The stamps tell the story of this lovely railway pan.

| Type | Tin-lined saucepan with brass handle fastened with three copper rivets |

| Dimensions | 26cm diameter by 14.3cm tall (10.2 by 5.6 inches) |

| Thickness | 3mm at rim, likely thicker in base |

| Weight | 4600g (10.1 lbs) |

| Stampings | R CARS PADD; BTHS; P; ST GEORGE on body and handle; Smith & Matthews |

| Maker and age estimate | Smith & Matthews; late 1920s |

| Owner | Martin |

When Martin sent this pan to Stephen Pearse at Newlyn Tinning for refurbishment, Stephen’s immediate reaction was, “Ah — a railway pan!” I am glad I am not the only one with goofy enthusiasm for these pieces. The golden age of European copper cookware coincided with the peak era of luxury train travel and it is fun to imagine a cramped and bustling railway kitchen slinging copper pots about as the chefs prepared haute cuisine for glamorous first-class passengers. These pans made for service on European railways worked harder than most — with no room to spare in the kitchen, every pot had to pull its weight. The ones we find today are often battle-scarred with decades of dings and scratches, but they are also heavy-duty, high-quality survivors.

This one is a beautiful example — it’s an English Smith & Matthews saucepan belonging to copper aficionado and talented photographer Martin.

It’s a gorgeous piece, isn’t it. Stephen Pearse at Newlyn Tinning did a great job with the restoration but this pot had a lot going for it already. Take a look at the hammering — there is a distinct aesthetic here. Compare this irregular pattern to this brass-handled saucepan, this stewpot, and two smaller pieces, all early to mid-20th-century French make. The French style is a more regular pattern of small hammer-strikes like the scales on a fish, while this pan is in a more chaotic and naturalistic style. I’m sure the craftsman who laid down these strikes harbored no lofty artistic pretensions, but looking at it now, it seems to me to have a beautifully organic disorganization, like weathered tree bark.

The brass handle looks French at first glance. The archetypal English iron handle baseplate shape is the inverted arrowhead as on this Jones Bros. saucepan, but this handle’s baseplate is an elongated oval in the French lozenge style. That said, this brass-handled English Leon Jaeggi bain marie (also from Martin’s collection) has the same baseplate shape. Could it be that on English copper, only iron handles had the arrowhead baseplate while brass handles had the broad lozenge?

Baseplate aside, the rest of the handle does not look French to me. The handle shaft takes a slight bend coming off the baseplate but then extends in a straight line with no curvature. My two iron-handled English pieces — the aforementioned Jones Bros saucepan as well as this Lee & Wilkes Windsor — also have dead-straight handles and I wonder if this is another element of the English aesthetic.

The hanging loop is a simple circle, not the French teardrop (nor the keyhole shape of English iron handles, either). This may be unique to Smith & Matthews but I can’t find another brass-handled pan to which to compare it, and so I do not know for sure.

The base of the pan has been given some hammer-strikes to help toughen the copper. The outside edge between base and sidewall is a smooth curve — the sign of a machine-pressed pan. (Copper this thick would be very difficult to bend by hand.)

The interior rivets are flat and flush-set. I have previously associated this flat-head style with 19th century handmade rivets but I am coming to question that assumption as I learn more about craftsmanship during this time. The outside rivet heads have been given a multi-faceted finish with hand-hammering.

I’d like to take a moment to appreciate the work that Stephen Pearse at Newlyn Tinning did for this restoration — the tin is quite smooth and catches the light beautifully. (And of course Martin’s skill with his camera captures it perfectly!)

Martin measured the rim of this pan at 3mm but at 4600g (10.1 lbs) it is quite heavy for its diameter. To put that in perspective, here is Martin’s pan alongside a few others I have measured:

| Item | Diameter (cm) | Height (cm) | Thickness at rim (mm) | Weight (g) |

| Modern-era Mauviel | 24 | 14.5 | 2.7 | 3972 |

| Antique Dehillerin | 24 | 13 | 3.4 | 4370 |

| Antique Lefèvre Frères | 26 | 15 | 2.5 | 4052 |

| This pan | 26 | 14.3 | 3.0 | 4600 |

There is more copper in this pan than its rim measurement would suggest, and it must be in the lower sidewalls and base. This is exactly where you want thick copper — the base is where the pan receives heat from the stovetop, and a greater mass of copper in this area ensures that the heat will be captured and quickly distributed across the floor and sidewalls. What that means for cooking is that this saucepan is ideal for simmering as it will eliminate hot spots and scorching even in thick sauces.

My assessment is that this is an early 20th century piece that combines machine-powered construction with hand finishing. The pan was formed with a machine press — not surprising, given its high thickness — and in such way as to leave much of the mass of the pan in the base and lower sidewalls. It was then hand-hammered across its base and sides to confer some work-hardening to the copper. The external rivet heads have been hand-hammered to give them an attractive faceted look. All in all, the weight and thickness of the piece as well as its hand-finishing make this a high-quality pan.

Now that we have looked at the pan’s construction to get an idea of what kind of piece it is, let’s look at its stamps. This one has a fantastic array and Martin and I have researched them together.

Here are the stamps, the information we’ve pulled together from each one, and the story we think they tell about this pan.

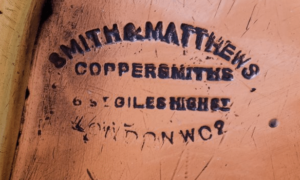

This is the Smith & Matthews maker’s mark with the address 6 St Giles High Street (that is, High Street in St Giles parish) in London, WC2. It has been difficult to find information on this company and I have only been able to string together a few dates and locations. This is the Smith & Matthews maker’s mark with the address 6 St Giles High Street (that is, High Street in St Giles parish) in London, WC2. It has been difficult to find information on this company and I have only been able to string together a few dates and locations.

The earliest mention I see of Smith and Matthews in London is in 1882, but it is not at this address — instead it is at 3 Little Compton Street. The first Smith and Matthews at 6 High Street in St Giles parish shows up in 1891 in a census record for Thomas W. Matthews, coppersmith and kitchen fitter. Thomas is listed again at that address in 1914, and the firm was still at 6 High Street in Bloomsbury (which had merged with the neighboring St Giles parish) in 1945. The next listing I see is in 1963 with the establishment of “Smith and Matthews, coppersmiths” at 30 Eastbourne Terrace London W2 6LF, which was subsequently liquidated in 1984. This suggests to me that this pot could have been made between 1891 and 1945 — possibly earlier, possibly later. But this is a good starting point. (Please note that reader Roger W. suggests that this is a store stamp and that the actual maker is Benham & Sons of Wigmore Street in London, founded 1817 and continuing into the 1960s. As evidence, the brass handles on some stamped Benham pieces are identical to the handle on this pot, down to the circular brass hanging loop. Given the extreme scarcity of S&M stamped pieces, this is certainly possible — perhaps Smith & Matthews “kitchen fitter” had a special contract that called for copper pots as well, and reached out to Benham to provide them?) |

|||

This BTHS owner stamp is what marks this as a railway pan. It represents the British Transport Hotel and Catering Service, a subsidiary of the British Transport Commission from 1953 to 1963. The BTHS operated the on-board dining services as well as hotels near the large rail terminals. This BTHS owner stamp is what marks this as a railway pan. It represents the British Transport Hotel and Catering Service, a subsidiary of the British Transport Commission from 1953 to 1963. The BTHS operated the on-board dining services as well as hotels near the large rail terminals.

Above and to the right of the BTHS mark is the letter P, which we think stands for “Pullman.” George Pullman founded his US company in 1867; by 1874, first-class luxury Pullman cars had made their way to British railways and operated on and off until 1972. The British Pullman Car Company (PCC) was formed in 1882 to operate Pullman cars on British rail lines, first by importing US-built cars and then assembling them at British rail yards. PCC was purchased by British Rail in 1954 during the nationalization of the rail industry after World War II. |

|||

We believe “R CARS” stands for restaurant cars and the “PADD” stands for Paddington, the great railway station in central London. We believe “R CARS” stands for restaurant cars and the “PADD” stands for Paddington, the great railway station in central London.

“London Paddington Station,” as it is officially known, was built in 1839 and expanded in 1854 to serve as the main terminus for the Great Western Railway (GWR), founded in 1833. GWR was the primary rail service out of Paddington until the company was nationalized into British Rail in 1947, which means that this pot likely saw service on a GWR route with Pullman cars. This narrows the timeframe considerably as GWR had only a brief flirtation with Pullmans between 1929 and 1931. According to Wikipedia, The Great Western Railway was reluctant to use Pullmans, considering its own carriages luxurious enough. However, in 1928 the company placed an order for seven Pullman cars — four Kitchen Cars and three Parlour Cars, No’s 252-258 — with construction subcontracted to Metropolitan Cammell in Birmingham. Initially deployed from May 1929 on the London Paddington-Plymouth Millbay service, amongst standard GWR stock within the Ocean Liner Express boat train. From 8 July 1929, the vehicles were deployed to a new train, the Torquay Pullman Limited, an all-Pullman service which ran two days a week between London Paddington and Paignton, stopping at Newton Abbot and Torquay only. Not a commercial success, the train returned for the 1930 timetable as a three-car only service, but was withdrawn at the end of the summer timetable, with the carriages stored at Old Oak Common TMD. A proposal was made to return the full seven car train in summer 1931, but the decision was taken not to operate the service. At the end of the year, the decision was made to terminate the experiment, and the carriages were sold to the Southern Railway, joining their Western Section carriage fleet pool at Clapham Junction. The GWR replaced them in 1932 with the more opulent Charles Collett designed GWR Super Saloons. If our speculation is correct, then this pan may have initially seen service between 1929 and 1931 with GWR before either being put into storage or transferred with the Pullmans to the Southern Railway. (For its part, the Southern Railway used Waterloo Station and not Paddington, so I still think these stamps point to GWR.) |

|||

|

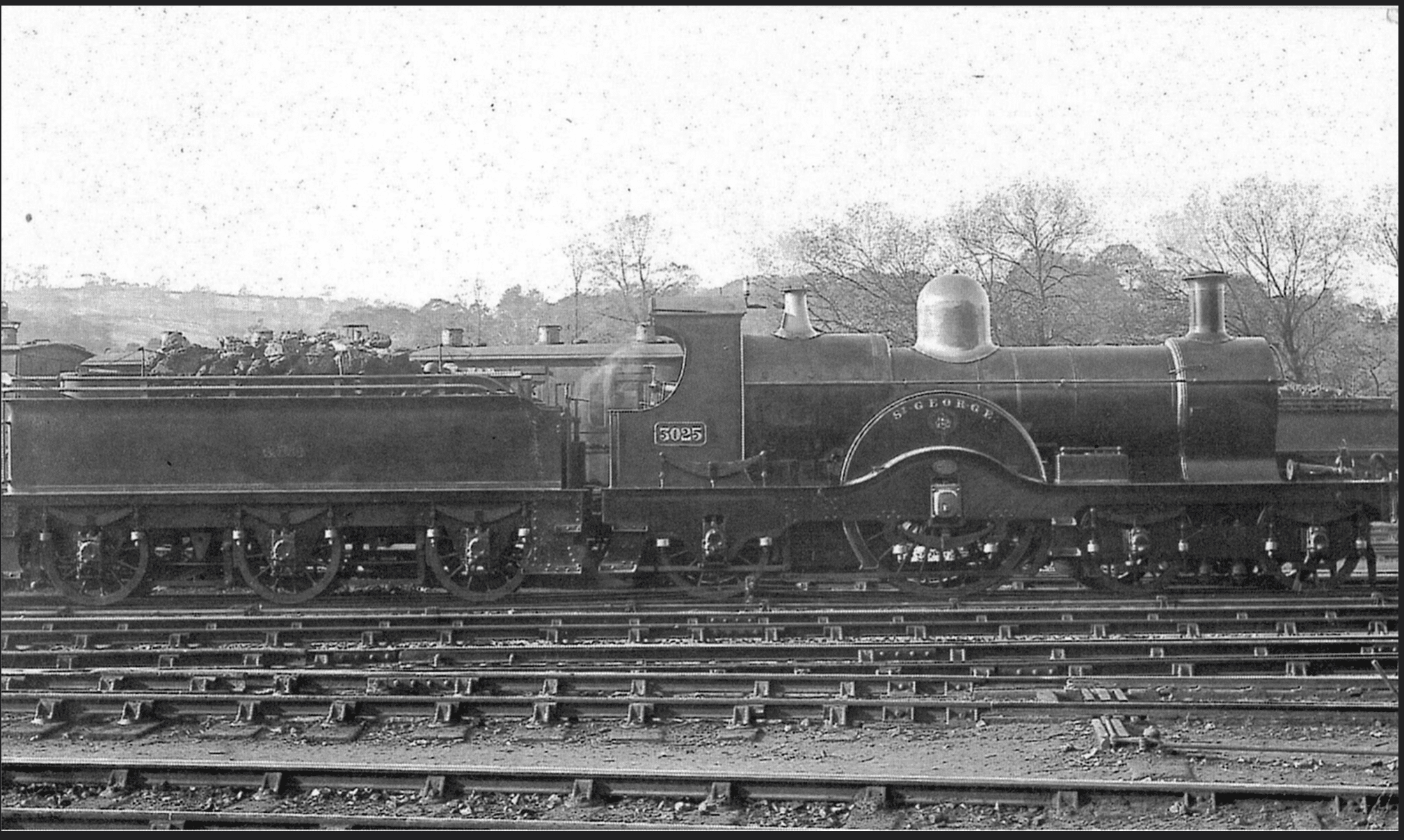

However, there were two GWR locomotives named “Saint George.” The first was number 3025 of the Achilles class, built in 1891 and decommissioned in 1908; the second was number 2923 of the “Saint” class, built in September 1907 and decommissioned in October 1934.

Of the two Saints George, it is the latter — 2923, active from 1907-1934 — that seems more likely to be associated with this pan, but I am still not confident of this connection. It is odd to me that a railway pan would be stamped for a locomotive and not for a kitchen car. I also do not know if 2923 was assigned to a Pullman route during this period, and while there is an impressive quantity of British Rail and Pullman archival data online, I haven’t yet found the rail schedules that would confirm this. If you feel like joining me in this research, I would welcome the company, but bring your space suit — this rabbit hole has taken me straight down through planet Earth and out the other side and now I think I’m floating out in space somewhere near Jupiter.

But back to Earth! Hitching all these stamps together (so to speak), we think this pan was made in the mid- to late 1920s by Smith & Matthews for service starting in 1929 on a luxury Pullman line of the Great Western Railway. It may have been stamped for locomotive 2923, “Saint George,” which was active from 1907 to 1934. After 1931, GWR ended Pullman service and the pan may have gone to the Southern Railway or perhaps stayed with GWR for its other luxury dining trains.

World War II interrupted most passenger train service in England (and all Pullman service), and after the war GWR, Southern Railway, and the Pullman Car Company were all nationalized into British Rail. The BHTS stamp indicates that this pan continued working into the 1950s at least. It’s impossible to say for how long the pan was active before its retirement, but if it entered service circa 1929 and survived to pick up a BHTS stamp in 1953, its career spanned at least 24 years.

What a pleasure it is so see this pot so lovingly restored and still in use almost a century after its manufacture. I’d like to thank Martin for sharing this pan with us, and for his beautiful photographs that really bring it to life.

As always, I’d love to hear from railway fans (and copper collectors!) who could help substantiate or dispute our theories as to when this pan was made and where it saw service. Smith & Matthews pans are few and far between and the history of the company is only sparsely documented — and it’s a real possibility that these pieces are actually Benham make. Please leave a comment if you can contribute to the discussion!

Such a wonderful “survivor” with interesting history! This pan is a gem! Thanks for sharing!

“beautifully organic disorganization, like weathered tree bark” – what a lovely turn of phrase, poetic imagery. When will you write that book! Kickstarter this, and I’ll be first in line.

Thank you William — I guess copper brings out my inner poet!

VFC wurde noch internationaler – nun mit Übersetzungsfunktion in vielen Sprachen. Großartig!

VFC became even more international – now with translation function in many languages. Great!

VFC est devenu encore plus international – maintenant avec une fonction de traduction dans de nombreuses langues. Génial!

Thank you, Martin! A reader wrote me to inquire about the demise of the translation function. I’d made some changes to the site a few months ago and lost that feature. I’ve found a replacement — it’s based on Google’s automated service, so my apologies in advance if there are some odd word choices! There are many more languages available, so please let me know if there are others you’d like to see offered.

William, when I was allowed to read this post beforehand, I was enthusiastic about the same poetic formulation. VFC is really a talented writer and researcher. Despite all the advantages of the Internet, it would be really desirable if all these findings, which have been gathered over the years, were published in book form at some point. Hands-on books are something completely different.

VFC, I have one unmarked pan with the classic English arrow shape handle in bronze, matching lid, so unusual but they do exist.