I’m covering both Benham & Sons and Benham & Froud in the same field guide because the two firms are related.

Some online sources maintain that the companies were separate entities but that is not the case. I was quite fortunate to come across a wonderful writeup on London Street Views with thorough and sourced research that lays out the history of these two firms. I urge you to read that excellent article and the author deserves all the credit and praise for correcting the record. I will restate those facts briefly in the History section below to set the chronology and will focus my own effort on the copper itself.

I am also indebted to reader Roger W., who has reviewed and assisted with research for this guide.

History

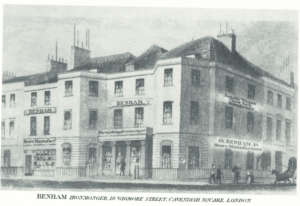

In 1821, John Lee Benham (1785-1864) founded J. L. Benham, Ironmongers, selling products from his father’s blacksmith shop on Blackfriars Road in London. He did well enough so that in 1824 he moved the business to 19 Wigmore Street on Cavendish Square, where he set up his own ironworks. According to a history written by Stanley Benham, “the workshops were in the basement and cellars, the showroom was on the ground floor and John Lee lived on the first floor.”

In 1821, John Lee Benham (1785-1864) founded J. L. Benham, Ironmongers, selling products from his father’s blacksmith shop on Blackfriars Road in London. He did well enough so that in 1824 he moved the business to 19 Wigmore Street on Cavendish Square, where he set up his own ironworks. According to a history written by Stanley Benham, “the workshops were in the basement and cellars, the showroom was on the ground floor and John Lee lived on the first floor.”

He married twice and had eight children — three daughters and five sons. Four of his sons worked in the family business and by the 1850s the firm was a thriving metalworks that had expanded into the neighboring buildings to manufacture bathtubs, stove grate and kitchen ranges, and hot water systems. By the 1860s, the street numbering on Wigmore Street changed, and the family’s sprawling ironworks adopted 66 Wigmore Street as its storefront address.

In 1855, John Lee and his son Augustus (1826-1884) formed a partnership with Joseph William Froud to purchase the R. & E. Kepp metalsmith on Chandos Street. That firm, founded in 1785 by Joseph Kepp, had gained prominence in 1821 by winning a high-profile project: the replacement of the orb-and-cross ornament atop the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

The new ornament made by the Kepps measured 23 feet (7 meters) tall and weighed 7 tons (6350kg). It was well-built indeed — it still adorns the dome to this day — and the Kepps proudly adopted the orb and cross as the company’s logo. When the Benhams and Joseph Froud took over the business in 1855, they renamed it Benham & Froud but kept the orb and cross as the company’s symbol.

Eight years later, in 1863, Augustus and Joseph amicably bought out John Lee’s share of Benham & Froud. John Lee passed away in 1864 at age 79 and his sons James and Frederick took over direction of the firm, by now renamed to Benham & Sons.

Twenty years later, in 1885, James Benham passed away. Frederick made a series of ill-fated business decisions that created financial stress, and after Frederick died in 1891, the family took the family firm public to raise funds. That is when Benham & Sons became Benham & Sons Ltd. However, internal family disagreements continued and in 1907 the firm was reorganized again. The head office remained at 66 Wigmore Street but the manufacturing facilities were moved to more spacious quarters out of the center of London. The two World Wars in Europe created more demand for the company’s products and the firm recovered and established offices in New York, Cape Town, and Sydney. The Benhams sold the firm in 1959, and though the name survived, that marked the end of family management of the firm.

On the Benham & Froud side, Augustus Benham passed away in 1884, within a year of his brother James. The company went public and became Benham & Froud Ltd. The company described itself as a general metalworking company with an emphasis on fine detailed work and had a workshop behind the main shop on Chandos Street as well as a second workshop at 98-99 St Martin’s Lane. In 1906 (some sources say 1913) the firm was taken over by Herbert Benham & Company and relocated to Ramillies Place in Great Marlborough. The last records of that business are in 1924.

The question I’ve always had is, what’s the difference between these two companies? Now that I know their shared history — or rather, that Benham & Froud was an offshoot of Benham & Sons — I am even more curious. How did these two enterprises co-exist?

After poking around for a bit, I have a theory. Benham & Sons was first and foremost an ironmonger and I believe their central focus remained on large industrial products: boilers, heating and refrigeration, gas systems, steam-powered engines for municipal water supply, and the like. I think Benham & Froud was spun off as a coppersmith for the consumer market: smaller, more detailed products with an emphasis on design, that required a different skill set from casting, forging, and engineering industrial machinery.

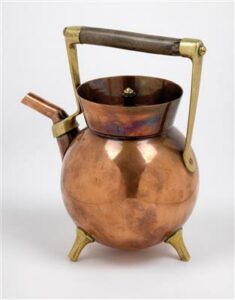

In support of this theory, from 1873 to 1893 Benham & Froud commissioned a series of product designs from Christopher Dresser (1834-1904), an early English designer who produced hundreds of original concepts for housewares, textiles, and ceramics. His 19th century designs were so modern that they are often mischaracterized as Art Deco, but he predated that era by decades. For Benham & Froud, Dresser designed tea kettles, candlesticks, lamps, fireplace andirons, and other household items over a period of twenty years — a substantial collaboration that produced objects of great beauty and surprising permanence.

I think the two Benham firms were complementary, not competitive. There are many examples of copper cookware with stamps from both companies, and I suspect this is because when Benham & Sons won contracts as a “kitchen outfitter” they turned to Benham & Froud to supply a set of pots and pans. But this does not appear to be an exclusive relationship: reader Roger W. has also seen copper with the Benham & Sons stamp that is clearly French in make, and so likely sourced from the continent instead. For its part, Benham & Froud also appears to have sold its copper through a range of retailers including Harrods and Temple & Crook. After reading the history of the two firms and considering the range of copper products carrying their marks, I see father-and-son firms that grew apart over decades but never turned against each other.

And now to the purpose of this post — the copper itself.

The copper

Benham & Sons

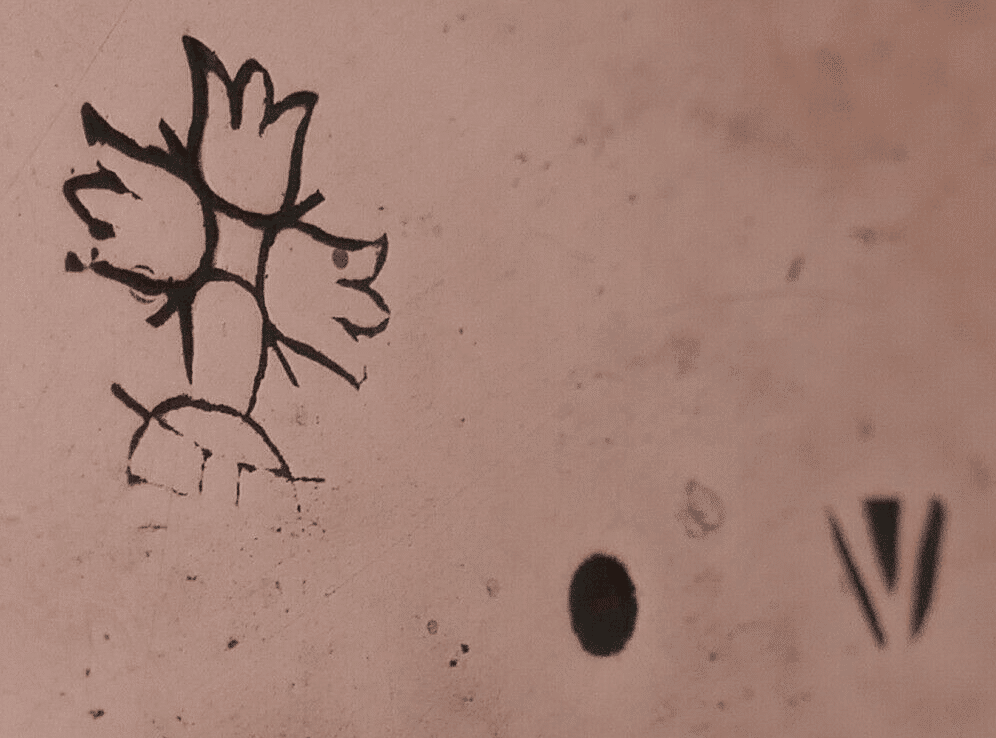

The Benham & Sons mark is the firm’s name encircled by a stylized belt, with the tail of the belt wrapped around and flipped over to hang below. I have seen two versions of this stamp.

This stamp reads “Benham & Sons Wigmore St London” and I believe it indicates production prior to 1891. I don’t know how early this stamp could be; there should be a “J. L. Benham” mark as well but I have not come across it. (If you have an example I would love to include it.) What’s curious about this stamp is that it does not include a street address for the company. Here is a second example of the same stamp that is impressed slightly differently so you have a better view of the left side of the stamp.

|

This stamp reads “Benham & Sons Ltd 66 Wigmore St London” and I believe it is a second stamp used after the firm went public in 1891. The “Ltd” is what gives it away: the company was in private hands until that year. I do not know if there are other stamps after this one. Benham & Sons continued into the 1960s at least. |

Even if the stamp lettering is not clear, you can recognize the difference by the length of the tail of the belt — it is longer on the later version of the stamp.

Benham & Froud

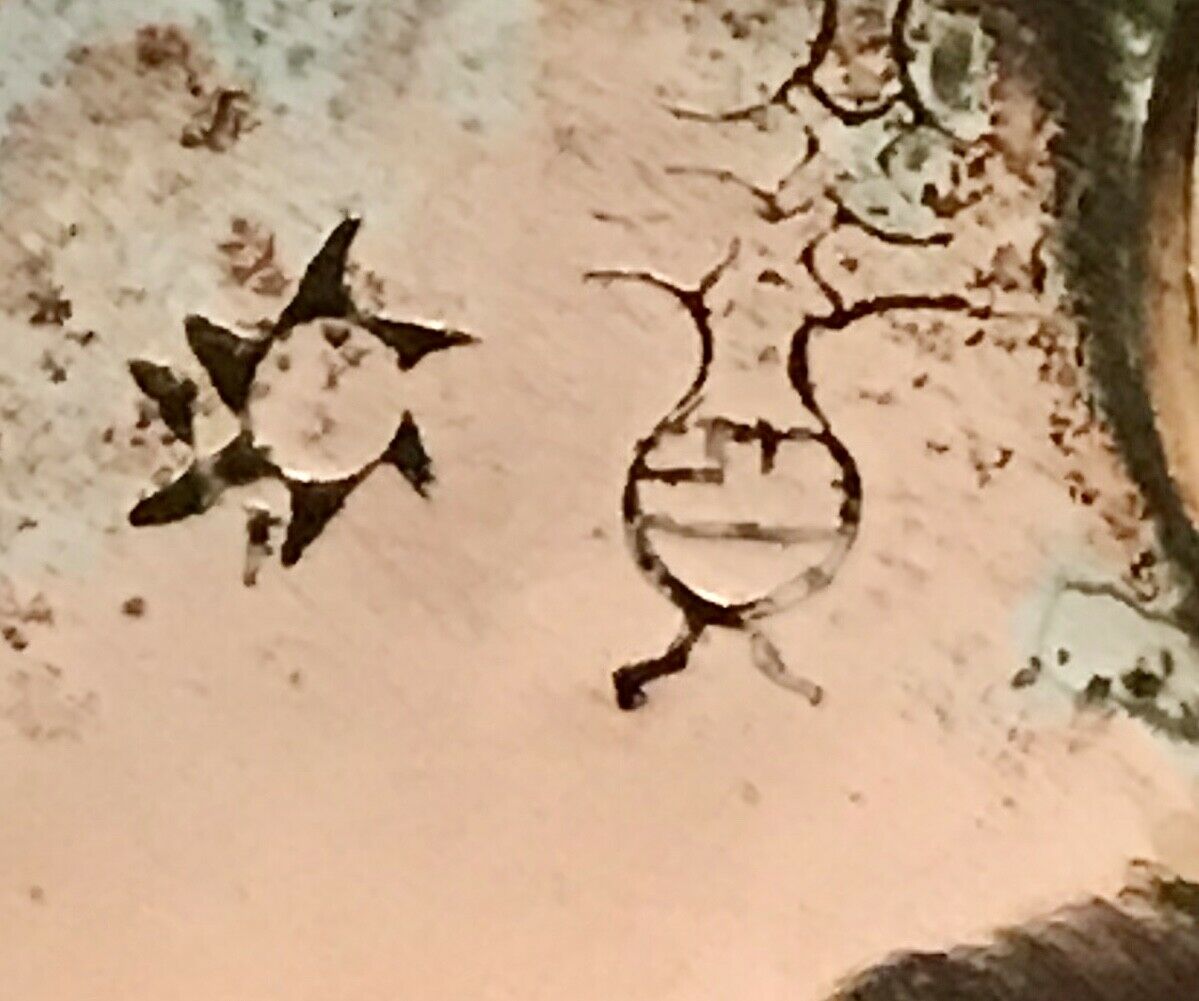

The Benham & Froud mark is the orb and cross design modeled after the ornament atop St Paul’s Cathedral in London. The company was active from 1855 to 1906, and unfortunately I don’t have information at the moment to identify variations in the stamp that could be used to date pieces within that range. (The exception would be Christopher Dresser pieces made between 1873 and 1893.)

The stamp is customarily placed on the base of a piece and is frequently worn away; this particularly clear example is from a decorative tabletop vase. (I suspect the “Made in London” is a 20th century version of the mark, as the orb-and-cross is usually on its own with no wording.)

The orb and cross is often accompanied by a secondary symbol. Oldcopper.org believes that the second mark indicates the specific workshop that produced the piece, and that is a fair surmise given the dizzying array of items the firm manufactured. According to London Street Views, Benham & Froud had two workshops — one at Chandos Street and a second at 98-99 St Martin’s Lane.

I have gathered some examples of the different secondary symbols and made a note of the type of object on which the symbol was placed.

Cookware

Molds

Kettles

Lamps and decorative items

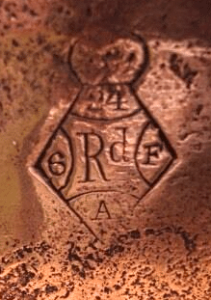

Some items also carried an additional symbol: a diamond shape with numbers and letters within. This is not a Benham mark but rather a Victorian-era trademark registration symbol: the “Rd” in the center means “registered,” and the numbers and letters correspond to the owner or design.

Some items also carried an additional symbol: a diamond shape with numbers and letters within. This is not a Benham mark but rather a Victorian-era trademark registration symbol: the “Rd” in the center means “registered,” and the numbers and letters correspond to the owner or design.

This is a work in progress and I welcome better information on the history of these firms — as well as more stamp examples! My thanks again to London Street Views for their work to organize and untangle the history of these two companies, and to reader Roger W. for review and research contributions.

There isn’t enough space between the buckle and the W of Wigmore. Was the ironmongery so famous that it didn’t need to specify its street number? According to London Street Views, the numbering changed in the 1860s — could the stamp have been left un-numbered to avoid obsolescence?

There isn’t enough space between the buckle and the W of Wigmore. Was the ironmongery so famous that it didn’t need to specify its street number? According to London Street Views, the numbering changed in the 1860s — could the stamp have been left un-numbered to avoid obsolescence?