Sharp-eyed reader David A. found it. He emailed me about a listing on Etsy for an unusual 30cm sauté:

Specifically, look at the mark. It appears to be a du Louvre mark overstruck on an Allez Frères mark (most visible by the word “Établissements” and the narrower oval). Do you think that this could indicate that Mauviel produced both lines and that someone made an initial mistake on the mark? The handle and rivets appear to be du Louvre.

David, I think you’re right — the layered stamps on this pan appear to link it to the same maker, Mauviel. Evidence like this doesn’t come along very often so I bought the piece so I could examine it more closely and document it.

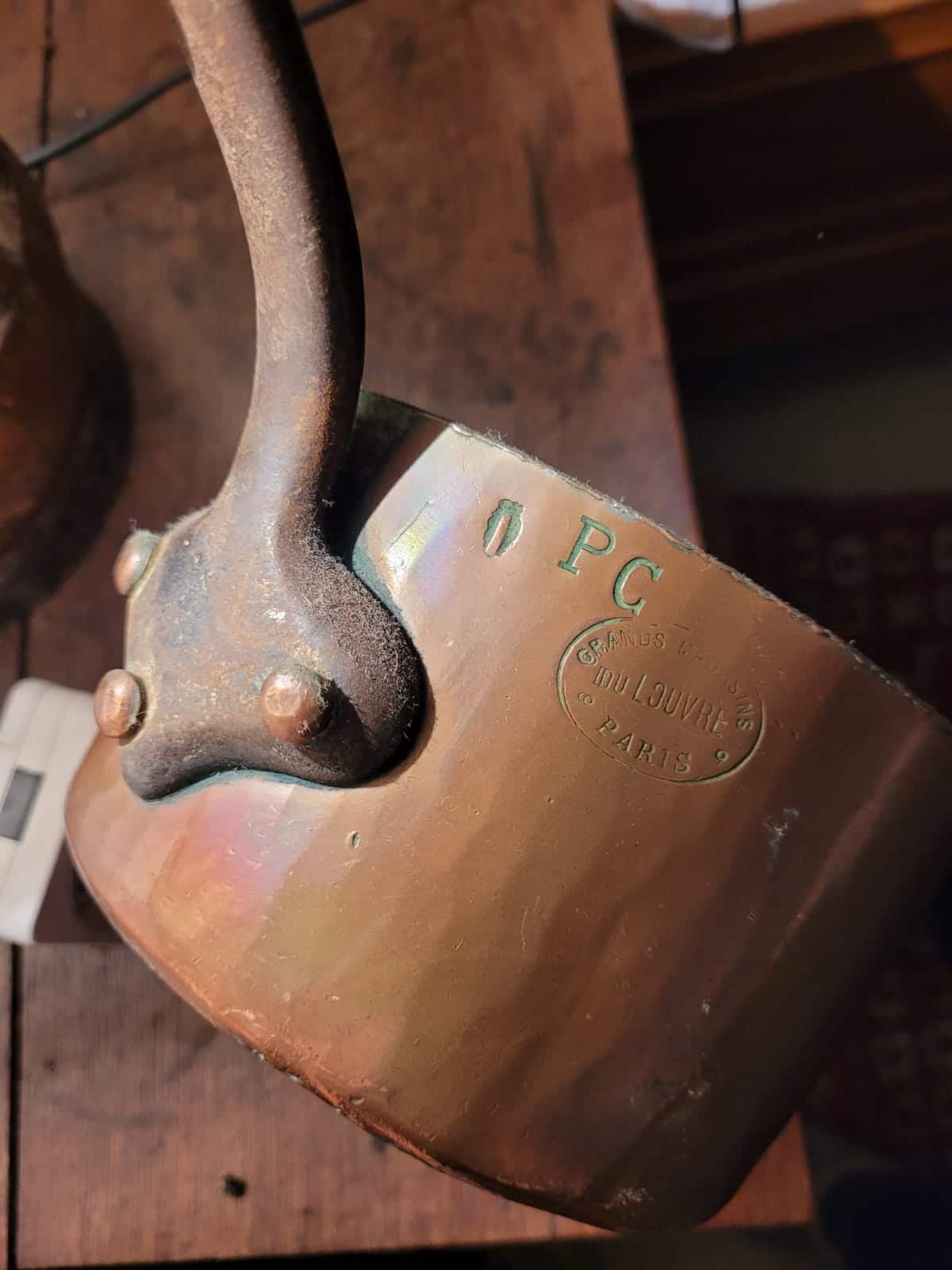

Let’s start with a good look at the stamp.

I see three strikes: a double strike of the Grands Magasins du Louvre mark, and also a third faint strike of the Allez Frères mark. Below are two clear examples of each stamp from other pieces of mine.

Allez Frères and Grands Magasins du Louvre (GML) were retail stores in Paris, not coppersmiths. Those marks are store stamps put on by the chaudronnerie that made the pieces. According to Thomas Larham, Mauviel-Gautier Frères (the ancestor of today’s Mauviel) made copper for GML, but up until now I haven’t been able to figure out who made copper for Allez Frères.

But this pan suggests an answer.

| Type | Tin-lined sauté in hammered finish with cast iron handle fastened with three copper rivets |

| French description | Sauteuse étamée et martelée avec queue de fer munie de trois rivets en cuivre |

| Dimensions | 30cm diameter by 9.5cm tall (11.8 by 3.7 inches) |

| Thickness | 2.2mm at rim |

| Weight | 4072g (9 lbs) |

| Stampings | “Grands Magasins du Louvre Paris”; “Établissements Allez Frères Paris”; 30 |

| Maker and age estimate | Mauviel-Gautier Frères; between 1887-1908 |

| Source | Etsy |

This is a really lovely pan. It is between 2 and 2.2mm thick at various points around the rim but it feels bottom-heavy in the hand. My 30cm brass-handled GML sauté has the same dimensions and rim thickness but is 700g lighter; I think that service à table pan is a true 2mm throughout, while this one is fort and thickens to 2.5mm in the base.

It’s in pretty good physical shape. It has been restored and retinned at some point, but not recently — I did not choose to send it for another restoration in order to prevent any further polishing of the stamp, but in truth I don’t think it really needs it. It’s a little bit out of round but the rivets are tight and the iron handle is free of rust and corrosion. The tin inside is darkened and aged but doesn’t have the dusty oxidized look of neglect. To be quite honest, I’d give it a good hot wash with soap and water and consider it fine for cooking.

The handle baseplate is the distinctive GML shape. In the photos below, compare this 30cm sauté to the 22cm GML sauté in the middle and the 22cm Allez Freres sauté on the right. The similarity of the two GML baseplates is immediately obvious. But note also the arrangement of the rivets: the GML baseplates have wide-spread rivets, while the Allez Freres rivets are set in a narrower triangle shape.

The different Allez Frères and GML rivet patterns disprove the competing theory that this was an Allez Frères pan re-made into a GML pan. Swapping out handles would be straightforward were it not for the different arrangement of rivet holes. An Allez Frères pan’s rivet holes would need to be patched and re-drilled for the wider spread of the GML pattern — not an impossible task, of course, but one that would leave undeniable traces. But if you look at the inside of the pan you can see that this is not the case. The two side rivets are cleanly drilled with no patched holes to be seen. My assessment is that no Allez Frères handle was ever attached to this pan.

The conclusion I have drawn is that this pan was shaped and stamped for Allez Frères, but before it was drilled for its handle it was re-purposed into a GML pan. It could have been a mistake: perhaps the workman grabbed the wrong customer stamp, and realizing his error too late, corrected it with a couple of more emphatic GML overstamps. Or it could have been intentional: perhaps the GML order of 30cm sauté pans was one short, and this as-yet-undrilled Allez Frères pan was a hasty substitution.

But both scenarios lead to the same conclusion: the same workshop made pans for both stores, and that workshop was Mauviel-Gautier Frères. I compared the time periods when these stores were selling copper, and the overlap is 1887-1908, which makes sense for the construction I see on this pan.

What do you think? Is this enough evidence to assert that Mauviel supplied both stores? Let me know what you think in the comments. And my thanks again to David!

PS. The GML stamp on this piece is actually a little different from the others I have: it has two little circles on either side of the word “Paris.” I have three other GML pieces with good clear strikes but none of them have these circles; I took a closer look at Thomas’s GML pieces, and it looks like his 12cm and 16cm saucepans also have the circles, but not the others in his collection. Well, now we know there are at least two versions of the GML stamp. Two time periods? Two makers? It would help to have more examples. If you have a GML pan with the stamp with the dots, I’d be grateful if you’d get in touch so we can see if we can figure it out. Thank you!

Update: Reader Stacer M. came to the rescue — here’s her unrestored GML saucepan with the version of the stamp with dots. The handle baseplate shape looks the same to me, but the rivets look a little larger than on other pieces I’ve seen. Readers, what do you think?

Another great find! It does lead one to conclude that Mauviel did indeed supply both of these Paris stores. I have a Grands Magasins saute pan which does not have the little circles. It would be nice to know what time periods these two stamps covered.

Another interesting tessera to complete the mosaic!

Good morning all,

I hope everyone is doing well in these difficult times.

To begin with, can someone tell me where the source that Mauviel supplied to the Grands Magasins du Louvre in the late 1800s, early 1900s came from?

Then, it doesn’t appear that the Grands Magasins du Louvre supplied the copper pots with the “Louvre” handles before the early 1900s, unless someone has a catalog that shows otherwise?

Regards, T.J.

Hi TJ — The info that Mauviel made copper for GML comes from Thomas Larham, who wrote a guest post about his collection called “Mauviel’s Masterpieces.” He is the only source I have for that info, and while I haven’t been able to corroborate it, neither can I dispute it. Please take a look at his post — if you have different information I’d be very happy to correct the record. Thank you!

Thank you ! Yes I would like to ask these important questions to Thomas.

Hello, thank you for this information. I read his article which shows someone passionate. I will read asking these questions directly in his topic.

In the meantime, I invite you to read my last article which will certainly help many enthusiasts to understand many things.

https://francelorrainecollection.fr/Fundamental-Bases/

To all Copper Lovers!

Regards, T.J.

Oh ! Topics says “Comments are closed.” ???

Hi TJ! Thomas’s article was written some time back and the comment system closes comments after a period of time. I’ll re-enable comments for the next couple of weeks if you’d like to return and leave a comment on that post. Thank you!

Thanks for this, TJ! It gives us much to think about!

After reading the article on TJ’s website his arguments struck me as plausible at first glance. But after some thought, I missed verifiable evidence to support his assumptions. Just as TJ himself rightly desires evidence to support Thomas Larham’s claim that Gautier-Mauviel Freres were the supplier of copper pans for Grands Magasins du Louvre. Without this evidence, I fear, there will be even more confusion. If I understand TJ correctly, ultimately, it is not possible to reliably determine by whom and where a pan was made, regardless of which stamp is embossed. Everything is possible??

This conclusion goes a little too far for me. Certainly these assignments are difficult and sometimes controversial, but I think the approximations, as they are made here at VFC, should still be possible.

There is no doubt the history of the production of copper pots is extremely complex. The mere fact that there were nearly 100 manufacturers and retailers underscores this assumption.

Since the contemporary witnesses, who were able to give us a deeper insight into the production methods and the interdependence of the craft businesses and retailers, have long since passed away, only records, books, articles and advertisements in newspapers, annual reports and documents of various kinds can shed more light on this story throw. However, only a very limited number of these sources are available in digital form, if at all. Without access to specialist literature in libraries, you will hardly get any new knowledge. Of course, this requires a good knowledge of French, a willingness to travel and a lot of time.

Thankfully, VFC lists some of these sources in the library section. However, some research remains tedious. Sometimes I worked with these sources for many hours and still couldn’t find anything useful.

A highly recommended source is John Fuller’s book “Art of Coppersmithing – A Practical Treatise on Working Sheet Copper into All Forms,” the 1901 edition of which I was able to purchase as a reprint. The processes are not only described in words and with an “awful” amount of mathematical formulas, but are also illustrated with numerous drawings of the facility and equipment of the workshops, the tools, the manufacturing processes and the results.

In addition, I recommend every enthusiast to watch videos of the handicraft production of copper objects on YouTube. I was very impressed how a craftsman could create a complex shape with hundreds or even thousands of hammer blows.

TJ points out the theoretically possible origins and aberrations of a pan. Unless his opinion is supported by evidence, we should not make the exception a rule.

Hello Martin, thank you for this message.

A simple example that requires no proof:

The DEHILLERIN house.

Let’s take a random year, 1905.

It has its own manufacture in Paris and other manufactures in Villedieu.

Which pots come from Paris, which pots come from Villedieu?

What stamps are applied in Paris, what stamps are applied in Villedieu?

How do we work in Paris, how do we work in Villedieu?

Regarding these sentences:

“However, only a very limited number of these sources are available in digital form, if at all …. Of course, this requires a good knowledge of French.”

You should know that there are many online sources concerning culinary boilermaking. Including for artisanal or industrial manufacturing techniques. And you are right, the subtlety of the French language greatly complicates research.

Writings from the 1700s and 1800s perfectly explain all the stages in the manufacture of culinary boilermaking, in French.

On Youtube, there are a lot of videos that show, in some countries, a way of tinning and making copper pots that were once ours. It’s exciting, you are right once again.

Let us not forget an important thing, when in Paris, industrial evolution was advancing rapidly, in hundreds of villages, the hammer remained the main instrument.

The time lag between a large city and a village could be several decades. When on one side, in 1850, we already stamped a pan in 1 minute, in one piece, on the other side we had to work several hours with a hammer to make a pan of the same type (so to speak).

And despite that, we could find these 2 types of saucepans on sale at the same time, in the same store.

In the world of culinary boilermaking, the industrialist has the means to invest in modern machines and can become rich. The small craftsman can work for 40 years in the same way while always remaining poor. This will not prevent him from reselling its manufacture to a Parisian shop which also sells more “modern” copper pots.

I know that everyone would like the objects to be well listed, well placed in specific dates of manufacture. It’s something that would work for everyone. Historians, sellers of ancient objects …

But the reality is far from that.

Very often one should not say: “18th century copper saucepan”. The reality would be more: “Copper saucepan made as in the 18th century”.

The same products have been made for decades. The same images of copper pots have been used in advertisements, catalogs of a multitude of stores and manufacturers, also for decades.

I’m not saying it’s impossible to date when all the elements come together. But making a separation of eras for this or that type of production is a real challenge.

This is why, very often (not always) it would be easier to store the pots in periods such as:

– Before 1850

– After 1850

– Between 1900 and 1940-50

And even then, we would not always be right.

Finally, I added a photo gallery of 2 splayed sauté pans in my subject:

https://francelorrainecollection.fr/Fundamental-Bases/

At the very bottom of the article.

Can you watch them and tell me your first impressions?

A big hello from France!

Regards, T.J.

Martin, I replied to your first big message forgetting to reply to the second, sorry.

Thank you for letting me know what evidence you need on what opinions so that I can respond to you.

Good night.

Regards, T.J.

Hi, T.J., I have been trying to get in touch with you a few times over the last two months or so via email, has your email changed? Hope everything is alright

Joe

Hello Joe, the last few months have been very complicated with the corona virus! Between taking care of the family, grandmother and the problems related to all this, I was very little at home to take care of my own business. Sorry! Now we are once again confined! But I am at home now and am more available. Regards, T.J.

I will reach out to you via email. Prenez soin de vous !

Hello TJ, thank you for your further explanations. Since Sunday belongs to my family, I will answer in more detail later.

Here is just my spontaneous impression of the photos of the two Windsor-style pans: You probably want to use these photos of pans made very differently to show that both pans could be made at approximately the same time.

Best regards

Hello Martin, you are right, this Sunday we are also eating as a family, restricted because of the confinement. But we are still going to abuse the good things in the kitchen!

For the photos of the 2 pans, your spontaneous impression is almost correct. But that’s not quite it. And the word “could be made” should rather be “are made” in the sense of certainty with evidence.

But without thinking of a trap or anything “twisted” tell me what you would think of each of these 2 copper pots. I also invite all those who wish to do the same.

I have wanted to talk about John Fuller’s book for some time and I believe the opportunity has come thanks to this discussion. You will understand my reasoning a little better and perhaps realize that you yourself have in your hands some evidence that you are looking for without really realizing it. I keep you informed.

In the meantime, I wish you and all the readers here a good Sunday and especially a good family meal!

Regards, T.J.

Bonjour TJ, good morning at all. Monday, Monday … and some problems are still unresolved.

Of course, there are countless digital sources that deal with the manual or machine production of copper pans. The technical side isn’t the problem. However, I am not aware of any sources that provide information about the business relationships and customs of the “copper scene” in France, particularly in the period from 1850-1940. How can you prove your daring assumption that in principle every craft producer and even every DIY enthusiast from Villedieu or another town could sell its goods, e.g. to Dehillerin and stamp it with Dehillerin?

In your example, “Dehillerin House”, you refer to the fact that Dehillerin also had production in Villedieu. Was this a branch with its own employed craftsmen or which of the numerous local craft businesses produced for Dehillerin? Are there any documents about this and similar business relationships for other brands such as Gaillard? Where can I find out and learn more? I would therefore be grateful if you would make such sources available to us. They are also welcome to be in French, as there are digital translation aids.

Mauviel’s complex business ties over the past 60 years can hardly be unraveled either, since Mauviel itself does not publish anything about it. We all know the American shops that were (and are) supplied by Mauviel, but sold these goods under their own brand names. In Germany, too, an online retailer offered modern copper pans with a stainless steel lining for a long time under the “brand name” “Made in France”. There is not the slightest doubt that these pans were absolutely identical to the “M’heritage” series from Mauviel. I had a few pans myself that I could compare. In terms of price, the “MIF” pans were a little cheaper.

Addition to the Windsor pan riddle: Surely everyone will assume spontaneously that pan A with its toothed bottom, the leaning body and hammered rivets is the older of the two pans. But how do you prove that both Windsor pans were made around the same time?

I can well imagine that traditional and modern manufacturing techniques ran parallel for a while. As you say, not every craftsman could afford expensive press machines. Others might want to stick to manual production out of conviction. Just as mass production as well as “custom made” products are offered in parallel in many areas today.

In theory, it is also conceivable for me that Dehillerin offered pans that were produced in a modern and traditional way and stamped with their own logo at the same time – but only within a short period of time. I suspect that a traditionally manufactured pan would have quickly become a “shelf warmer” (shopkeeper, dead article, slow seller) in direct comparison to modern productions and would have slowed sales. You don’t make sales and profits in such shops with rarities. Most customers still prefer the more up-to-date products.

I too would like to hear the opinions of other readers on this complex subject.

Complement: I doubt that small factories could survive for any length of time if they continued to produce according to gear (dovetail) technology. At most, pans completely driven with a hammer may have found occasional fans. When I visited Villedieu about 25 years ago on a trip through Normandy and Brittany, I was able to marvel at such purely handcrafted copperware. Mazzetti still works in this wonderful way in Montepulciano / Italy today. I think it is more likely that the small businesses obtained machine-pressed raw materials from a factory, which they then reinforced and embellished with hammers and added bought in handles (after all, not even Mauviel makes handles). That´s how the “Pierre Vergnes” manufactory still produces today.

But everything I have written in this context is pure conjecture. So I would be very happy if someone could prove the structure and cooperation in the “copper business” from 1850-1950 with concrete contemporary documents. Opinions are good, evidence is better.

Bonjour Martin,

“Of course, there are countless digital…………………. and stamp it with Dehillerin?”

Because it’s been that way since the industry has existed. If I live in Marseille and want a maker from Villedieu to make casseroles for me and I have a large order from England or Paris, I am not going to ask Villedieu to send me the casseroles to Marseille for that I stamp them and then send them back to England or Paris.

In the past, like today, for subcontractors, regardless of the areas of manufacture, they have to have a way to mark products on behalf of those for whom they work, right?

Without forgetting a very important thing, the transport of the 1850 was not that of today. All the more reason to simplify things even more in those distant times.

How long to go from Villedieu to Marseille? By the Atlantic Ocean, then by the Mediterranean. Then from Marseille to England by sea. Or to Paris by rivers or land? Imagine …

“In your example, “Dehillerin House”, you refer ………………. are digital translation aids.”

I don’t think it was a branch. I rather think it was one or more subcontractors. With, why not, someone from DEHILLERIN permanently on site. But this is only a guess. Certainty is the factory that manufactures for DEHILLERIN in Villedieu.

The relationship between Maison DEHILLERIN and Villedieu is easily found online. Knowing that when the DEHILLERIN house announces that it has manufacturing facilities in Villedieu, it already also has its manufacturing workshops in Paris, information which can also be easily found online.

The relationship between Parisian boiler houses and Villedieu is the very basis to know when you want to study French culinary copper pots. It is a fundamental element. You should know that everything, absolutely everything, that is made in boiler making in Villedieu is already visible and available inside Paris in the 1800s in stores specializing in this field. And this since the end of the 1700s! Parisian professionals would not even need to travel to Villedieu to choose.

I will discuss this subject in my next book on the GAILLARD house.

The reality is not to know with which house of Villedieu to work DEHILLERIN, GAILLARD, JACQUOTOT, etc … The reality is that all large houses which had to ensure large quantities of copper pots have necessarily worked with Villedieu.

“Mauviel’s complex business ties over the past 60 years…………………. …….pans were a little cheaper.”

On the contrary, I would say that it is simpler, there aren’t many manufacturers left from the 1960s on. And detecting those that Mauviel has supplied is often quite simple (I say often, not all the time).

“I can well imagine that traditional and modern……………..still prefer the more up-to-date products.”

This contradicts the book by John FULLER Sr.

He describes a workshop, visited in 1884, which has been working since at least 1844 in an artisanal way, by hand, hammer, rivets. He wrote his book in 1893 assuming that the workshop is still like in 1884 and we can even assume a little (or a lot) afterwards?

I deduce, 50 years minimum of manual labor. The development of stamping machines, which really began in earnest in the 1850s and even more afterwards, did not prevent this workshop from working. And it’s not a little short time, it’s 50 years.

Here is a proof that the work by hand can very well be done in the “modern” world.

Let us not forget an important thing. If, for example, a workshop in Villedieu in 1870, modernized and decided to make pots in series thanks to stamping machines, there are still independent workers. These workers can continue to work by hand for themselves, but not only. They can be suppliers of one who has modernized. So everyone is happy.

“Complement: I doubt that small factories could survive for any length ……….That´s how the “Pierre Vergnes” manufactory still produces today.”

My answer goes with the one above.

“But everything I have written in this …………………………. are good, evidence is better.”

When I say something, it’s that I have already compiled a ton of concrete contemporary documents. It is for this reason that I allow myself to speak about it. When I make a guess or give an opinion, I stipulate it.

Talking about the cooperation in the copper trade of 1850 is the equivalent of putting several big books on your table. Dig in and take what you need. It is very long, very tedious. Then I have to compile the information and so I can talk about it. This topic can be the equivalent of 2 or 3 pages when finished. But you can’t imagine the time spent doing this job.

On the other hand, asking where the information from MAUVIEL for the Louvre department stores comes from can be very fast. An invoice from Mauviel to Magasins du Louvre? Info in a catalog? Really very fast.

Voila, we will finish with the 2 flared sauté pans!

“Addition to the Windsor pan riddle……But how do you prove that both Windsor pans were made around the same time?”

Martin, you stay on the idea that these 2 splayed sauté pans were made around the same time.

But as I told you before, that’s not quite it.

The “A” pot dates from 1885-1895.

The “B” pot dates from the 1860s.

Voila, since I said it and no one can prove the contrary, can we say:

“Here is that ‘B’ pot, look at this beautiful 1860s build!” ?

In the same way that we can say that the pots of the Grands Magasins du Louvre were supplied by the house MAUVIEL? In reality I am neither for nor against this statement. I just want to know how it is justified.

Personally I can justify the date of my 2 splayed sauté pans. Not with an opinion or a supposition but with concrete elements.

I will let you meditate on this question and I will come back to these 2 splayed sauté pans later.

Good night all !

Regards, T.J.

TJ, how did you date these two pieces so precisely?

Good morning all,

The pot “A” is from the DEHILLERIN house, 1 rue Montmartre in Paris, the date of which could be further refined to 1885-1893.

Pot “B” is from PERSONNE house in Paris. This very large culinary boiler house ceased its activities in 1870. It was by buying 1 rue Montmartre from GAULTIER in 1885 that DEHILLERIN became the successor of PERSONNE house (Les Cuivres de Cuisine, Volume 1 : La Maison DEHILLERIN PARIS).

Regards, T.J.

Hi TJ — I took a look at the two pans in the photographs on your page. My first impression is that A doesn’t look like Paris or Villedieu work to me, and the dovetailing looks like a repair. B has the Villedieu/Paris aesthetic with which I am familiar and has a beveled edge on the base that I associate with pre-WWII craftsmanship.

Hello ! The answer for the 2 splayed sauté pans is in a message for Martin.

Regards, T.J.

Hi T.J.

I would not be comfortable putting an absolute date on any pan unless there is a stamp which pins it to a particular time. I think pan A could be as early as 1860 or feasibly as late as 1920. Pan B could be 1880 up to 1940 though in each case most likely near the middle of the range. There is clearly an overlap especially if A is a late & B an early example of the production method employed for each.

It will not be a surprise to most that an given pan is unlikely to have been made by hand of the master whose name is stamped on it but rather it is house of. Martin has used the analogy of an old master painting and of course many of these were studio products were assistants filled in elements not at the center of the picture.

If a large proportion of manufacturing was not done in house, do you think it makes sense to pay a price premium for a pan stamped by a famous maker? The right stamp can mean a tenfold increase in price over a similar or even better unmarked piece.

Hello Roger, I answer for the 2 splayed sauté pans in a message from Martin.

You are right, some will want to give full price for a stamped pot. If a pot is not made directly by the brand but by its subcontractor, I will say that it is not important if the quality is present.

In fact, the cook knows what to choose and he does not choose a stamp. He chooses a quality pot. Then, the collector will be the most impacted by the stories of stamps.

The ideal is to have a pot of high quality and for even more pleasure, with a stamping! It doesn’t matter who made.

Regards, T.J.

Bonjour TJ, thank you for your detailed statement and explanations. I will think about it. Now I’m looking forward to your Gaillard book and hope to find out more about the history of this house and the manufacture of copper ware in France. Further details and sources of information will certainly be listed here, as is customary for specialized books (nonfiction books).

Regards

TJ, thank you for that information. How do you know these pans are from Personne and Dehillerin? Are they stamped?

Good morning,

Yes, the pots are stamped (deliberately hidden for this little experience). I’m having trouble getting my image gallery to work. I can display once in large screen and then the gallery stops working and I have to reload the page. Please tell me if you also encounter this problem? You can see stamps now.

https://francelorrainecollection.fr/Fundamental-Bases/

Regards, T.J.