A piece of Lecellier copper is the work of a family with centuries of history in Villedieu.

Copper with a Lecellier stamp turns up frequently on eBay and Etsy and I believe the majority can be traced back to Lucien Lecellier and his eponymous 20th-century chaudronnerie. He took the reins of the family company from his father in the 1930s, survived World War II, and rode the wave of US and international interest in French copper in the 1960s. During the 1970s to 1990s, L. Lecellier produced copper cookware with tin, aluminum, nickel, and steel lining, as well as cuivre d’art — decorative platters, vases, ewers, and more — before closing its doors around 1993.

There is very little written about Lucien, but what I have discovered of him reminds me of Armand Mauviel, who also guided his own family’s firm from the disarray of World War II to an international brand. Though Lecellier does not survive today, I suggest you consider it equivalent to Mauviel, as it is just as beautiful and innovative for its time and can make similar claims to history and tradition.

Lecellier from the 19th to the 20th century

Villedieu-les-Poêles has been a center of metalworking since the 12th century and I would not be surprised if the Lecellier family was there from the start. I’ve been poking through some family trees online and the earliest documented Lecellier in the Villedieu area I can find on Geneanet.org is Vincent Lecellier, born around 1557. But the absence of evidence of Lecelliers in French baptismal and funerary records — robust as they are — should not be construed as evidence of absence of Lecelliers in Villedieu.

The Lecelliers married and crafted copper with Mauviels, Havards, Huards, Le Maitres, and Tétrels. By 1857, there were 67 poêleries-chaudronneries listed in Villedieu, and of these, five were run by Lecelliers, representing marriages, inheritances, and commercial alliances to feed the growing appetite for copper cookware in Paris and the cosmopolitan capitals of Europe. My research on Geneanet.org has lead me to identify Joseph Philémon Lecellier (1802-1885) as the patriarch poêlier-chaudronnier of the Lecelliers during this time. Of his eight children, three sons went on to form their own chaudronneries to carry the Lecellier name into the 20th century.

- Eldest son Pierre Émile Lecellier (1829-1866) and his wife Anna Clemence Ygouf (1835-1871) formed Lecellier-Ygouf.

- Son Felix Émile Lecellier (b. 1857) married Marie Louise Laurent (1856-1938).

- Son Émile Joseph Lecellier (1876-1959) may have operated atelier de tourneur et repousser Joseph Lecellier (workshop with a spinning lathe) in Villedieu as of 1926. (His cousin Léon Joseph is the other candidate.)

- Son Felix Émile Lecellier (b. 1857) married Marie Louise Laurent (1856-1938).

- Second son Édouard Michel Toussaint Lecellier (1836-1891) married Elmina Josephine Havard, and I believe they formed Lecellier-Havard.

-

“EL” for Eugene Lecellier? Son Eugène Joseph Lecellier (1864-1931) had two sons who carried the Lecellier name into the 20th century. (See Eugene’s stamp with the initials “EL” on the right, courtesy of reader Annabel S.)

- Elder son Eugène Victor Édouard Lecellier (1898-1937) and his wife, Elizabeth Jeanne Vigla (1898-1973), formed Lecellier-Vigla. This company joined Elizabeth’s parents’ firm, Vigla-Havard, successeur ancienne Havard-Bouillet et Noblet Fils Ainé.

- Younger son Lucien Lecellier (1906-1990) became the successeur to his father Eugène Joseph and formed L. Lecellier, the company we know in the 20th century.

-

- Youngest son Léon Raphaël Lecellier (1846-1926) was an inventor as well as a chaudronnier. He obtained multiple patents for mechanical locks, an important branch of coppersmithing for the maritime and travel industries. I found records in Paris in 1901 of the Société Léon Lecellier et Compagnie, an all-purpose metalworking shop. He married Marie Pitel and had one son.

- Son Léon Joseph Lecellier (b. 1877) may have been the “Joseph Lecellier” of the atelier de tourneur et repousser in Villedieu as of 1926.

Each of these men and women has their story but I will focus on one in particular: Lucien Lecellier, whose work is marked with the L. Lecellier stamp and seems most prominent in the vintage French copper market.

L. Lecellier

Lucien took the reins of his father’s shop in 1931 when Eugène Joseph passed away. Lucien renamed the workshop for himself but retained the notation successeur Eugène Lecellier as was the usual practice when a firm changed hands. The shop was located on Rue de la Pilière in Villedieu. There is not much I can find written about the company so I can only describe what I see in its production. I believe that Lecellier, like Mauviel, was an artisanal operation until the 1960s, when US interest in French copper cookware began to grow. I have found several examples of stamps with “L. Lecellier” and have tried to place them in rough chronological order, but as always, I welcome corrections and amplifications.

Early stamps

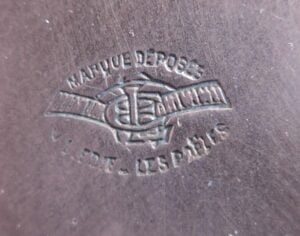

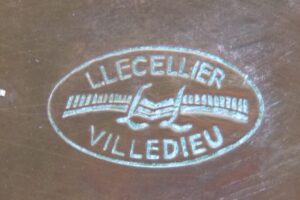

I believe these two stamps are from the firm’s early period in the 1930s.

|

I tentatively place this stamp first based on its similarity to the stamp used by Lucien’s father, Eugène Lecellier. Both stamps have initials in front of some kind of flat object — an open book? A brush? I wish I knew what it was. Whereas Eugène’s stamp has the initials “EL,” Lucien’s stamp has “LL.”

I see this stamp mostly on non-cookware copper items such as vases, lamps, platters, et cetera. Perhaps this stamp was reserved for decorative cuivre d’art as opposed to cookware. |

|

I don’t believe the cross in the center of this stamp is a Lecellier symbol. Instead, I think it refers to Villedieu in general — it’s a Maltese cross, in keeping with the town’s history, and the water jug and bell refer to the town’s two important industries. I’ve seen this cross stamped on other pots on its own or accompanied by initials, which leads me to suspect it was used by multiple poêliers as a symbol of Villedieu origin.

For this stamp, L. Lecellier seems to have borrowed the cross symbol and wrapped it with the name of his company and the words marque déposée — denoting that the firm’s name is trademarked. |

Later stamps

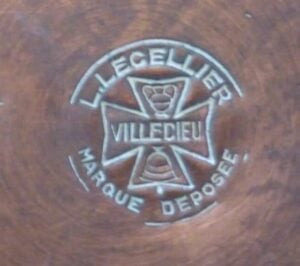

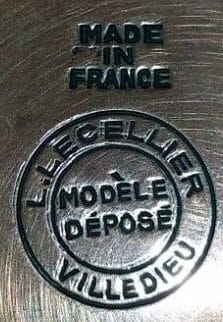

Based on the pans on which I’ve seen them and the presence of the “Made in France” stamp that came into use in the 1960s, I believe these stamps are on pots from the 1960s up until L. Lecellier closed in 1993.

|

This stamp continues the circular motif of the earlier stamp above but replaces the Maltese cross with a drawing of a copper craftsman at work. It’s charming. I think the large wooden column — also shown in the photo at the top of this post, itself taken from the Lecellier workshop– is the comorner, a specialized wooden anvil used in coppercrafting.

I’ve seen this stamp on tin-lined and steel-lined pans, which leads me to conclude that it was used in the 1980s. |

|

This stamp identifies the pot and also warns imitators. Whereas earlier stamps noted that the name L. Lecellier was a marque déposée, this stamp specifies modèle déposé — the design itself is trademarked.

Note also the “Made in France” stamp. Its presence points to 1957 or later, which helps to date the pan. But not only that, the style of the stamp is distinctive to Lecellier — the Mauviel “Made in France” is different. This style of Made in France may be enough to identify a pan as Lecellier. |

Aluminum, nickel, and steel linings

Just as Mauviel in the 1970s and 1980s explored alternatives to tin as a lining for its copper pans, so too did Lecellier.

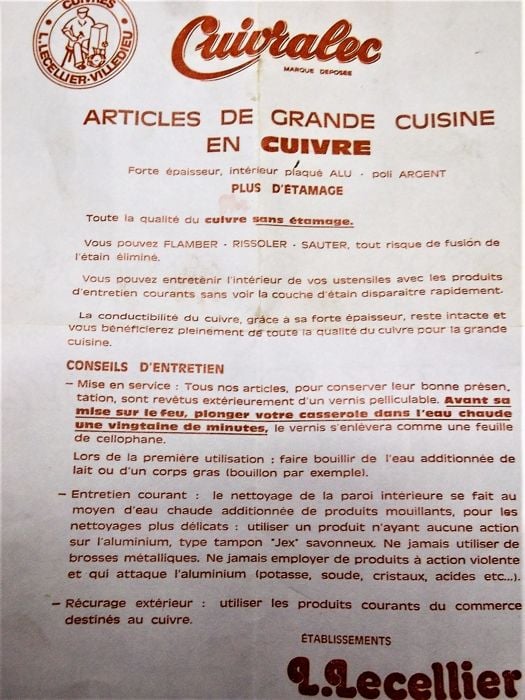

Cuivralec: Copper and aluminum

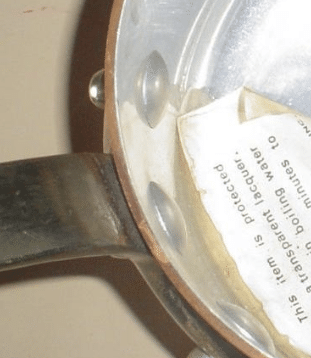

Lecellier trademarked this name in 1976: “Cuivr-” is for copper, “al” is for aluminum, and I believe “lec” means electroplating. (I don’t know if Lecellier actually electroplated the aluminum onto the copper but I know it’s physically possible to do so.) According to the product insert, the primary advantage of this product is plus d’etamage — “no more tinning.” The interior surface was described as poli argent, “silver polish,” likely referring to the mirror finish and not implying the presence of any metallic silver.

Note how thick the copper is and how thin the layer of aluminum. Some copper-aluminum pans are in reality an aluminum pan with a thin layer of copper plate on the exterior, but not these. The majority of the pan wall is copper and the aluminum layer is perhaps 10% of the thickness. Aluminum is an excellent conductor of heat but it is also soft and reactive to acids; if you are willing to accommodate these qualities in your cooking, a Cuivralec pan would be an excellent choice for thick copper cookware.

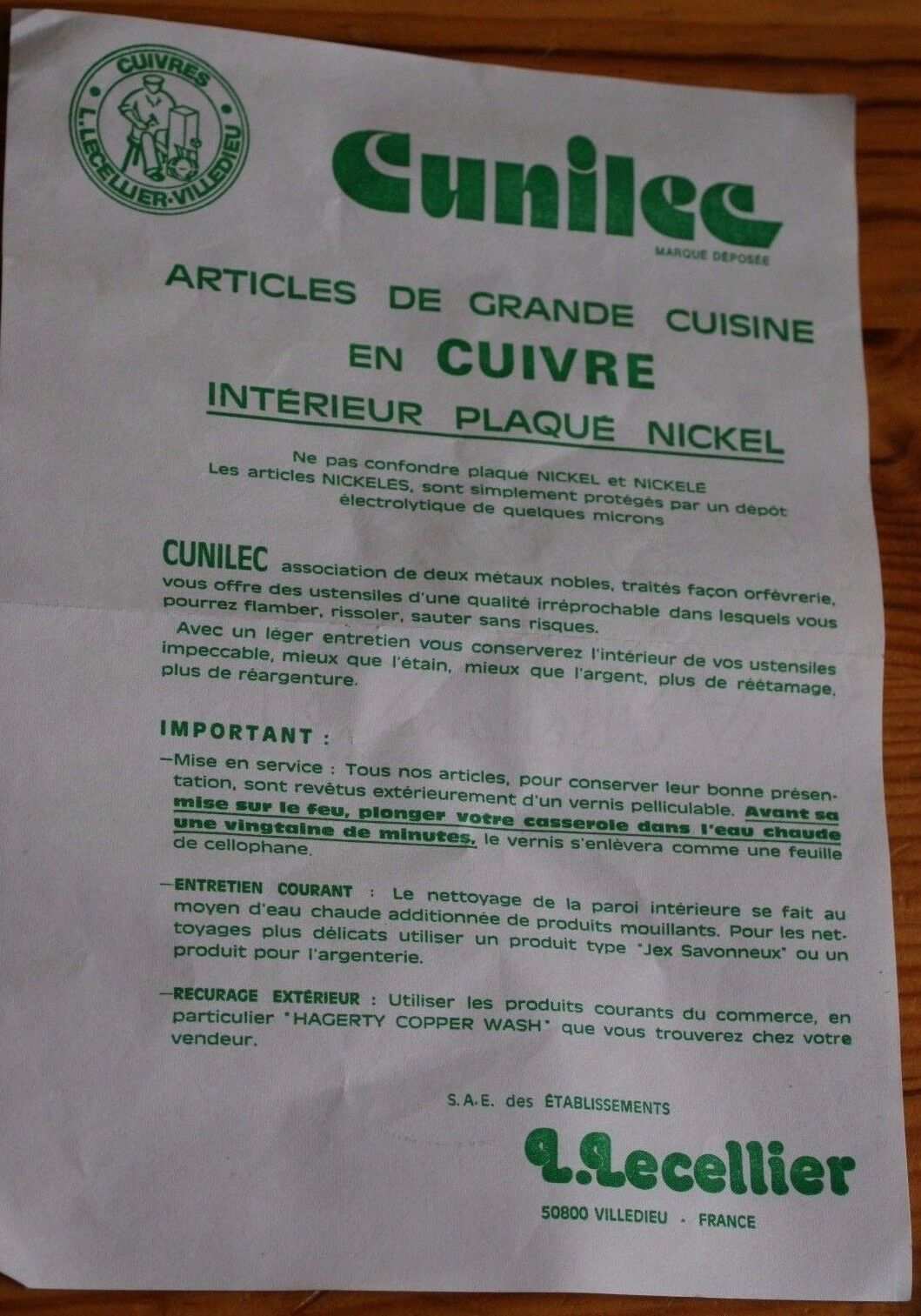

Cunilec: Copper and nickel

Lecellier trademarked this name in 1980: the “Cu” in the name means copper, the “ni” is for nickel, and again, “lec” seems to refer to electroplating. (As above, I don’t know whether Lecellier electroplated the nickel to the copper, but the name seems to imply so.) Online sellers chronically mis-identify these pans as steel-lined but if you see this Cunilec stamp on a pan, it’s nickel. (If you’re interested in my opinion about nickel as a lining for cookware, I invite you to read my post about it.)

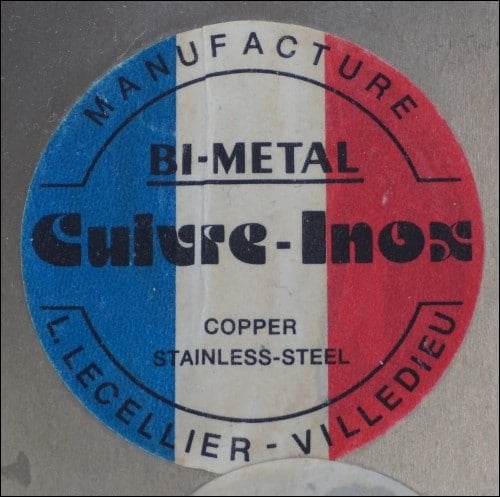

Cuivre-Inox: Copper and steel

L. Lecellier also manufactured copper-steel bimetal pans — or at least stamped them and put a sticker on them that claimed as much. What’s odd is that at least one of these pans also included a Mauviel Cuprinox product enclosure. Could Mauviel and Lecellier have shared manufacturing facilities or have licensed each other’s products?

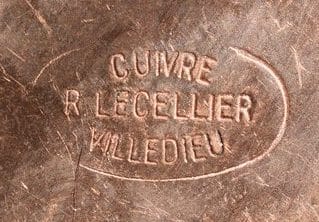

Raymond Lecellier

In addition to L. Lecellier, there is another member of the family who produced copper in the 20th century: Raymond Lecellier at Cuivre de l’Abbatiale (“Copper of the Abbey”) at 45 rue du Général Huard. The trademark for the name was filed in 1981 and the store seems to be open today. I’m not sure what connection this enterprise has with L. Lecellier and I haven’t yet located Raymond Lecellier in the same family tree.

|

This stamp is the only example I’ve found. I’ve seen it on saucepans as well as on accessories and souvenir items. It could be a store stamp. |

I hope this guide is helpful to you. As always, I am working from information I can find online and trying to make educated guesses. I welcome any information you can provide.

I have a set of new vintage vintage new Cuivralec L Lecllier Villedieu Copper and Aluminum Pots and Pans, pictures here https://imgur.com/a/MUWZry5 Not sure what to do with these, sell at a auction somewhere? Any ideas other than ebay or etsy?

Hey Lane! Those sure are pretty pots. I think eBay or Etsy will be your best bet — they both have some Lecellier pieces already so you can do some price checks. Keep in mind that not all sellers know how to recognize tin vs steel vs nickel vs aluminum so you may have to look closely at the photos to get some comparable prices. But that’s a nice set and the stickers make it clear they’re brand new. Good luck!

Thanks for all the effort in these infos. Very educational, today I bought in market place a cuivralec exactly same as Lane S, but mine is not brand new new but very lightly used. I am thinking if I keep the Patina or not… Dilemma thanks if you can advise

Hey Gus! Congratulations on the purchase! If the pans are for your own use, it’s a matter of personal preference. The copper exterior will tarnish if you cook with them — the heat accelerates the process. I do not clean tarnish off my cooking copper because I use it every day and can’t keep up, and also because I’ve come to appreciate the deep gleam of well-used copper.

If you are considering selling them or giving them away, that’s a different question. Many sellers leave antique pieces tarnished as part of the aesthetic. However, my opinion is that “modern” copper made post-1960’s — like yours — is more appealing to a new owner with a bright coppery appearance. Speaking for myself, when I buy antique or vintage copper, I am comfortable with inheriting the tarnish from its prior life, but when I buy young copper to use in my kitchen I prefer it to be a clean slate, so to speak.

I hope this helps with your deliberations! Enjoy your new-to-you copper!

Any possibility that this is fake? The color is dark brown, and shiny and i tried BaR keeper it didn’t change a thing.

Heya Gus — Send me a photo of the pans and I’ll see if I can help. vfc at vintagefrenchcopper dot com.

For those of you following along at home, it turns out that Gus’s pot still had the original protective lacquer coating! I happen to have the original Cuivralec product card posted on the site with the instructions on how to remove it. Gus was able to soak away the lacquer to reveal the beautiful copper of his second-hand-but-unused vintage pot. Well done Gus!

Can someone help me identify a copper container please?

Hey Jesse! The Contact Me page has a way to send me some photos — I’d be happy to take a look.

Great article VFC, the Lec is for Lecellier possibly?