As owner Matt puts it, “My expectations were massively exceeded.”

| Type | Tin-lined Windsor in hammered finish with iron handle fastened by three copper rivets |

| French description | Sauteuse évasée martelée et étamée avec queue fer munie de trois rivets en cuivre |

| Dimensions | 15.9cm diameter at rim by 6.4cm tall (6.3 by 2.5 inches) |

| Thickness | 2.6mm at rim, likely thicker in base |

| Weight | 1484g |

| Stampings | None |

| Maker and age estimate | Unknown; 1850s-1880s? |

| Source | eBay |

| Owner | Matt M. |

This little pan has become a favorite of its owner Matt M., and part of the pleasure is his feeling of having found a special piece. “I saw this little gem and had to get it,” he told me. “The pictures on eBay were not very good but the price was right. My expectations were massively exceeded.” (I’m sure the beautiful polish and tinning job by Rocky Mountain Retinning helped!)

A sauteuse évasée — also called a Windsor — has a flared shape specialized for the reduction of sauces by maximizing the surface area exposed to the air. But there is a second, more subtle effect going on: the geometry ensures that the ratio of surface area to volume remains steady. What this means is that as water evaporates out of the sauce and the level drops, the pan narrows and the exposed surface area gets a little smaller too. This may sound counterproductive for the whole sauce-reducing process, but it actually works in your favor: the rate of evaporation slows down as the sauce concentrates. If, like me, you’ve ever yelped in dismay to find your balsamic reduction has turned gluey while your back was turned, you might try a Windsor next time as it’ll start putting on the brakes before you burn things.

This is a petite one, just under 16 centimeters (6.3 inches) at the rim tapering to 12cm (4.7 inches) at the base. You could fit the base of this pan in the palm of your hand, but the flared shape means it can hold more than a saucepan with the same footprint. Larger Windsors with more floor space can even step in as sauté pans, which is why this kind of pan is sometimes called a fait tout — “does everything.” (That said, I see pans ranging from from cocottes to stewpots to stockpots sometimes also called faits tout, perhaps reflecting the loosening of the French strictures around pans kept for specific purposes.)

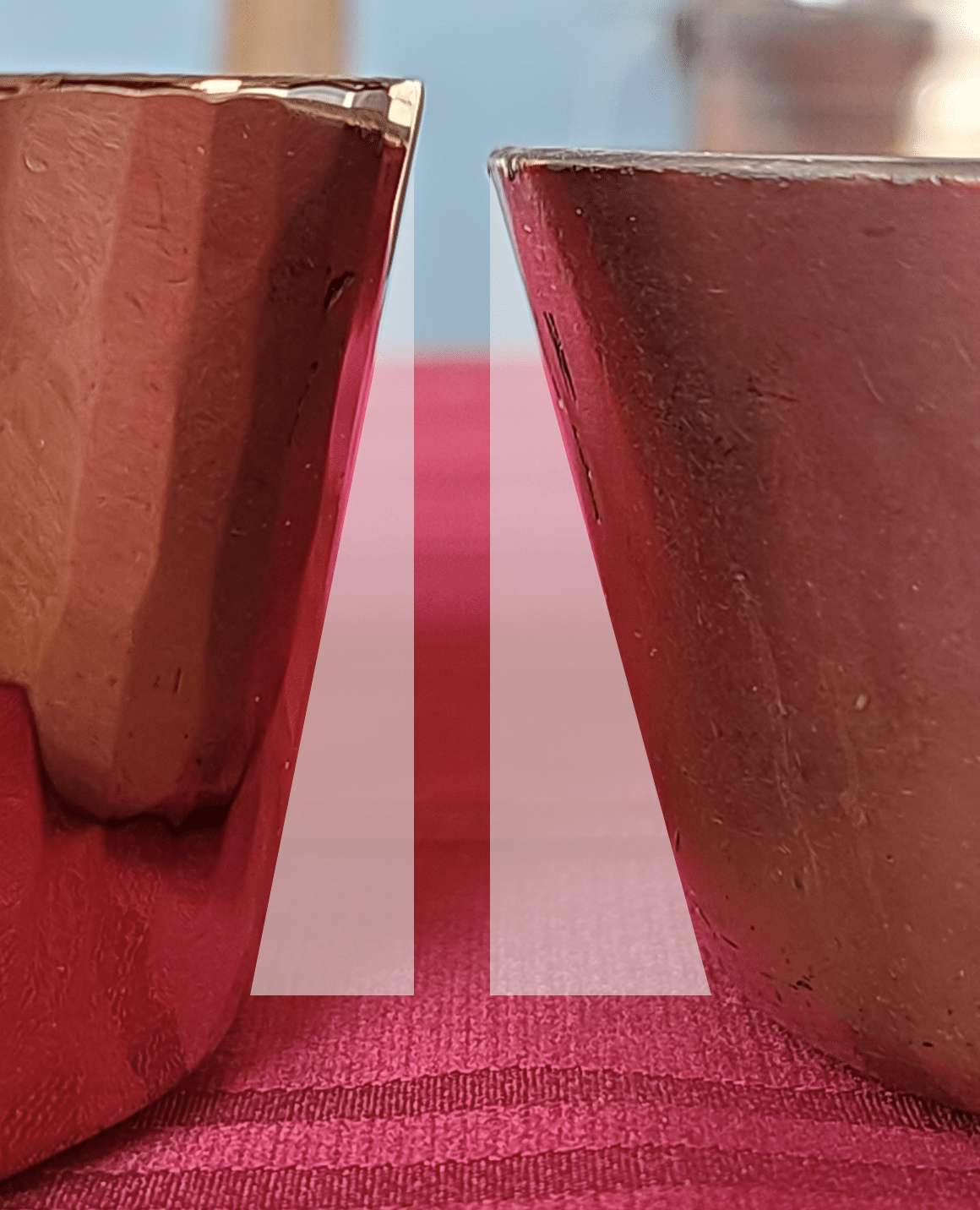

But this pan has unusual geometry in that its sides are quite steep. In the photos below, the pan on the left is this shiny hammered Windsor, and on the right is a Peter Brux Windsor of the same diameter. The second photo is overlaid with triangles lined up with each pan’s sidewall. The triangles are the same height, but as you can see, the triangle on the left is skinnier than the one on the right. The sidewalls of this hammered Windsor are at a steeper angle than a “normal” Windsor.

Another unusual element of this pan is its construction.

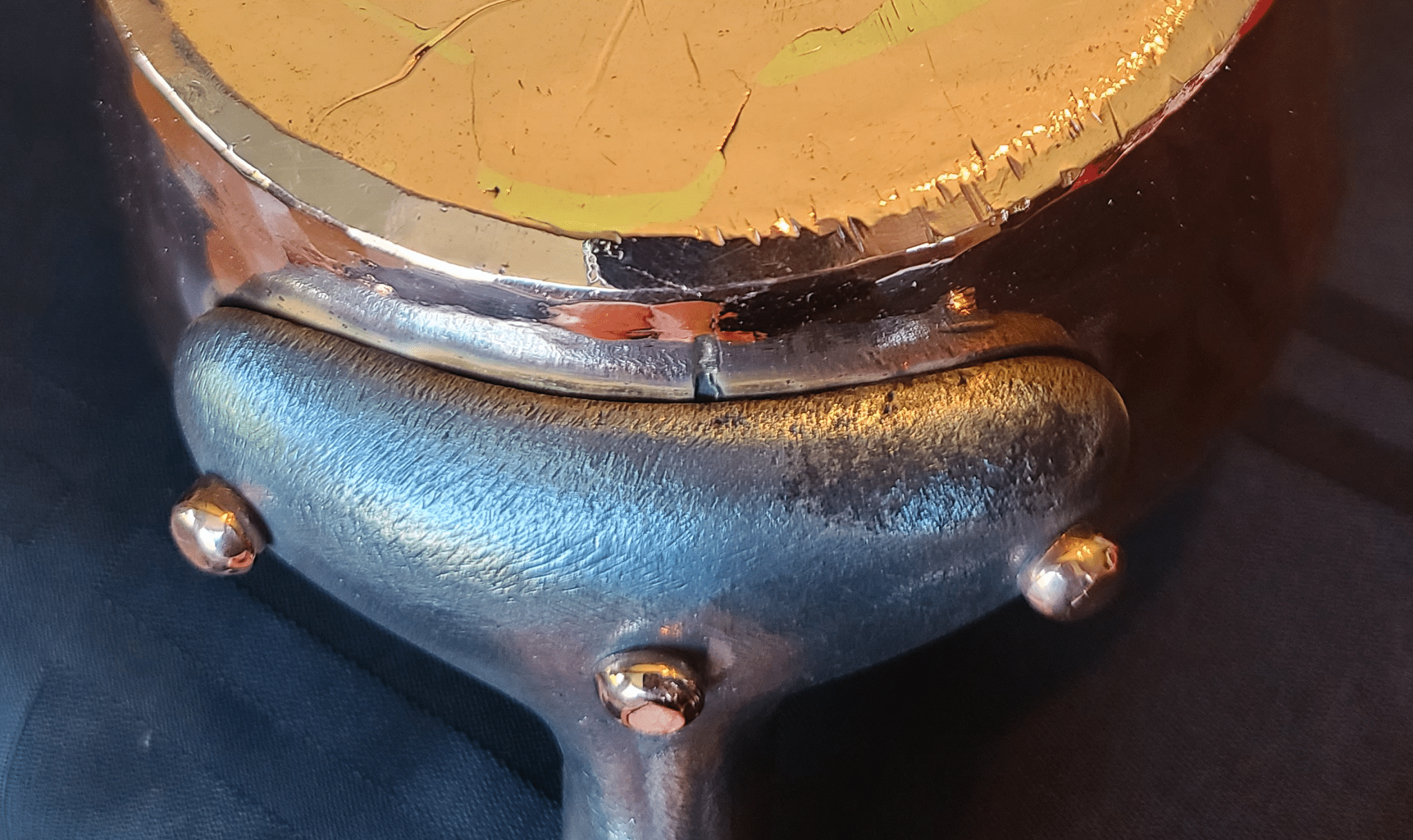

Yep, those are dovetails. I think this is the first dovetailed Windsor I’ve seen. I’m sure there must be more out there, but based on my experience — or rather, lack of experience — I think they’re pretty rare. Most Windsors are hand-raised from a flat sheet or spun on a lathe, and I can’t see an obvious reason why this one had to be dovetailed instead. But the work is beautiful. The four large crenellations are perfectly aligned like the points of a compass. (And speaking of compass — albeit of a different sort — you can spot the dot in the center of the base. This is the mark left by the smith’s compass as he swept the circle he would cut for the base piece.) As is often the case with dovetailed pieces, the handle is placed over the sidewall dovetail — the bottom of that seam looks to have become slightly separated but has been repaired with brass.

This pan has been made with care and skill. The base is beveled to give the edge an extra work-hardened plane to help resist dings.

The rivets are large and flush-set on the interior, and small and rounded on the exterior. You can more clearly see the sidewall dovetail on the inside of the pan.

The handle is cast iron that has been filed all over at a consistent angle, giving it a lovely even texture. “The handle has a beautiful ergonomic feel, which I find on some of my J. Gaillard pans,” says Matt. “It is not perfectly straight, and so I imagine it was hand worked. It is quite thick but has a noticeably flat top. It just feels as if the person putting it together was conscious of a ‘comfortable feel.'”

“The construction and unique side angle leads me to believe that this is late 1800s to early 1900s,” Matt adds. I suspect it’s a little earlier than that, possibly 1850 to 1880. I’d love to hear what you think as well.

“I’ve never seen a pan like this and am super happy to own it,” says Matt. I heartily agree that this is a special piece and I’d like to thank Matt for sharing these photos and his impressions of it.

Had I discovered this little exotic in Europe, I couldn’t have resisted buying it. Something special again – the striking hammer pattern, the old handicraft technology, the lovingly reworked handle. A little gem!

My opinion on the technical terms used in sales ads:

Some of the sellers are not sufficiently knowledgeable to know the appropriate terms. Some terms are meanwhile used inflationarily and no longer differentiate the designs and the intended use, such as “pan” or in French “casserole”. Still other sellers use multiple terms in the heading of their offer to attract more attention. They use terms like tags. So one should not take these terms too seriously. Finally, one can orientate oneself with VFC “useful terms” and “buyer’s guide”.

Most curious, never seen one like that. It would seem an unnecessarily difficult way to make that shape. Imagine the long curved strip of copper to make the walls. Could it be the first Windsor the coppersmith had made? The chunky cast handle looks 20th century.

It does beg the question – when did this shape first come about? I often read the phrase “traditional French batterie de cuisine ” and I wonder exactly what that means. The closed range was invented at the end of the 18th century and probably became widespread by the 1820’s so flat bottom pans post date this. Early copper was either hand raised, lockseam or possibly riveted and tends to be simple spherical or cylindrical shapes.

Anything with cramp seams is likely to be post 1850 and industrial techniques after 1880. Some designs we know are 20th century. I don’t think I have seen a Windsor pan that I could be sure was much before 1900 in date and this may be the earliest example.

It would be interesting to list the various shapes and put the date of the first mention we can find for each in a catalogue, cook book or manual.

Hello Copper Lovers !

This is what I call a faceted pot. It is between “fort” and “extra-fort” copper model.

We can find at the base sometimes 2, sometimes 3 facets (facettes, chanfreins ou arêtes in french if you prefer). Usually they are “extra-fort” and “sur-extra-fort” pots (but I have already received a 2mm “fort” copper series with 2 facets, very rare).

The best copper pots you can find on the internet are often simple “extra-fort”.

The best, which are almost impossible to find and I know few people who have them, are in order

:

the “extra-fort” with a reinforced base, the “sur-extra-fort”, the “sur-extra-fort” with a reinforced base and, finally, the non-standard ones (up to 6mm thick, absolutely rare).

Today’s term “extra-fort” is almost a joke from the manufacturers.

The pot of this article falls between the “fort” and “extra-fort” category of the old time. I let you imagine the “extra-fort” model and the “sur-extra-fort” model, without counting those with reinforced bottom!

I gave the name of facets because in general they are made of a copper which is very beautiful. When the pots are well polished, especially if they are hammered, they sparkle like diamonds!

You can find it at GAILLARD, JACQUOTOT, LEGRY and many others.

The faceted models are above on “saucepans-casseroles”, “sauté pans-sauteuses”, “flared sauté pans-windsor-sauteuse évasée”, “bain-maries”.

Most of the time, they are not mounted in dovetails (I use that term, although it is wrong, because everyone seems to have adopted the name. They are more angular incisions). But sometimes, like in the example of this pot, they are dovetailed.

Almost all of the faceted pots I have received are from after 1900, including the dovetail ones.

For the names of copper pots in French, it’s tricky.

Depending on the period, the authors (books of Carême, Gouffé, Escoffier …), we can find different names given to the same pot.

For example, for me, this pot is a “flared sauté pan-sauteuse évasée”. But some will simply say “sauteuse”, “sautoir” and more rarely a “coupe du midi”.

This type of curved pot has probably been around for as long as the “casserole ordinaire-saucepan”.

By the way, speaking of an ordinary saucepan, we find in some dictionaries of the 1930s, a definition which indicates that the ordinary saucepan is called a “russe”.

Which is wrong.

I recall that an ordinary saucepan has a height equal to about half the diameter while a “russe” has a height equal to about 2/3 the diameter.

Even today, in many restaurant kitchens, we say a “russe” for an ordinary casserole. It is quite astonishing to see that this error has become normal. But at the same time, nobody has been making real “russe” casseroles for a long time!

And it wouldn’t be surprising if in the 1930s no one had been making them for quite some time.

Last point, people in France, individuals, do not bother with all the names of kitchen pots.

For :

the saucepan or flared saucepan: la casserole

Sauté pan: la sauteuse

The fryng pans: la poêle

Stock pots, stew pots, stew pan, braising pan, Le Creuset cast iron: la marmite

The pressure cooker, the tall oval pots: la cocotte

Everything that goes in the oven: le plat à four. It is designated by its shape and material or color. We will say “donnez-moi le plat à four carré en cuivre, le plat à four en terre, le large plat à four, le petit plat à four, le plat à four avec les poignées, le plat à four avec le couvercle, le plat à four blanc…

“give me the square copper dish, the earthenware round, the large one, the small one, the one with the handles, the one with the lid, the one white…. etc …

Either way, I really like the copper pot in this article and congratulations on finding it!

Cook great food in it, for you, your family, your friends!

Regards, T.J.

TJ, thanks for the informative comment — you always give me a lot to think about! To be honest I am ambivalent about using the term “Windsor” for these pans — it is so common but seems a strange convention. I have been trying to figure out what the origin of the term is but have found nothing. Do you happen to know where the name came from?

I think it might help narrow it down if we knew what length of time the slant-sided pans have been known as Windsor. Finding out (approximately) what year a nickname comes from can often hint at the reason as well. For example, there’s a wide slant-sided knot for neckties known as Windsor, and the pan shape could conceivably be named for the shape of that knot – but only if the pan name is from 1936 or later, since there was no wide-tie-wearing Duke of Windsor until then. And if the pans mysteriously began to be called Windsor in about the late 30s – early 40s, we can probably tentatively call “Bingo”.

There are so many possibilities: was there perhaps a famous hotel or restaurant named Windsor involved?

The royal House of Windsor has had that name since 1917, so if it’s to do with royalty it couldn’t be before then (though it could be after, especially at any time when the name was in the news more than usual, see above).

You could also name your pans Windsor, Harris, and Uxbridge, your funnel Vivian, your knife Iverson, your spoon Pelham, and your carving fork Yancey, using the initial letter to indicate the shape in each case. Russians could call their whisk Фёдор and their food processor Жега́лкин. 🙂

I would love to know it, too. I can’t figure out where the term came from. After spinning my wheels on it for quite some time, I went so far as to use the “Ask a Librarian” service of the U.S. Library of Congress to see if a reference librarian would have better luck. Believe it or not, they came up empty handed as well. If anyone out there knows the answer I’d be grateful for the help!

It’s not impossible that the name “Windsor” for a pan could be a term that was propagated by only a tiny minority for only a short time, highly obscure to begin with and now unrecognized by anyone outside this small circle.

The name “Windsor” will probably remain a mystery for a very long time, if not forever. We all know buzzwords (vogue terms) that appear out of nowhere and are suddenly on everyone’s lips. “Windsor” also seems to be in international use now. This made it possible to identify corresponding pans without the need to translate the description of the pan shape. The first letter W already reminds of this shape. Nevertheless, I hope that at some point there will be a more profound clarification of the origin of this “technical term”.