Think all iron handles are the same? I sure did.

Val Maguire at Southwest Hand Tinning was telling me about the beautiful wrought iron handle on an antique pot she was restoring. I thought “wrought iron” was a fancy term for cast iron, so I asked, “You mean cast iron handle, don’t you?” I was wrong, of course, and Val was generous and patient enough to educate me: not only are wrought and cast handles quite different, there are actually three types of handles the appear on French copper from the 19th century and into the 20th. It’s not just interesting to know this, but useful as well: the type of handle on a piece tells you its approximate age but also something about the skill and sensibilities of the maker.

Quick history

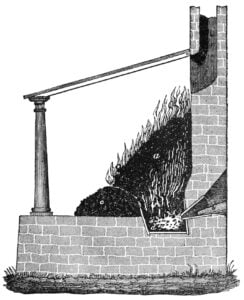

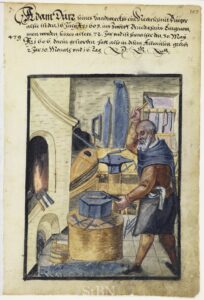

Iron ores occur naturally in the earth, and “making iron” is the process of smelting: heating the ore to separate the elemental iron from unwanted impurities called slag. In Europe up into the 1500s, iron was smelted in a bloomery furnace running at around 1300°F (700°C). The goal was “wrought iron” that was soft enough to be worked with hand tools (that is, wrought), which meant keeping the carbon content low. Too much carbon produced useless “pig iron,” iron locked in a cage of carbon too brittle to be wrought. The smelter’s task was to produce a “bloom” of mixed iron and slag that was then pounded with a hammer to drive the last remnants of slag out of the metal. (Ever seen a blacksmith hammering iron while sparks fly? Those sparks are hot slag flying off the surface.) When the iron was acceptably pure, the smith formed it into bars or ingots that could be reheated and re-wrought into useful objects.

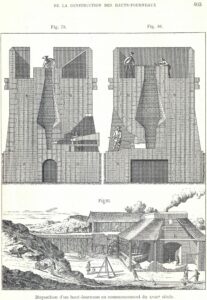

The next major innovation came in the 1500s: more heat. The blast furnace used bellows to blow air into the smelting chamber to increase the temperature substantially. By the 1700s, harnessing water power and then steam power to drive larger bellows improved it further. A blast furnace could exceed 2000°F (1100°C) at which temperature the unworkable high-carbon pig iron could finally melt.

This was the beginning of the era of cast iron in Europe: melting and molding what had been brittle trash iron into resilient useful shapes. (Thank Henry VIII of England for this — his orders for cast-iron cannon and shot for his armies spurred innovation to meet the demand.) But blast furnaces were huge and so expensive to run that only a few cities in Europe could sustain them. Most smaller cities and towns continued operating bloomeries to produce inexpensive wrought iron.

The industrial revolution in the 1800s brought a new factor to bear: engineering. By adding different substances into the furnace, the smelters discovered how to control the iron-carbon blend much more precisely; new furnace designs were smaller, hotter, and less expensive to run. By the 1890s, blast furnaces had supplanted bloomeries and every major city in Europe had iron foundries capable of producing copious amounts of low-carbon wrought iron, medium-carbon steel, and high-carbon cast iron.

Handles

The progress of European metallurgy from the 19th century into the 20th shows up in the evolution of handles on French copper pots during this span of time. Based on consultations with Val and my own observations of the craftsmanship I’ve seen on a wide range of pans, I’d like to suggest this timeline.

| Base metal | Shaping technique | Recognize by… | Era estimation (France) |

| Low-carbon wrought iron | Forged (compression): Concussive hammering on an anvil | Flatness, spread baseplate, rat tail hanging loop | Early 1800s to mid 1800s |

| Wrought (tension): Stretching and pulling with hand tools | Smooth surface, soft contours, asymmetry | Early 1800s to very early 1900s | |

| High-carbon cast iron | Cast with molds | Filing marks, symmetry | 1880s to present |

Again, my era estimations are just that — an observation based on what I have seen. There will be outliers: early and late examples of each style, dependent on each maker’s access to handles of different types (and desire to work with one style over another). Please use this as a guideline but not an arbiter.

Wrought iron

The term wrought means worked, and wrought iron is a grade of low-carbon iron that is malleable and ductile enough to be worked with hand tools. This is the primary grade of iron that metalsmiths used in Europe until the late 1800s: the bloomeries produced lumps of iron and slag that were hammered (that is, wrought) to expel the slag. The wrought iron was formed into bars and ingots that could be easily transported, reheated, and re-wrought into finished products.

There are two types of handle made from wrought iron: those shaped by hammer blows, which I will call forged handles, and those shaped by stretching with hand tools, which I will call wrought handles.

Forged handles

This type of handle was shaped by compression: the iron was held against an anvil and hit with concussive hammer strikes.

Characteristics

Flatness

The clearest indicator of a forged handle is its flattened profile. It’s made from bar iron cut to size and then hammered to spread and thin it as needed. The little pot below is an unusual example because the hammering is so obvious to the eye — many forged handles have a smoother surface than this one.

Rat tail hanging loop

Another key indicator of a forged handle is a “rat tail” hanging loop: the end was thinned into a slender “tail,” curled around into a loop, and then pounded to re-join the handle.

Spread baseplate

Another characteristic of a forged handle is a spread baseplate: the iron was flattened, sliced, and spread apart into two flanges to create more surface area to rivet to the pan body.

Custom forms

I often see forged iron handles on unusually-shaped pans or as patched-on repairs. This is one major advantage of forged iron: the smith can cut and shape the metal to the exact right size and shape to fit the need, be it the stubby legs of a lechefrite or Band-aid style reinforcements to a handle baseplate. In this sense, forging represents the ne plus ultra of handwork: every forged handle is custom-made to the pot.

Age estimation

Based on what I have observed, forged handles were used on French copper cookware up until the early 19th century, but by the 1850s had been supplanted by wrought handles.

By and large, forging was a pre-industrial manufacturing technique in Europe. Every village blacksmith was an expert in the techniques of forging metal, be it iron for horseshoes, precious steel for swords, or sheets of copper for cookware. Before there was such a thing as a copper cookware industry in France and Europe, there were thousands of blacksmiths and itinerant tinkers creating, repairing, and recycling pots and pans wherever they happened to be.

In antiques catalogs and online marketplaces, copper and other artifacts with forged iron hardware that have survived from this era are often described as “primitive” — a term intended to characterize skilled hand-craftsmanship that is beautiful and resilient even if it lacks the pleasing visual symmetry and clean lines of industrial production of the later 19th century.

Wrought handles

This type of handle was shaped under tension: it was heated to make it pliable and then stretched and bent with hand tools. I believe the handle on this lid is an early wrought handle, perhaps 1830s-1850s or so; while it has something of the flat profile of the forged iron handle I show above, it looks quite different. The graceful contours and smooth surface are characteristic of a wrought handle, which has never been struck with force but instead stretched and curved into shape.

Characteristics

Smooth texture and rounded contours

The most marked characteristic of a wrought iron handle is its smooth surface texture. The iron retains the soft contours of its semi-molten state because it has not been planished with a hammer. There are no sharp edges — the baseplate meets the copper in an uninterrupted curve; the inside surface of the hanging loop is smooth. The iron has not been struck, sliced, or sanded.

Graining

Wrought handles have fine lines in the metal, most easily seen on freshly restored pieces. The lines come from remnants of slag in the wrought iron. When the iron is stretched or bent, the bits of slag leave visible dark streaks called grains. Look for graining in the regions of the handle that have been manipulated by the smith: the curve from the baseplate to the handle shaft, or along the shaft where it has been lengthened.

Punched or rat tail hanging loops

A punched hanging loop was made with a hand tool that pierced the metal and enlarged the hole. A punched teardrop-shaped loop have a characteristic V-shaped notch where the punch was rocked out of the hole.

The two wrought handles below have rat tail loops. You can see a faint seam where the loop rejoins the shaft of the handle and subtle distortions in the metal where it was manipulated into the loop shape. The metal forming the loop is rounded and the inside of the loop is smooth.

Age estimation

From what I have read, wrought handles first appeared on French copper in the early 1800s and by the 1850s had replaced forged handles. The beginning of the end for wrought handles was the 1880s and the last examples I have found are super-sized restaurant pieces of the 1900s.

Wrought handles mark the peak of the “golden age” of French copper: the era of the rise of French cuisine, the relative peace and prosperity of the Belle Époque, the flowering of Paris as the center of European culture — factors that also fueled the French copper cookware industry. In this increasingly competitive market, the smooth voluptuous curves of a wrought iron handle on a copper pot would be an instant sign of quality and luxury, like fine Corinthian leather for a car’s interior. If the chaudronniers were sourcing and riveting wrought handles for their products, it was because their customers were willing to pay more for them.

But advances in metallurgy changed the economics. It is significantly easier and faster to cast and machine-form iron components, and new inventions at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries made it less expensive as well. Why continue the time-consuming process of hand-working wrought handles when cast handles could be made to look identical at a fraction of the cost and effort?

Cast

This handle was molded: the metal was melted, poured into a two-piece mold, and left to solidify into its final shape.

Characteristics

Seams and filing marks

The mold for a cast handle is in two pieces and the casting process can leave a visible line called a “mismatch” or “shift” along the seam where the two pieces of the mold were joined. Based on what I have seen on cast handles, the seam runs around the outer edge of the baseplate, up the sides of the handle shaft, and around the inside and outside of the hanging loop.

The smith seeks to reduce the appearance of this seam with a grinder or a hand-held rasp. These file marks, often mostly clearly visible around the baseplate, and are a clear indicator that the item was cast.

If a cast iron handle has been carefully filed, the marks may be less visible. What’s key here is to look for flattened planes along the upper contours of the baseplate where it narrows to form the handle shaft. These flat planes were produced by machining.

While it’s relatively easy to smooth the baseplate and handle shaft with a grinder or rasp, the hanging loop is a different story. There is very little space inside that loop for a tool and so oftentimes the seam here is left raw. Look closely at the seam inside the loop and you can see extra material called “flash,” “fins,” or “burrs”; run your finger around and you can feel it.

Surface texture

My observation is that the surface texture of cast handles can vary quite a bit: some have a visible graininess while others have a smooth surface to rival a wrought handle. My guess is that this has to do with the specific method of casting. If the foundry used molds made of metal, then the finished piece would have a smooth surface; if the method was sand-cast, then it would leave a grainy appearance. Says Roger W., “The majority of modern cast iron is lower quality with an internal texture like one of those honeycomb candy bars so it is thick and heavy to compensate for how brittle it is. For some reason I don’t know, much coarser sand is used for the mold making the surface very rough. Often no attempt is made to improve the casting other than rounding off of sharp edges.”

Age estimation

Based on what I have seen, cast iron handles for French cookware appeared in the 1880s and by the 1900s had supplanted wrought handles. It is simply so much more economical to cast hundreds of identically perfect handles in a day rather than laboring over pieces one by one, and cookware handles are cast in iron, steel, or brass to this day.

But Val notes that some makers of cast iron handles sought to make them look like wrought, most notably by adding a V-notch to the hanging loop. Look closely at the hanging loop of 20th-century Mauviel pans and you’ll see it — a deliberate vestige of the wrought handle era.

Conclusion

When you’re evaluating a piece of iron-handled antique or vintage French copper, take a look at the handle — it will give you a clue as to the era in which the pot was made. Forged? Think early 19th century, maybe even earlier. Wrought? Mid-19th to early 20th. Cast? Late 19th to the present day.

One area where this information can be particularly useful is if you’re trying to estimate the age of a piece for sale. Many sellers claim a piece is “early 1800s!” when to my eye it’s clearly much later. The handle can be a giveaway here: if it has the liquid look of a wrought handle, it very well could be mid-1800s to the 1900s, but if it’s cast, it’s most likely 1880s or later.

I’d like to extend my profound thanks to Valerie Maguire at Southwest Hand Tinning. She is not only a talented tinner and restorer but also a student of history and a generous teacher. I’m very grateful for her time to help me with this post and also for the care she’s given to several cherished antique copper pieces.

A word on cast brass

While European smiths did not cast iron in quantity until the 1500s, they had been casting brass well before then. Discoveries about the chemical properties of zinc in the 1700s made it easier to produce high-zinc brass and encouraged an industry to cast brass instruments and devices, especially for maritime use to resist corrosion. Cast brass handles appear on French cookware throughout the 19th century to the present day.

Brass handles on older pieces can have fine surface scratches. TJFRANCE tells me that these marks could be left by the wire wheel that a 19th or early 20th century retinner used to abrade off carbonized or polymerized oils from the brass; modern retinners in my experience are more gentle!

Brass has qualities similar to cast iron: it is strong but brittle. I have bought a few pots with cracked brass handles and on more than one occasion a handle has broken off during rough-and-tumble shipping. Fortunately, the break can be repaired with silver solder.

Sources

Medieval Iron and Steel — Simplified; Bert Hall, Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, University of Toronto.

Hi,

are you sure that first J. E. Gaillard pan has a wrought handle, it looks like a well finished high quality casting to me and I am almost certain that the second example punched hanging loop is a casting.

19th century and even early 20th cast iron tends to be better than modern production. The sand used in molds was finer and greater care taken to machine surfaces. There are enthusiastic collectors who will pay surprisingly high prices for antique cast iron cookware because old skillets were better made hence easier to season.

Cast iron can warp, twist and deform in unpredictable ways as it cools so it should not be assumed that irregularities mean handmade.

Hey Roger! Let me take a close look at that saute. I have a hard time telling early cast from wrought handles and it’s quite possible I’ve made a mistake. I have your email address — may I send you some photos and ask your help to straighten it out (no pun intended)? Also, I’m interested in examples of cast handles that *have* been warped/etc if you have any. And as always, thank you for the corrections — I am always grateful for help to make the site more correct for readers.

Very interesting and informative article. Thanks for posting. Is there a book on copper pans developing here? If not you should certainly consider it.

The knowledge of copper pots is constantly expanding at VFC! In particular, I find the numerous image examples very vivid and helpful. Thank you. Unfortunately, I still haven’t fully understood the wrought handles production process. Even my efforts at Wikipedia to learn more about forging didn’t make me any smarter. Does stretching and pulling require a higher temperature than the compression technique (forged) or is the wrought technique comparable to isothermal forging?

The iron industry had a profound impact on landscape. Until 1709 when Abraham Darby began using coke to fire his furnace charcoal was the only fuel. The ancient forests of England were felled to supply ship building and feed furnaces. Examine the frame of any old building and it is easy to see signs that the only available wood is reclaimed from decommissioned ships. Humble dwellings were wattle and daub (woven sticks and mud/dung) what little furniture most people had was made from hedgerow wood.

Mainland Europe had much larger area of forest but industrial areas must have been stripped just the same.

For me it is hard to imagine that brass handles should be brittle and therefore more prone to breakage. Finally, these handles were also used on particularly large and heavy pots. If handles broke, I think this is a casting error. Brass like other cooper alloys are widely recognized for their excellent resistance to stress corrosion cracking and corrosion fatigue. Therefore copper alloys are frequently used for applications requiring superior mechanical strength.

Martin, I think casting errors and flaws are likely in antique pieces. It’s also the case that the alloy “brass” can vary significantly in its components, with corresponding variances in strength and malleability. The breakage I’ve experienced is always in the same spot: the prongs between baseplate and handgrip, where the brass is at its most slender. I expect the shipping boxes were not well cushioned and the box was dropped directly onto the handle side, creating a sudden impact force from the full weight of the pan.

I’ve been researching copper cookware and am wondering why most pieces have iron handles with just a few (none tin-lined) having brass handles. My preference is admittedly aesthetic but I’m also puzzled as to why the iron-handled lids must have protruding handles rather than a more compact inverted U. I’ve read that brass handles get too hot to be practical, but I already have to use trivets to move my cast iron pans so these aren’t exactly cool either. Or is it the riveting as opposed to being one solid piece that makes the difference?

In fact, aesthetics are probably the reason why some manufacturers offer brass handles. In particular, series of copper pans that are primarily intended for serving are often fitted with them. Even after a very short cooking time, I find it impossible to touch brass handles with my bare hands. Short handles heat up much more quickly than longer handles, regardless of the material.

That makes sense, given the larger quantity of material present to absorb the heat. My problem in addition to it just looking funny was something additional to bump accidentally while working around the stove. But as for being hot, I expect handles to be hot, in the oven or on the cooktop; only if it’s just the pilot keeping something warm could I expect to pick something up with my bare hands.

It is sometimes claimed that handles were also cast from bronze, another copper alloy (copper + tin). Bronze is supposed to be a bit more brittle, but it is the preferred material for bells, where it is subjected to the greatest stress.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bronze

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brass

Martin, I’ve long contemplated a post on exactly this topic. My personal opinion at this time is that bronze has not been used for everyday French cookware, as I have never seen a piece confirmed to have bronze handles. I think Mauviel is the source of the confusion: they have always described the yellow handles on their M’tradition pieces as “bronze” when to my eye they are clearly brass. Who are we mere mortals to disagree? People repeat this authoritative source even against the evidence of our own eyes.

Brass like copper work hardens and decades of small knocks and bumps will do that. I remember reading a suggestion that placing copper in front of a subwoofer and playing bass heavy music would harden it. Brass also age hardens and must be annealed before any attempt at bending.

Roger, that’s fascinating! It wasn’t until I started studying copper and tin that I realized how much metal atoms are able to move and shift, even in the solid phase, and how much of metalworking is concerned with de-aligning and re-aligning the atoms to control the properties of the metal. Sound waves are pressure waves, and it makes sense to me that the concussive pressure could also dislodge atoms!

Roger,

I know something similar from knife makers who proudly report that they found ancient steel, melted it down and forged blades out of it. There would be nothing better than ancient steel. This is certainly a sensible recycling and careful use of the earth’s resources.

Already in ancient times forests were destroyed to build warships with wood. Even after more than 2000 years, the landscape has not recovered, with the goats not playing an insignificant role.

You are right, I had completely forgotten that it was the “goddess” personally who put this bug in my brain. Due to a little handicap, I cannot reliably see the color differences, at least with older alloys. “yellowish brown” (bronze) and “light yellow to red yellow” (brass) are not miles apart. After all, our favorite metal copper is dominant in both alloys.

Martin, I have been mystified by this too and have spent quite some time peering at brass and bronze photos online. Bronze reliably appears to me to be darker and greener than polished brass, but so is tarnished brass. Could some handles that I think are “tarnished brass” actually bronze? I think I need to do a post on this and call upon the collective wisdom of readers with more knowledge and experience!

99,9% of all photos don’t reproduce colors exactly or naturally; quite a few are even grossly wrong. Professional photographers put great effort into determining the color temperature of an object and reproducing it accordingly. I am therefore afraid that it is hardly possible to distinguish between brass and bronze based on photos on the Internet. Any more sophisticated image editing program allows any color manipulation. The question is whether these options have been used appropriately. To unravel the brass-bronze problem we will have to find other ways.

Thank you for doing the research on the different handles. As Roger noted above, it can be difficult to tell the difference between a wrought and well finished cast handle. I have a number of cast iron pans including a few that are pre-Griswold. Those pans have incredibly smooth finishes and are much lighter when compared to more contemporary Wagners or Giswolds. The hanging hook on those pans compare favorably with the punched hooks on the wrought handles. I’d suggest that the handles that are obviously cast are likely on post WWII pans. Pulling from your Villedieu page, post WWII, there was an increase in production/demand for French copper. Increased production along with the assumed loss of skilled labor because of the war means corners were cut. Where once cast handles would have been completely finished now a few file marks was considered acceptable.

Ultimately it doesn’t matter, but combined with the stamps, rivets and other indicators, it helps give us an idea of the age of the pan.

Separately, do you know if copper pans were ever cast? I have seen a couple examples now of saute pans that appear to have a fold in the copper that I’d attribute to a shift in the mold during casting.

Bryan, I think you’re correct — Val mentioned to me that early cast handles were intentionally designed and finished to look as close to wrought as possible, which would entail (costly) extra finishing steps.

Along those lines, does anyone know a blacksmith with historical knowledge of 19th century techniques? I’d love to have an actual blacksmith take a look at some of my photos and tell me how things were made, particularly the wrought handles. I emailed one guy I found online but I’m not sure he’ll get back to a query out of the blue!

And to your second question: I do not know that I have ever seen a copper pan that was cast. I’d love to see a photo of a pan you suspect may have been — may I ask you to email it to me?

VFC, I just emailed it to you.

Hi,

The other thing to keep in mind is that forged does not necessarily mean entirely hand made. When someone says blacksmith’s forge the mental picture is probably a chocolate box imagine of a thatched cottage at the edge of a village, the forge itself nearby with a horse waiting for new shoes tethered outside whilst the blacksmith makes them and a boy works the bellows. The reality was likely to be a small factory with multiple forges and a team labouring away in sweltering heat. Probability is in copper pan production areas handle making is all that they did.

The great majority of pans produced would be of domestic sizes, 14-24cm diameter in 2cm increments and standard shapes so handles in these sizes likely ordered by the dozen or even hundred. If you’re making a one off special then you form it completely by hand but for multiples it is worth having a mold cast. Now you just make roughly shaped blanks and hammer them hot into the mold. A jig to follow means the iron can curved in a repeatable way. A bit of finishing, hot rasping and you have a handle in minutes by which time the apprentice will have the next one hot and ready to work. Water or steam powered hammers are likely toward the end of the 19th century.

Great article VFC and Val! You had me running around looking at various handles to see if they conformed to the dates I’d been told. Thanks.

Hey Sus! Thanks for the comment! This article is going to be a work in progress for a while — several readers have discreetly reached out by email with suggestions to improve it. Check back in a bit for some updates.

I second this motion!

From my personal experience casting, pure copper does not cast well at all, it picks up oxygen very quickly upon melting and unless deoxidized (ie adding tin,zinc, silicon etc ) will produce a casting with obvious bubbles/blemishes and surface defects. It is doubtful that any antique copper pot or handle would be cast of pure copper. A good example is a hand “soldering copper” which is typically a round rod of wrought iron or mild steel with a wooden handle on one side and pure copper cast onto the other. Used by copper/tin/black smiths to solder two sheets via dovetail/cramped seams. Because it only serves a utilitarian purpose it does not have to be beautiful only functional.

Brass may be similar to cast iron in brittleness but there is a difference in thermal conductivity. Cast iron has 52 W/m K @ 20C. Brass has a thermal conductivity of 111, and pure copper about 400. I would expect that the more desirable characteristic for a handle is minimal thermal conductance (but still able to withstand cooking temperatures). In that respect the cast iron handles would take longer to heat up and are an arguably better handle material than brass. What are others’ thoughts? Building on the past and knowing what we know now, what would be the best handle material if the values were: strength, long-life span, low thermal conductivity, cost in a future potential sense? I note Nickel steel with 40% nickel has a conductivity of only 10.

Reference: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/thermal-conductivity-metals-d_858.html

Have you seen examples or wrapped hand made copper handles? I have an example or two..

Hey Ryan! I think I understand what you mean: an all-copper handle made from a long slender strip that is folded under so that it has a seam running the length of the shaft. So yes, I have seen this style — a reader wrote in with an example in Episode 2 of Dear VFC (https://www.vintagefrenchcopper.com/2021/11/dear-vfc-episode-2/). Take a look at that example — is that what you mean? Do you know anything about the history?

The handle on my unidentified, 7″, square dutch oven emanates from a side, not a corner. I haven’t see a similar handle: 4″ long, it has a diamond -shaped hole for hanging. Can you shed any light on this?

Hey Dave! The Contact Me page lets you send photos. I’d be happy to take a look!

I think what you saw may have been a lockseam. I am a hobby metal caster that also hand forges a little. Pure molten copper is thick like molasses when molten and picks up oxygen too fast to be cast into anything anyone would find useful. This is one reason we add small amounts of deoxidizers, there a many for specific purposes today but in antiquity they would be mainly arsenic (found already in the copper ore that was mined), zinc sulfide and metallic tin. They all make copper fluid at a much lower temperature, less reactive, and “castable”. At least into something that looks less like a copper/copper oxide sponge. Arsenical bronze/Copper is one reason we have a “copper age”. Arsenic changes the properties of copper drastically in such small quantities while still remaining the color of copper. Whereas zinc and tin in small amounts immediately make it more of a golden color. Copper in it’s pure metallic form is what makes it a good conductor of heat and electricity while also being ductile enough to be able to shape it for the purpose intended.

Regarding the cast brass handles, and more specifically the fine scratches sometimes seen, I’m starting to think that these are the result of pre-assembly finishing, much like the filing seen on cast iron handles, rather than a later cleaning step. In reviewing the pans that I have, it is most obvious on two particular pieces, both of which are remarkably unused and are unlikely to have been subjected to numerous rounds of maintenance.

Firstly, if these scratches were the result of some cleaning process with the handle already riveted to the copper pan body, there would surely be evidence of similar scratches to the copper around the handle, and also to the rivet heads, yet I see neither.

https://imgur.com/a/Ypsisbg

This Legry soup pot has the same scratches on the handles but no corresponding scratches to the copper. It is clear the copper hasn’t been overly polished over the years as you can still clearly see the file marks from cleaning the dovetail seam.

https://imgur.com/a/w5m8h5x

The example seen here on this G J Journel plat a sauté is even more convincing. If you look closely at the second picture, you can see the scratches are applied over the whole surface of the handle, right to the edge of the base plate, which would be almost impossible to do after the handle has been attached.

I suspect the reason these scratches are only seen on a few older pieces, is that for the majority, decades of cleaning and polishing has worn them away, and that for many pieces, the « scratched » state is in fact the original state.

I also wonder in what state a handle was supplied from the foundry to the copper smith, and whether the chaudronnier might dedicate some time in the production process to the finer finishing of handles before assembly. There are countless subtle differences in handles that may have come from the same casting mould that could be accounted for with differing approaches to finishing and/or polishing of the supplied castings.

I’ve never seen such scratches on a later piece, and I suspect that is completely down to the more common use of machine polishing during manufacture.