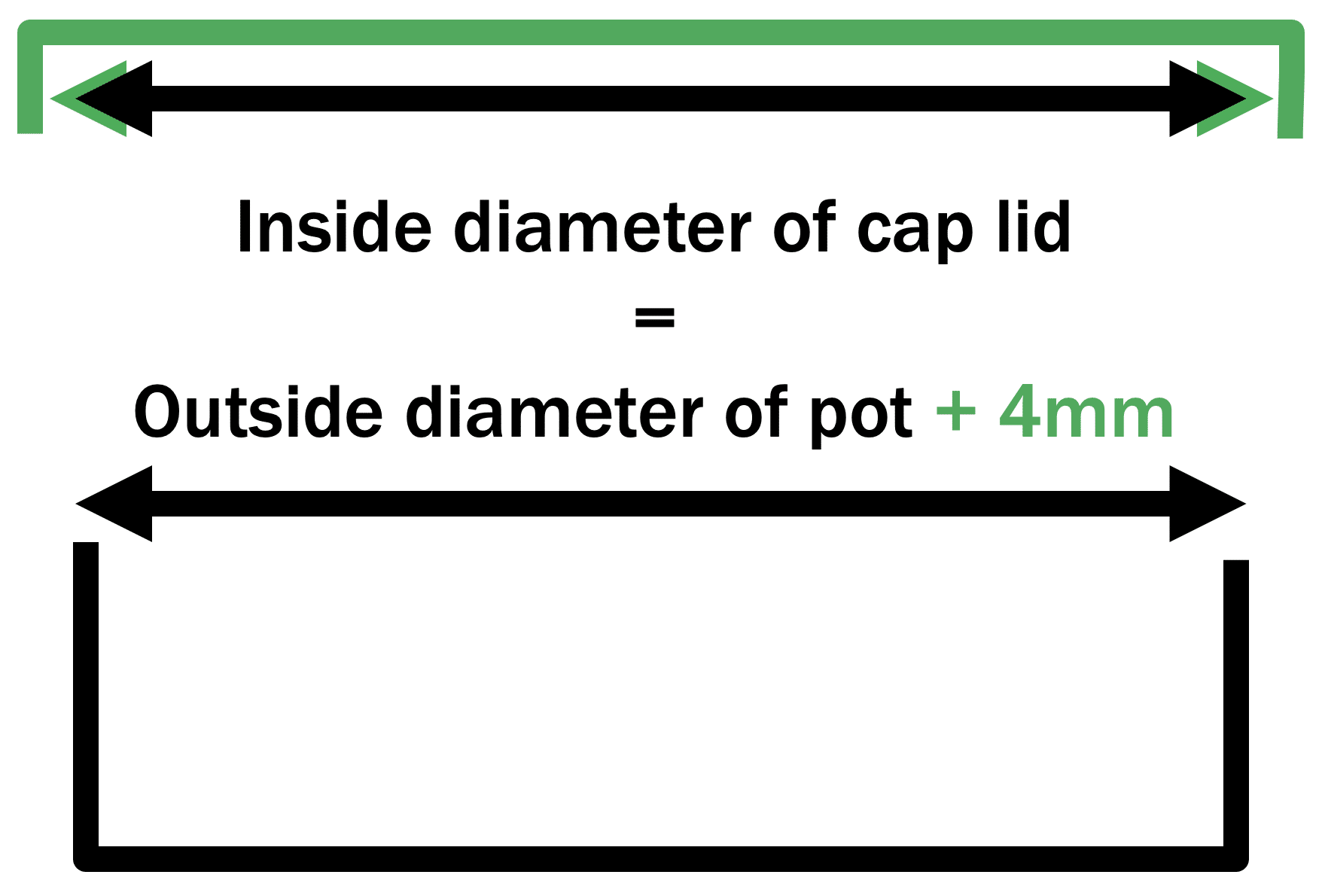

Because a cap lid embraces the outside of a pot, you need to measure the exterior diameter of the pot and find a cap lid with an interior diameter just a little larger. As a guideline, I suggest the interior diameter of the lid should be 4mm or so larger than the outside of the pot, but you could go a millimeter or too more loose if needed.

I hope this guidance helps you! As always, feel free to reach out by email or via the Contact Me page.