Reader Kris P. has tracked down some rarities for us.

Says Kris,

I’ve finally put together all the catalogues I could collect. These were mostly sourced from worldcat.org where I signed up and reached out to individual libraries for a reference copy. Most were able to meet the requests without costs, which is fabulous. Only the Briffault catalogue required to pay. Some requests were not able to be met because the catalogues are more recent, e.g. Dehillerin/Matfer catalogues, as they could become potential copyright infringements when a copy is produced. Others were only available in person.

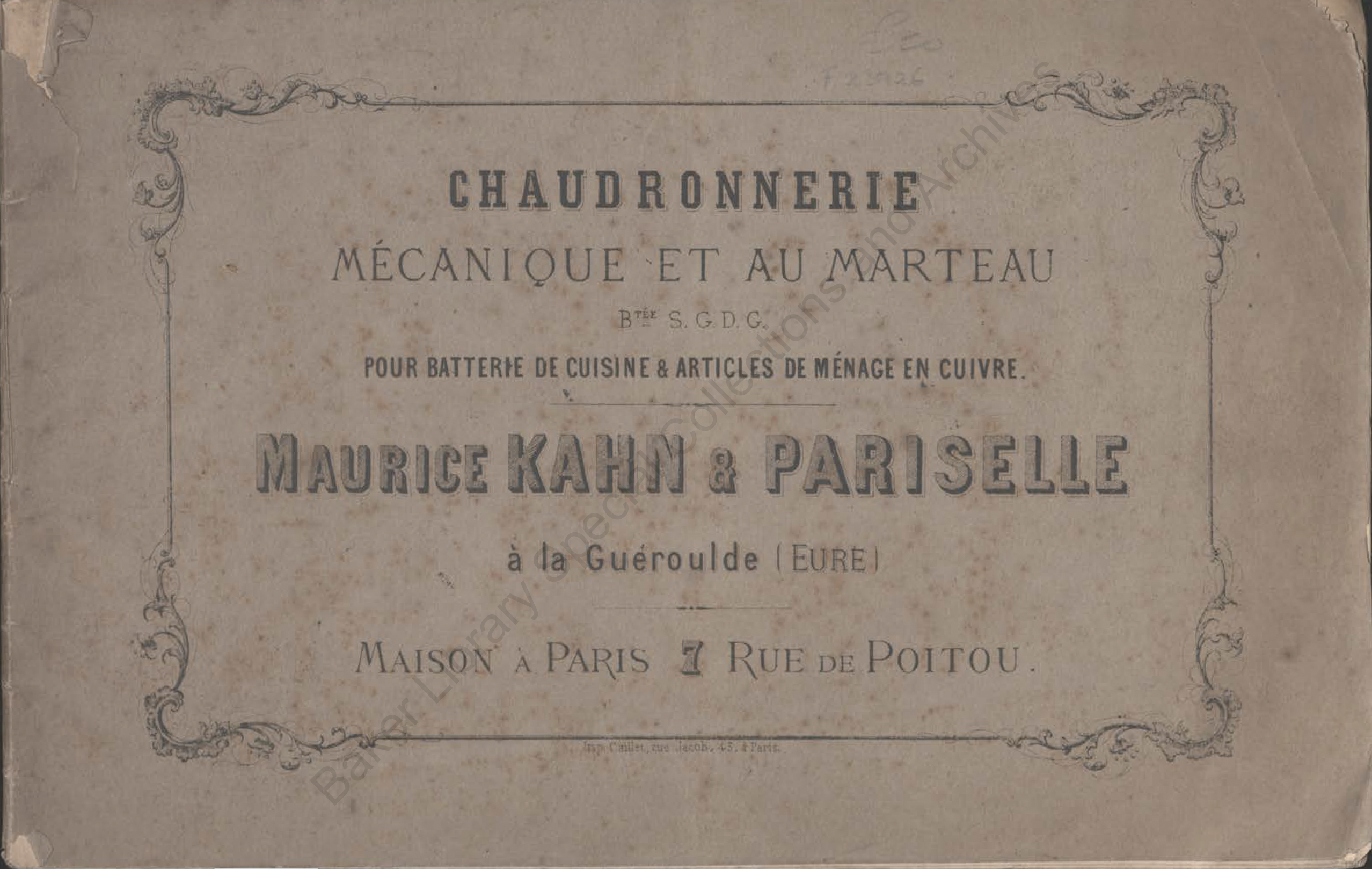

- The 1880 Maurice Kahn & Pariselle catalogue appears to be a manufacturer supplier catalogue, which I have not seen. In the catalogue, page 13/14, you can see what I reference as scrollwork handles and a dog-bone handle as inventory they produce. Reinforces the idea that many chaudronneries sourced their parts from suppliers like this, which means relying on parts, like handles, to identify a manufacturer is not a reliable method (as we know).

- Briffault catalogue also shows quite a bit of pieces which do not have dog-bone handles although it’s quite difficult to tell from the catalogue.

Kris, I cannot thank you enough for these contributions. These catalogs have been invaluable for my research to identify pieces, and I know readers appreciate them as well. I also thank you for your attention to the dog-bone and scrollwork handles — like you I am coming to believe these styles were used by multiple makers. It may well be that the handles are an indicator of age but not of specific provenance.

Readers, please take a look at the Library for these new additions!

- Benham & Sons, 1862

- Maurice Kahn & Pariselle, 1880

- Briffault, 1897

- Duparquet Huot & Moneuse, 1898 and 1907

- Dehillerin, 1961

- Lasnier, undated, but likely late 19th century

These catalogs are priceless! I can’t wait to peruse the Benham & Sons catalog over my morning tea. Thank you!

Where does this guy keep finding these catalogs? Many thanks Kris P.!

Thank you Kris P. and VFC for providing these valuable additions to the library.

What finds – thank you!

Wonderful, will enjoy these when I have time. I did try to look at the Benham one first but the 1956 Gaillard loaded and I don’t know why.

So sorry, Roger. I re-checked all the links and I think they are all pointing at the right things — may I ask you to try again?

Anyone have any information about chariot copper same address as Leon Jean (lJean) on which era..been looking .

Would love to know if this was a collaboration..between makers.

Unfortunately, I could not find a more suitable place for my following commentary.

The Annual Almanacs, yearbooks, weeklies, journals, catalogs and collections listed in the Library are undoubtedly invaluable sources. However, it should be borne in mind that these are publications by publishers such as Hachette and similar commercial companies and not legal publications by public authorities. Genealogical sources are also commercial enterprises. You should check here whether the published data are transfers of entries in the archives of the registry offices or scanned extracts. The latter are of course much more reliable. We have already made the experience with the illustrations in the catalogs that these can often only be understood as a comparatively rough guide and in no way correspond to the precision of today’s product photographs. I think you should interpret all this data, which is up to 150 years old, with a little tolerance and imagination.

The “Archives commerciales de la France” was a newspaper (journal) that appeared twice a week and was available both individually and as a subscription. In 1903, the single issue cost 25 centimes, the annual subscription 20-25 France. The paid entries and advertisements were commissioned by the companies themselves. Small businesses, e.g. tradesmen, were usually content with single-line entries, while larger companies placed correspondingly larger advertisements. I do not know whether there were also free entries, as was the case with the telephone directories of the past. “La Sûreté du Commerce, Société anonyme”, a Parisian joint stock company, was responsible for the distribution and acceptance of entries of all kinds (1903).

Since I realized that these company entries are not documents in the strict sense, I have been able to deal better with contradictions that I have come across from time to time during my research.

Examples:

During my extensive research on the coppersmiths Jean and Jean Alfred Leon Tendrerie (father and son), I found the civil registration that Leon died in Paris on January 13, 1900 at the age of only 44. His father Jean already died in 1881. So how can it be that the business entry “Leon Tendrerie, chaudronnier” was still to be seen almost regularly until 1919? However, no successor of the same name is known. Leon Tendrerie’s widow died in 1917. In fact, pans, lids and molds were marketed with both the first business address 60 rue l’Arcade (1856-1907) and the second address 44 rue Pasquier (1904-1919). This means that goods were still stamped “L.Tendrerie” for up to 19 years after Leon’s death. Who ran the business, who made the pans?

Another example: Saillard is listed in the business archives as “étameur”. However, several stamps on various pans bear the designation “Chaudronnerie Saillard”. Only the addresses match. So who can you trust, the stamps or the entries in address lists and advertisements? Personally, I tend to trust the stamps, at least in this case, as they are an original source from the workshop. In addition, Saillard could have been sued for misrepresenting his profession.

Francis Lejeune also did business at the same address. The pans bearing his stamp only show his name and address, but no profession. A pretty good argument that Francis Lejeune was probably a merchant with a store.