The swing handles are just one unusual element of this pre-war stewpot.

| Type | Tin-lined stewpot with brass swing handles and fitted lid |

| French description | Bassine à ragoût étamée et martelée avec anses pivotantes en bronze et couvercle a degré |

| Dimensions | 36cm diameter by 17.5cm tall (14.2 by 6.9 inches) |

| Thickness | 2.8mm at rim |

| Weight | 8854g (19.5 lbs) pot only; 11430g (25.2 lbs) with lid |

| Stampings | E. Dehillerin 18 Rue Coquillière; Cite Universitaire M-I Paris; CU |

| Maker and age estimate | Possibly Dehillerin, or Villedieu; 1930s? |

| Source | FrenchAntiquity (Etsy) |

This is a lovely example of institutional copper that has survived in remarkably fine form. I have come to consider pieces over 30cm diameter to be restaurant-scale, and this one, at 36cm (14.2 inches), is squarely in that category. It measures 2.8mm at the rim, making it just about restaurant-grade thickness as well — 3mm is where I lay the boundary between consumer grade and professional grade. But of the stewpots I’ve measured, none over 30cm diameter exceeds 3mm thickness (and you know I look for the thickest ones I can find). Perhaps stewpots are like stockpots — over a certain diameter, additional mass of copper offers diminishing returns. By weight this piece lines up neatly between my 34cm (3mm, 8404g) and my 40cm (2.6mm, 9190g) stewpots, so I assess it is likely 2.8mm throughout.

This is a lovely example of institutional copper that has survived in remarkably fine form. I have come to consider pieces over 30cm diameter to be restaurant-scale, and this one, at 36cm (14.2 inches), is squarely in that category. It measures 2.8mm at the rim, making it just about restaurant-grade thickness as well — 3mm is where I lay the boundary between consumer grade and professional grade. But of the stewpots I’ve measured, none over 30cm diameter exceeds 3mm thickness (and you know I look for the thickest ones I can find). Perhaps stewpots are like stockpots — over a certain diameter, additional mass of copper offers diminishing returns. By weight this piece lines up neatly between my 34cm (3mm, 8404g) and my 40cm (2.6mm, 9190g) stewpots, so I assess it is likely 2.8mm throughout.

Its owner stamp marks it as part of the batterie de cuisine of a Paris university in the 1930s — more on that history later — and the surface of the copper is uniformly covered with the short sharp scratches that speak to me of daily use in a busy kitchen.

And I think it’s beautiful. It came fully restored from Steve Nash at FrenchAntiquity, and whoever his magic tinner is, he or she does a wonderful job. This pot has been well restored but not excessively so, in my opinion. I am reminded of my misadventure a while back in which an overzealous local retinner polished away the bumps and wrinkles from an early Windsor (extending to obliterating its Gaillard stamp). Of course, copper collecting is a matter of personal taste and each of us should have our pieces look and feel the way we want them to, but once a pot’s surface character is polished away it is gone forever. One of the reasons why I appreciate Steve Nash so much is that his aesthetic for antique copper is in line with my own, and he offers pieces like this one that has been made to look its best while retaining its experience and character.

In addition, I see traces of residue around the handle brackets and in some of the deeper pockmarks, which suggests to me that it has not been immersed in caustic. A caustic soak is a lengthy deep-cleaning technique to get at dirt and grime in all the nooks and crannies. Don’t get me wrong, caustics are sometimes the only way to lift oxidized grease and burned oil residue — I have sent pots off to restoration that were so encrusted with grime that aggressive chemical treatment was the only remedy — but I can usually spot a piece given this treatment by the squeaky-clean “naked” look of the copper.

But to my eye, dissolving every fleck of grime from every scratch and ding flattens the appearance of the copper, and for some antique pieces, can produce an anachronistically perfect appearance. In my experience, a good retinner will consider the entire piece and will resort to aggressive techniques (like caustic soaks, heavy polishing, and so forth) only when necessary to remove deposits and preserve the piece. Less aggressive techniques may be more time consuming, but in my opinion may be more appropriate for antique pieces because they result in better congruence between the age and history of the piece and its present-day condition.

As above, Steve’s retinner has not been overly aggressive with this piece and it comes to me with a pleasing balance of cleanliness around the handles and across the base while retaining the surface character that expresses its era.

It is fitted with brass swing handles of a type I’ve never seen before on a pot like this.

The handgrip is a massive piece of brass threaded into brackets attached to the body of the pot with two large flattened rivets.

These swing handles are an unusual choice for this piece and this remains the only large stewpot I’ve seen with handles like this. They are quite space efficient — they project no more than a few centimeters from the body of the pot — but the experience of using them is subtly different than with fixed handles. When I lift the pot there is a moment of slack before the handgrip engages the brackets, but once settled, the handles feel firm and reliable. Whereas a fixed handle engages the body of the pot across three rivets, these wide-set brackets spread torque across four rivets spanning a greater section of the pot’s circumference. I found a feeling of firm connection between my hands and the pot that I don’t always feel with fixed handles with their narrow-set prongs.

So why don’t we see more swing handles? I think the answer may lie in the complexity of their manufacture. Making each of these handles required threading a handgrip into each bracket and holding everything in place for riveting. Think about it: do you drill the rivet holes in the pot first, and then size the handgrip to space the brackets correctly? Or do you make the handgrip and brackets, place them on the pot, and then drill the rivet holes to match? Compare this conundrum to the straightforward wham-bam-thank-you-ma’am process of attaching one-piece handles: they’re all cast to the same mold and so the rivet holes are at exact pre-determined locations. You can pre-drill the pans, pre-drill the handles, and they all fit together just fine.

I’d be interested in reader opinions about this: Have you seen large heavy pieces like this one with swing handles? Why aren’t they more common?

This stewpot comes with a lid with matching stamps that I believe to be original. It’s a beast at 2576g — more that 5½ pounds. It is beautifully made: the drop from rim to the inset is deep enough to settle neatly and create a good seal. The handle is brass with two rivets on each bracket and the brass shows fine scratch marks from post-cast finishing. Both of these are indicators of quality: later 20th century pieces devolved to one rivet per bracket and appear to have received only cursory hand-finishing (if any attention at all). There is a large dot in the center of the upper surface of the lid, which suggests this could have been a hand-cut piece of copper.

Or rather, the lid would create a nice seal if the rim hadn’t been deformed a bit. In the photo below you can see how there is a bit of a gape between lid and pot in one area. The rim of the lid looks slightly distorted, but the primary culprit to my eye is that the rim itself has been deformed. In the detail photo on the right you can see that the edge of the rim has spread and then smoothed back down.

I think this is from years and years of cooks rapping spoons against the edge of the pot! I took a careful look and made a note of the areas around the rim where the flattening occurs. As you can see in the photo at right, if you set the pot down with handles on either side — as would be natural when placing it on the cooktop — the deformed areas (marked with the curved lines) are at top and bottom. This is exactly where I would knock my spoon against the rim to remove traces of sauce!

I think this is from years and years of cooks rapping spoons against the edge of the pot! I took a careful look and made a note of the areas around the rim where the flattening occurs. As you can see in the photo at right, if you set the pot down with handles on either side — as would be natural when placing it on the cooktop — the deformed areas (marked with the curved lines) are at top and bottom. This is exactly where I would knock my spoon against the rim to remove traces of sauce!

(I have read advice for cooking with copper that scolds against this practice, but it is so sensible and ingrained that I don’t beat myself up for doing it. Rather, I focus on using kitchen implements that are less likely to damage the copper. I have plenty of antique pieces with rims like this criss-crossed with what look like hash marks, and I suspect these were left by the hard edges of the shaft of an inexpensive pressed-steel cooking spoon. If you’re going to knock a spoon against the rim of a tinned copper pot, like I do pretty much every time I cook, I suggest you reach for wood, plastic, or silicone tools. For my part, I’ve removed metal implements completely from my cooktop area so I don’t even have to worry about it.)

Another interesting feature of this piece is that it is dovetailed (more correctly, joined with cramp seams). The base has wide-set crenellations all around the circumference and the sidewall has a vertical seam showing where the two pieces of copper were joined with brass braze. As is conventional, one of the handles is set to span the join, just as we see with one-piece fixed handles.

When we turn to look at the piece’s stamps — as we will do now — I will explain why the dovetailing caught my eye.

This piece carries both owner’s and maker’s marks. The pot and lid both carry the same E. Dehillerin stamp, the “oval with dots” version that I have tentatively — quite tentatively — placed in the 1900s-1940s. This version of the stamp should have a full oval line around it but the strikes on this pot and its lid show only segments of the complete outline. Of interest, the segments (and other fine details) are almost exactly the same across both strikes, which suggests to me that the same nearly-worn-out physical stamp was used on both pot and lid.

The other stamps are owner’s marks. Pot and lid are stamped “Cite Universitaire M-I Paris” and the pot carries an additional plain “CU”.

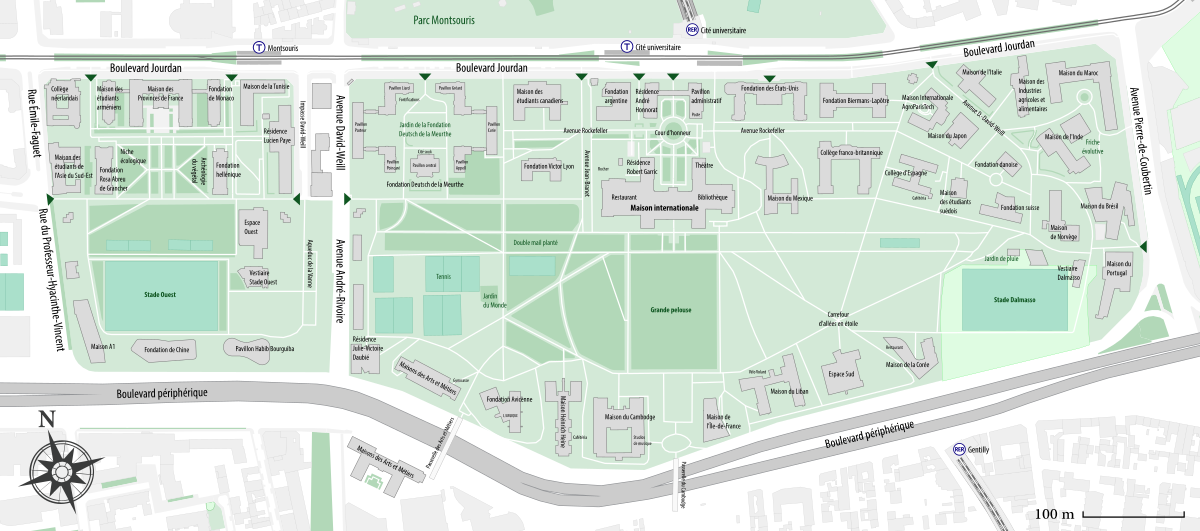

I believe these stamps represent the Maison Internationale of the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris. This sprawling complex of buildings — the “international university city” — was begun in the 1920s to attract and house students from all over the world as a countermeasure against the national hostilities that provoked World War I. This article from the literary site Purple captures the idealistic sentiments of that moment in a way I find particularly evocative:

We should begin by noting that by 1918, France had lost a third of its student population to World War I. The war had been a massacre, a descent into absurdity that would traumatize the country forever after. From it, the writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline would spin one of the greatest books in French literature, Journey to the End of the Night, and many men and women — intellectuals, scientists, and businesspeople alike — would try to find ways to prevent anything of the sort from ever happening again. In 1919, France’s minister of education, André Honnorat, introduced an initiative to create campuses for both French and foreign students. The aim was to contribute to international peace by building a place where the world’s youth could learn to live together. Thanks to the help of generous philanthropists like the industrialist Émile Deutsch de la Meurthe, the first cornerstone was laid in 1925. Since then, three major construction phases have produced a total of 40 residences, each representing a different country and funded through a combination of sponsorships and subsidies.

The Cité Internationale Universitaire (CIUP) thrives to this day at the southern edge of the 14th arrondissement, confined by the ring road around Paris.

The Maison Internationale is the centerpiece of the campus, an “international house” for all students to gather to eat, study, and socialize. It was built with a grant from John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and designed by the American architect Jean-Frédéric Larson. Rockefeller had previously donated funds for the restoration of Versailles and the chateau Fontainebleau, and the new Maison Internationale was intentionally designed in the same style. Construction began in 1933 and was completed in 1936 — ironically, in the lead-up to the Second World War. During the war, this “city of peace” was occupied by the Germans and then by the Americans, and like so many edifices in France, it suffered at the hands of both. In the 1950s, the French government raised funds to repair, restore, and expand the Cité and more buildings were constructed to showcase the new era of peace.

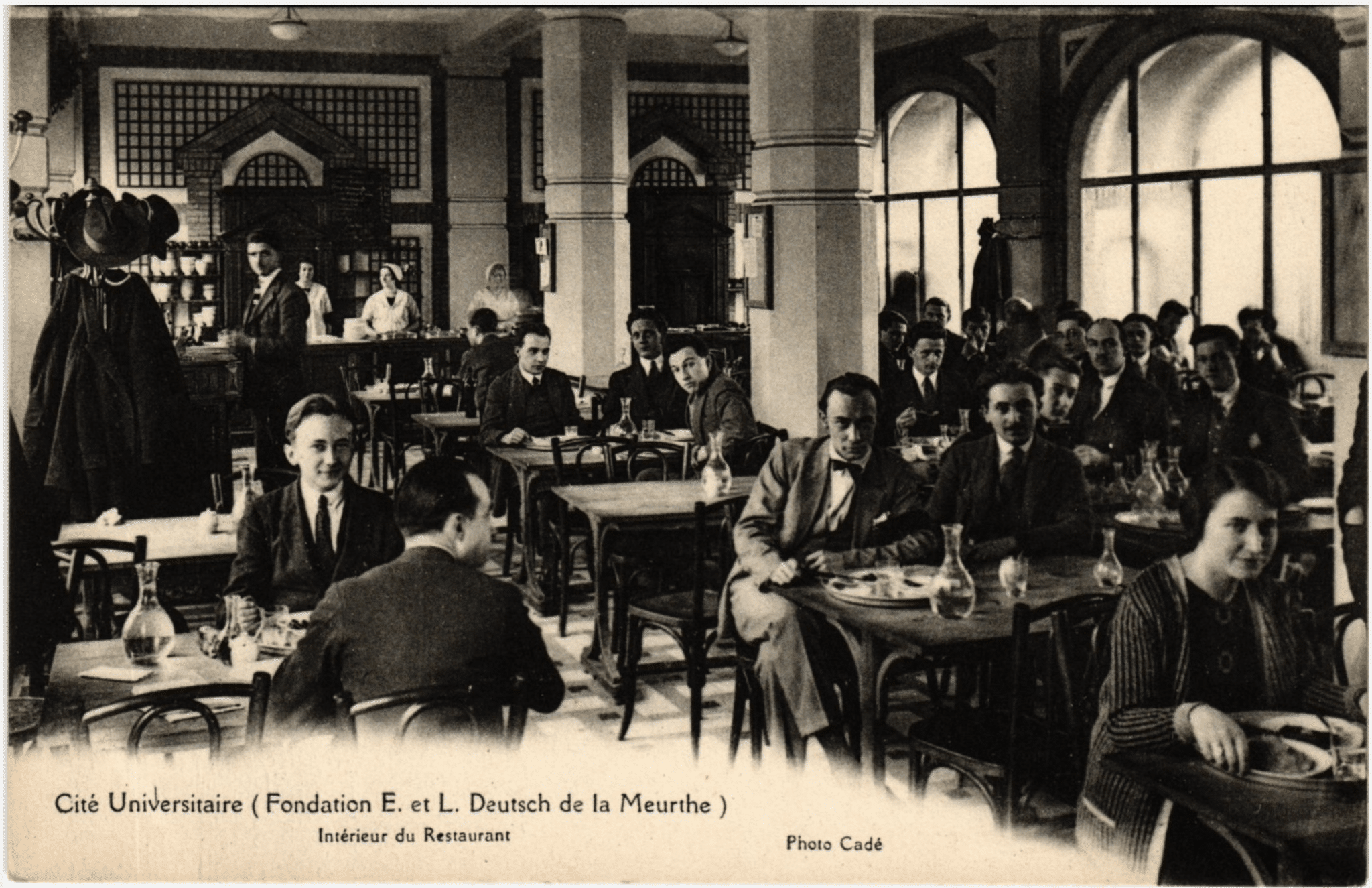

The restaurant of the Maison Internationale occupies the ground floor of the west wing of the building. In photos of the north-facing main facade of the building (such as the one below at left), the west wing is on the right. The restaurant spans the ground floor and its large arched windows offer views to the north and south. It was never a fancy restaurant but rather a cafeteria for students to gather and eat together. The period photo below on the right captures a busy lunchtime. If you use Google Maps’ Streetview function, you can walk around inside the restaurant in the present day and almost recreate this view, now bright and utilitarian in the 21st century style but with the same pillars and arched windows and perhaps echoing with the same bustle and chatter almost a hundred years later.

That’s the kitchen that I believe used this pot. I can forgive a little spoon-rapping in that environment.

As a final note, I’d like to return to the dovetailing. If this stewpot was purchased new for the restaurant at the Maison Internationale circa 1933-1936, then this is quite late to see a hand-joined piece. My research on the advent of mechanization in the first decades of the 20th century suggests that dovetailing was largely supplanted by deep-drawing or lathe-spinning by the 1920s. Among the factors at play were rapid advances in mechanized metallurgy and metalworking for armaments for WWI, the death of thousands of skilled craftsmen during the war, and the surge of young men to replace them — too young to serve in the war — with no older men to train them in the traditional techniques. (Casualty figures for WWI estimate 1.6 million French soldiers died, between 4.3-4.4% of the population at the time).

The physical qualities of this piece — the dovetails, the twin-riveted lid handle brackets, the hand-finishing, the dot, the complex handles — represent 19th century craftsmanship. But to the best of my knowledge, the stamps are 20th century. Dehillerin began as a chaudronnerie but by the early 1900s demand had outstripped its production capacity and it was already reselling a mix of its own work alongside pieces from Villedieu; consequently, the Dehillerin stamp on this piece is not an affirmative indicator that it was made by Dehillerin in Paris. But by the 1920s, judging from the work I see for Jacquotot and Gaillard, the Villedieu makers were cranking out seamless deep-drawn pieces left and right.

One possibility is that this is an earlier piece — that is, late 1890s into early 1910s, when the transition from dovetailing to deep-drawing was not complete. Another possibility is that this was a custom piece, a one-off with unusual handles. Would it have been easier to throw together a piece like this by hand than to commission it from one of the busy mechanized chaudronneries? Readers of this site know I am prone to flights of fancy — rather than spin another tale, I’d like to ask for your thoughts. What do you think is a reasonable explanation?

References

The quote from the article on Purple is taken from this lovely writeup of the author’s visit in 2016.

World War I casualties as a percentage of population: https://brilliantmaps.com/ww1-casualties/

When I saw this stew pot on Etsy a long time ago, I was immediately intrigued. Above all, I was excited by its origin and the ideals associated with the founding of this international university. The unusual folding handles and other features of craftsmanship, had also attracted me. As is often the case, ideals were ultimately sacrificed to pragmatic considerations. I couldn’t see an appropriate place for this beautiful pot, nor a use for it. So I passed. It is comforting that I now know it is in the very best hands at VFC.

I believe that there probably was an extra cost in having this custom handle applied to an already expensive stewpan. What significant benefit would this type of handle give to the pan that would justify an extra cost? Another vintage copper pan mystery!

As far as I know, folding handles (swinging handles; in German “Klappgriffe”) are most often found on pans used mainly in the oven (especially roasting pans). Space is definitely limited there, while on the stove you can always create some space and get out of the way.

Seeing vintage French stewpans and rondeaus listed for the past few years on ebay, Etsy and leboncoin it appears that the major restaurants, estates and commercial workplaces had no problem buying the standard configuration for these pans to be used in their ovens. It still seems strange to me why Cite Universitaire would need to order this custom style for their kitchen.

It is true that the vast majority of pans had “normal” handles. But I also know numerous pans that were equipped with these drop handles as standard. Even today’s manufacturers have this kind of handles in their offer. By the way, many tool boxes are also equipped with drop handles. Probably to be able to store them in a space-saving way. In the Schwabenland catalog, these handles are also called “Fallgriffe” (drop handles). Schwabenland mentions at one point in the catalog the low ovens that were common at the time (at least in Germany), and also uses this to justify the advantages of their nearly horizontal stick handles on saucepans.

You can also see this type of drop handles in the Gaillard and Dehillerin catalogs. Or even fixed handles pointing vertically upward to save space. My roasting pan for the oven also has handles like this. Some sauce pans that were meant for bain maries have very small handles. As you can see, there were different solutions to gain space and very different needs of the customers, which the manufacturers met.

In the Schwabenland catalog, I just saw a double-walled beater kettle made of tin-plated sheet steel with cast handles (fixed), which was quite unusual for me. Water could be poured into the space in between, which prevented the whipping and stirring masses from burning. Thus a variant of a bain marie, this time for cooling.

In the high-end sector, regardless of the product group, there were and are always individual wishes and solutions. Who knows which ovens were in this Belgian kitchen and what the chef’s wishes were?

The top of the handles of a “standard” stewpan would probably lie a bit lower than the top rim of the pan so I don’t think the swing handles on this pan would have been necessary even if there were low ovens being used. I would think the original ovens have been replaced and the chef who ordered the pan has long since passed away so we can only speculate on whether this out-of-the-ordinary stewpan was bought because of necessity or simply because of personal preference of the chef.

As you say, Stephen, we can only guess, as we so often do. In the case of this pot, the height of the stove may indeed not have been a reason for this type of handle, since the handle of the lid determined the maximum height of stew pots. However, with some sauté pans and sauce pans, some of whose handles extend well above the corresponding lidded pans, the height of the stove may have played a role. However, I myself do not use these types of pans in my stove.

I further suspect that the width or depth of the stove was the deciding factor in saving a few inches by using these drop handles. At least, that was a deciding consideration in selecting my roasting pan with vertical handles. Mauviel’s modern versions also have these handles, which allow you to use larger roasting pans. My Dehillerin oval gratin pan (additionally stamped W.L) has ring handles, which are plainer but based on the same principle as drop handles. Another variant to save space in the oven. For kitchens in dining cars certainly an important criterion.

But, of course, I may be completely wrong with my speculations.

I would like to highlight other advantages of these drop handles. The handles are attached with 4 rivets instead of the usual 3. In case of impact, there is no risk that these handles break, as is not excluded with normal handles. We know corresponding repairs in pans presented here on VFC. The manufacture of these drop handles may have been somewhat more expensive, but should not have presented the craftsmen with any great challenges. The durability of these handles will have more than compensated for the extra cost. Perhaps this pot was transported more frequently over longer distances than usual. I think it is possible that it was brought from the kitchen to the refectory to ladle certain meals directly on site.